Anything but ‘The God Particle’

In science, an idiot's guide is just that

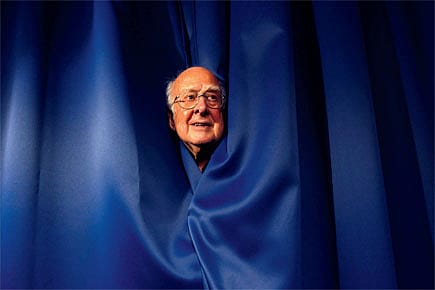

In retrospect, it is easy to say that finding the Higgs boson was inevitable. Peter Higgs has virtually been a household name ever since the Large Hadron Collider was first switched on nearly four years ago. Earlier this year, Peter Higgs was invited, as a special guest at a public lecture, to King's College London, the university at which both Higgs and I studied theoretical physics some fifty years apart. It was hardly a well publicised event—I was lucky to catch a glimpse of the solitary poster surrounded by internship notices and flat-share advertisements on a hallway notice board at King's.

The title of the lecture, 'From Maxwell to Higgs', delivered by Professor John Ellis, emphasises Higgs' stature, on par with the greatest physicist of the nineteenth century. In a wonderful opening speech, the 83-year-old Higgs spoke fondly about his time at King's College, his experience as the head of the Maxwell Society, and graciously acknowledged that he was one of many people whose work has contributed to the postulation of his eponymous particle.

The occasion was the birth anniversary of Einstein, whose theory of Special Relativity has been completely integrated with Quantum Mechanics under the banner of Quantum Field Theory (QFT). The discovery of the Higgs boson is the greatest discovery in QFT in over 40 years, and the first great scientific discovery of the millennium. The Higgs mechanism accounts for the existence of mass, a property of matter that is so inescapably a part of our experience of reality that even posing the question about its origin feels counter-intuitive.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

If the current trend in experiments in particle physics is anything to go by, then Peter Higgs may be the last theoretical physicist who lives to see a major prediction experimentally verified. The nature of theoretical physics is such that the gap between theory and experiment increases rapidly. Newtonian physics can be verified remarkably easily, as is demonstrated in schools everyday. Maxwell's electromagnetic theory can be verified by school-level experiments as well. By the time we reach Einstein's General Theory of Relativity, it takes observations made during solar eclipses, or of orbital trajectories of planets before it is confirmed. The electroweak theory of Salam,

Glashow and Weinberg was verified in a bubble chamber ten years after it was postulated. Higgs has had to wait for over 40 years. If direct experimental verification of a unified theory of quantum mechanics and general relativity is to be achieved using a particle collider, it will take an experiment at a practically unachievable energy level.

It is a shame that the Higgs boson picked up a colloquial moniker. On their own, neither 'Higgs' nor 'boson' has any linguistic association other than with the names of Peter Higgs and Satyendra Nath Bose. One ill-advised sensationalist book title, and the hitherto respectably named particle was suddenly the God particle. Of all the words that could have been associated with the particle, 'The God Particle' is surely the most dangerous, with its obvious pseudo-religious connotations. All it does is fan the flames of ignorance and half-truths that already plague the image of modern physics.

The fundamental problem is that QFT is described by the abstract mathematics of operators and algebra. There is a rigour and specificity in mathematics that spoken languages simply do not have. In physics, The Uncertainty Principle has an unambiguous mathematical form. Unfortunately, the word 'uncertainty' is ambiguous. This is one source of confusion and corruption. Danah Zohar, in The Quantum Self, makes a laughable, grotesque connection between physics and psychology misusing the term 'uncertainty': 'According to the Uncertainty Principle, the wave and particle descriptions of being preclude each other… The measuring conundrum for electrons is a bit like the dynamics of the primary interview in which, ideally, the psychiatrist would like to know both the relevant background facts and establish some sort of rapport with [his patient].' This is exactly the sort of dangerous pseudoscience that physicists have to deal with, a problem exacerbated by the 'God Particle' name.

One of the first things a young theoretical physics student must learn to cope with is the abandonment of the idea that the objects he deals with can be visualised. It is a monumental leap, and one that takes a great deal of effort. A particle is no longer a hard sphere that just happens to be too small to be seen because of inadequately powered microscopes. It is not a localised object. At the same time, it is not a smeared-out object either. To use an intentionally impenetrable yet specific phrase, a particle is represented as a momentum eigenstate of a quantum field. It is a completely different entity, a mathematical result.

The configuration of the solar system can be satisfactorily represented by a mechanical model using everyday objects like balls and balloons because the solar system is simply a scaled-up version of the model, governed approximately by the same Newtonian laws. Of course a black hole cannot be modelled in the same way because there is a whole new type of physics that governs black holes that is not appreciable in tennis balls and balloons. A model can only be used if the physics governing it is the same as the physics that governs the object being modelled.

Atoms, electrons, protons, quarks, photons and Higgs bosons are governed by the laws of quantum mechanics. Using everyday objects to illustrate the workings of the Higgs field is akin to representing calculus through the medium of dance. Alas, amidst the excitement of the greatest scientific discovery of our generation, there is no avoiding it. Graham Farmelo, in his splendid biography of Paul Dirac, The Strangest Man, describes the reaction in the press to the news of the first experimental verification of Einstein's General Theory of Relativity by Arthur Eddington: 'The pages of newspapers and magazines were replete with advertisements for scores of half baked accounts of Einstein's work churned out only months after the theory came to public attention.'

With the discovery of the Higgs boson, it is the turn of theoretical physics to suffer misrepresentation in the name of accessibility. The day after the announcement from CERN, the press agency Reuters made its winning contribution to the morass of bad descriptions of the Higgs field: 'Picture George Clooney (the particle) walking down a street with a gaggle of photographers (the Higgs field) clustered around him. An average guy on the same street (a photon) gets no attention from the paparazzi and gets on with his day. The Higgs particle is the signature of the field—an eyelash of one of the photographers.' Perhaps in a few years, the phrase 'photographer's eyelash' will exemplify bad popular science writing. One can only hope.

The most successful scientific theory of all time is also one of the least known and prosaically named. Very few museums have exhibits dedicated to The Standard Model, and most physics documentaries ignore QFT and treat quantum mechanics and special relativity as separate, unrelated entities. At a stretch, some of them name a few of the particles for the sake of completeness, but, by and large, it has stayed out of the public eye for the half-century that it has reigned. Now that the Standard Model has found one of its most sought-after particles, it will be harder to keep it out of the mainstream. In doing so, it will create the first major new challenge to science popularisers in the 21st century.