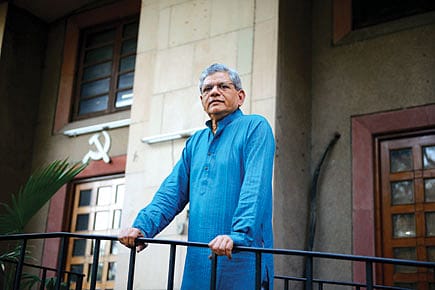

Sitaram Yechury: The Terminator

It was less than a year ago, in April 2015, soon after being elected the CPM's general secretary, that Sitaram Yechury had spoken to Open about his resolve not to let his party join any alliance before first strengthening it. His argument was that the Left had in the past successfully formed governments in Kerala and West Bengal on its own strength, and that was the key to a revival too. Ten months later, his position has swung the opposite way. He has lately been pushing for a tie-up with the Congress in Bengal. At the party's recent plenum held in Kolkata, that was the thrust of his statements. However, many believe that such a move is fraught with more danger than he has taken into account. A decision like this could determine his legacy as the CPM's top leader: whether the Left stays relevant or heads for political extinction.

In April-May, West Bengal and Kerala go to the polls. Other than tiny Tripura, these are the only two states where the Left has any significant presence. An understanding with the Congress in Bengal against Mamata Banerjee's Trinamool Congress, which rules the eastern state, could jeopardise its prospects in Kerala, where the CPM and Congress are the main contestants for power and thus bitter rivals. Yechury's proposal has created a divide within the party that will play itself out on 16 February, when the Politburo meets in Delhi, and on 17 and 18 February at a Central Committee meeting. "There is a lot of speculation over the tactics that the CPM will employ in the forthcoming elections to state assemblies," says Yechury. "Our electoral tactics will be in accordance with the Political- Tactical Line adopted at our 21st Party Congress. The Politburo and the Central Committee will take a decision at an appropriate time regarding electoral tactics in each of these states."

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

On 16 January, the West Bengal unit of the CPM held a public meeting in Singur, a tactical choice of location since it was here that Mamata Banerjee had whipped up a mass agitation against the then-in- power CPM over land acquisition for a Tata Motors plant. It culminated in the Left Front being uprooted from the state after a long reign of 34 years. What struck political observers at the 16 January meeting was an appeal by former Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee for a Congress alliance. "What is Congress leadership thinking today? We are not alone. Come and join us. Every opposition party should come and join us to unseat this undemocratic government," he said. Before that, on 27 December, at a massive rally in Kolkata where Yechury was present, Politburo member and Bengal Unit Secretary Surya Kant Mishra had invited "all parties" to join hands against the BJP and Trinamool.

The Left has wanted to construct such a coalition ever since the 2014 Lok Sabha election, and last June, it tried to forge a consensus on a leader who would head it. The state party unit proposed the name of Somnath Chatterjee, who had been expelled in 2008 when he decided to continue as Lok Sabha Speaker even after the Left's withdrawal of support to the UPA Government at the Centre then. The state unit recommended his re-induction. Sources in the party say that the proposal didn't go through because Chatterjee, at the age of 86, was not keen on active politics. A second name that cropped up was that of former Supreme Court judge Ashok Kumar Ganguly, but he too declined.

Mohammed Salim, a Politburo member and MP, sees no harm in aligning with the Congress. "Politics doesn't operate in a vacuum. It has to take into account changing scenarios and adapt for the larger good," he says, alleging that, "171 of our comrades have been killed under this criminal state government." Also, "West Bengal deserves to be [rescued from] this lawlessness," he says, adding that this should be done without any compromise on ideological issues.

Salim is a Yechury supporter. However, there are others in the party, like Biman Bose, who are vehemently against any tie- up with the Congress. They fear that it will weaken their ability to regain power in the state. "By starting to talk about an alliance with Congress, we have already demoralised our cadre, and they are not in good shape," says a senior state leader. "I don't understand what we are going to gain with Congress in an election we are certain to lose."

The CPM's chances of victory, argue those opposed to Yechury's alliance idea, are far higher in Kerala—chances that could be wrecked by news of a pact with the Congress elsewhere. In this state, the CPM-led Left Democratic Front hopes to gain from the turmoil that the ruling Congress-led United Democratic Front is currently in, given Chief Minister Oommen Chandy's troubles. "[A pact] would give the BJP a chance to say that we are a B team of the Congress. All such efforts would only help BJP," says a Politburo member. But some say they could portray it as the other way round: as the Congress being the Left's B team in Bengal, since the CPM would be the senior partner there. MA Baby, a Politburo member from Kerala, says nothing has been decided yet. "This is all speculation. A decision will be taken only after the Central Committee meeting."

Yechury and his team, however, seem set on a Congress alliance, and cite history to argue that it won't damage the party's prospects in Kerala. In the 2006 state polls, the Left swept to a two-thirds majority despite its support of the UPA Government at the Centre. "It cannot be said that an alliance in West Bengal may necessarily hamper the Left Front's strong prospects in Kerala," says another Politburo member.

External support and a pre-poll alliance, however, are two different things. Besides, a Congress-CPM alliance in Bengal reflects the desperation of two forces clinging to each other to stay afloat. How Yechury manoeuvres such a tie-up will be crucial to the Left's future. He has already made his first major blunder as general secretary by not joining the Grand Alliance in Bihar that won the recent polls there. "We were a minor player in Bihar and conditions were different there," says Salim. "We couldn't have gone with the Congress." Though the Left's Bihar tally rose from one to three seats, all were won by the CPI (ML). The CPM and CPI drew a blank.

Yechury might have lessons to learn from the late Left leader Shripad Amrit Dange. Back in 1964, India had only one Communist party and Dange and some other senior leaders had wanted to join hands with the Congress. Those opposed to it (and had differences over China) had walked out and formed the CPM. The CPI paid a price for its pro-Congress stand: it declined over the decades until its existence hinged on the CPM's fortunes. Yechury, thus, faces his first big test; for a failed experiment in Bengal would raise doubts over his leadership.

Meanwhile, the Congress has not said anything about such an alliance, though its state president Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury has proposed it to the high command in Delhi. Since the party is a minor player in Bengal, its focus is the Lok Sabha. Party President Sonia Gandhi has sent a senior leader to meet Banerjee twice to discuss an alliance which would help it dislodge the NDA at the Centre in 2019. "If Congress decides against an alliance with Left then it will be an egg on their face," says CPM watcher Achin Vanaik, former professor of International Relations and Global Politics at Delhi University. He is also sceptical of such an alliance reviving the party. "Rather than political and electoral manoeuvres, mobilising the people would have helped the Left movement," he feels.