India This Week

Furore over Shiv aarti; Hindi Akademi controversy; Costly sea link; Naxal jingles; BJP's mess and the Heritages Bill

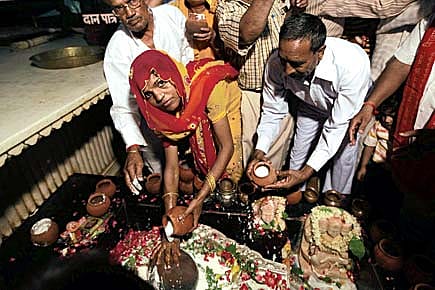

When Dalits Perform Shiv Aarti

Among other things, Dr Sambit Patra, an Oriya Brahmin surgeon at Delhi's Hindu Rao hospital, runs Swaraj, a project that seeks to bring Dalits into the Hindu fold. Swaraj began by holding ceremonies in which Valmiki (a caste derogatorily called 'bhangis') men wore the sacred Brahmin thread.

Last Saturday, a group of 50 Valmikis performed aarti at the historic Gauri Shankar temple in Chandni Chowk. A man who explained to a trustee of the temple got a public scolding: "I can't stop anyone from coming into the temple," said the trustee.

Unfamiliar with the ritual, many Valmikis looked a little lost. But the singing was helped by a T-Series cassette. Vimal Daank, a housewife from the Delhi 'village' of Chandrawal, demanded that a Valmiki idol be installed in the temple. "In the beginning, there was Valmikiji. He wrote the Ramayana and Hindus got their gods. Yet Hindus don't allow Valmiki idols in their temples," she said.

When the aarti was over, we asked head priest Shivanand Mishra what he thought. "The Shastras say the mere sighting of the temple door is enough for these people," he says. And is it good or bad that they've entered the gate and performed a group aarti? "What do I say about good or bad?" he replied. BR Ambedkar, who wanted Dalits to convert to Buddhism because of the ingrained inequalities of Hinduism, would have agreed with Mishra.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Shivam Vij

What Mirth Is Worth

Ever since Ashok Chakradhar's appointment a month ago as Hindi Akademi head in Delhi, the dust has refused to settle. Secretary Jyotish Joshi and consultative committee chief Nityanand Tiwari have resigned from the Akademi. Writer Archana Verma has written to the Chief Minister, and several others have issued statements. Their main objection? He is a hasya kavi, a poet of comic stage verse. We can't work under a vidushak (joker), they've said.

The controversy has occupied prime space in Hindi papers which mostly side with the anti-Chakradhar lobby. Jansatta wrote an editorial titled Hasya Akademi which stated the real problem: that he's close to the Congress.

Another source of controversy has been the Akademi's annual awards being put off. Chakradhar says the decision was his predecessor's. The award, we have learnt, was going to be given to Krishna Baldev Vaid but then some writers wrote to Sheila Dikshit quoting 'obscene' passages from Baldev's works.

Comic poet he may well be, but Chakradhar doesn't find any of this funny and points to the many notable contributions that he's made to Hindi literature. Such stalwarts as Namwar Singh have come to his defence, but it will be some time before everyone who wants to see his name in Jansatta and feel important will take it on the chin and move on.

Shivam Vij

Sealink Seachange

The recently-inaugurated Bandra Worli Sea Link, a modern Mumbai icon, was built for the sheen it would give the city. Escalating costs were ignored, and it eventually cost Rs 1,300 crore more than originally planned—all in the name of a priceless artefact. Problem is, Mumbaikars began treating the bridge as a priceless artefact: best admired from a distance. Officials of Maharashtra State Road Development Corporation Limited, which initiated the project, had estimated daily traffic at approximately 80,000 vehicles, earning them revenue of around Rs 29 lakh a day. Since the bridge was opened to the public, only 33,000 vehicles have used it per day, placing toll collections at Rs16.5 lakh. This might have something to do with falling traffic on the 'old' roads, where a reduction of nearly 40 per cent has been seen in vehicular traffic. However, officials are rethinking toll rates, and there are murmurs of a 20 per cent discount.

Battle of Minds, Not Guns

By the time some 25,000 security forces swoop upon Naxal strongholds in October this year, the Ministry of Home Affairs would have released a few radio jingles as part of a larger campaign against Naxalites—jingles that will tell people about the 'bad effects' of Naxalism. And then, the Central Reserve Police force (CRPF) and other paramilitary forces will sweat it out in the jungles of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa and other Naxal-affected states, trying to, in the words of a senior Home Ministry official, "weed out" Naxals from their hideouts.

The preparation for such an offensive has been on for some time now. The Ministry is now even ready to make satellite maps of Chhattisgarh's Abujhmarh area, the Naxal nerve centre, available to security forces. Officials say that once the forces go in, they will stay there for at least two years.

The plan sounds good, but only on paper. On ground, things turn out differently, as security personnel in West Bengal's Lalgarh will testify. It's been about seven weeks since they entered Lalgarh, which had earlier been taken over by Naxalites. Even after pushing in battalion after battalion of paramilitary forces, aided by special forces like the Cobra and the state police, not a single Maoist has been arrested so far. Maoists are roaming freely, while some of their senior leaders are still camping in the area. Last week, the state government admitted the Lalgarh operation had been a failure.

Lalgarh offers concrete lessons on how not to tackle insurgency. But the Centre seems to have learnt none. In October, when the ill-equipped CRPF and other forces try entering Naxal strongholds, they will face stiff resistance from highly-motivated Naxal cadres. Some CRPF battalions will be pulled out of J&K, where they would have already worked under extreme stress. In Lalgarh, soldiers battled it out in the absence of even basic facilities like safe drinking water. At least one soldier died of dehydration and many others fell seriously ill. In Naxal-affected areas, their biggest enemy will be the mosquito. Cases of cerebral malaria are rampant here. Besides, it will be difficult to distinguish a Naxalite from an ordinary tribal. In the absence of any clear-cut mechanism and the almost-certain lack of coordination between various forces, a soldier will wreak his frustration on the people, who are already living under extreme hardships. The operation will further isolate people.

Naxalism cannot be contained by, if you will, flying helicopter gunships. It can only be contained by winning the hearts and minds of people.

Rahul Pandita

The BJP Plays Hide and Seek

The BJP wants to introspect. And that will be done at a three-day Chintan Baithak later this month. Fearing that leaks to the press could have a negative impact on the party's performance in the coming Maharashtra election, it changed the venue of the meet from Mumbai to Shimla in the belief that with access to journalists curtailed, it will not face the same embarrassment it did during the national executive meeting in New Delhi in June. So far, it is not planning to hold press briefings either. Between them, the two dozen participants—top party leaders and members of the core group—ordinarily carry about twice the number of cellphones. For the party to assume that these will not be used to speak to the press is wishful thinking of the sort the BJP has become prone to.

Jatin Gandhi

Another Commission

The National Commission for Heritage Sites Bill, introduced in the Rajya Sabha in February, wasn't even referred to a standing committee in the Budget session. In all likelihood, the Bill will be quietly passed by Parliament one fine day without debate. It will be sad if that happens, because it needs to be thrown out.

The Bill seeks to establish yet another commission for heritage sites, serving mainly to conserve sites covered neither by the Archaeological Survey of India nor the archaeology departments of the states. It will also recommend sites that should be on the Unesco World Heritage list.

If the ASI is currently found lacking in its job, it's because of lack of powers and funds. The solution cannot be to create yet another toothless body. The Bill seems to be creating the mother of all heritage bodies: 'Among the important functions of the Commission are formulations of short- and long-term policies in respect of conservation, protection and management of heritage sites, laying down standards for development, formulation of guidelines, establishment of a heritage sites roster.' But what of the conflicts of interest that may arise between this body and the ASI?

India ratified the 1972 Unesco World Heritage Convention in 1977, and 32 years later, the Government realises the lack of a legislative framework to meet its obligations. It will perhaps take a few more decades to realise it takes much more than a commission.

Shivam Vij