If Only Khurshid Would Focus on Work

The UPA's law ministers get a big 'F' in fixing the country's broken judicial system

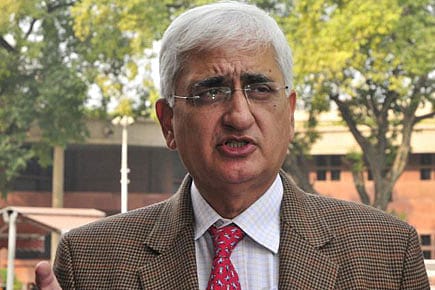

Since 2004, when the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) first came to power, the Ministry of Law and Justice has seen three different law ministers: HR Bhardwaj (2004–09), Veerappa Moily (2009–11) and Salman Khurshid (2011–12). The only common denominator among the three is their lackadaisical attitude to reforming India's broken judicial system.

Since 2004, according to the Rajya Sabha website, the Ministry has piloted a total of 24 legislative bills in Parliament. Of these, only nine were directed at the judiciary while the remaining pertained to personal, electoral and general administrative laws. Of the nine, only four—the National Tax Tribunal (Amendment) Bill, 2007; The High Court and Supreme Court Judges (Salaries and Conditions of Service) Amendment Bill, 2008; The Supreme Court (Number of Judges) Amendment Bill, 2008 and The Gram Nayayalayas Bill, 2008—have become laws. The first three are hardly judicial reform. One seeks to save the National Tax Tribunal from a severe constitutional challenge in the SC, another raised the salary of HC and SC judges, while the third bill increased the number of SC judges marginally.

Only the Gram Nayayalayas Bill, 2008, was a major step towards reforming the judicial system at the village level. However, even this bill got through Parliament only in the second attempt. The first version of this bill, introduced as the Gram Nayayalayas Bill, 2007, was withdrawn. The concept of Gram Nayayalayas was proposed by the Law Commission in 1986—more than 20 years before it finally became law.

Of the remaining bills, the Judges (Inquiry) Bill, 2006, lapsed after the dissolution of the Lok Sabha in 2009. It was then re-introduced

in 2010, with amendments, as the Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill, 2010, and is yet to be debated in Parliament. The remaining two bills are the 114th Constitution [Amendment] Bill, 2010, and the Commercial Division of High Courts Bill, 2009. The first, originally conceived by eminent lawyer Fali Nariman when he was a nominated member of the Rajya Sabha, is a relatively simple piece of legislation to increase the retirement age of all High Court judges to 65 years from the current 62 to temporarily reduce vacancies in the HCs. One would have thought that this legislation would have breezed through Parliament in no time, but it has been pending for over two years now. The Commercial Division of High Courts Bill, 2009, aimed to create a special procedure at the level of high courts to fast-track high-value commercial litigation valued at more than Rs 5 crore. This bill was based, in large part, on the 188th Report of the Law Commission and was passed by the Lok Sabha without any debate. The Rajya Sabha referred the bill to a Select Committee which submitted a detailed report on the bill along with a series of dissent notes from several members who were seriously opposed to the bill. The dissent should have alerted the Government to the mood of the House, especially when it did not have a majority in the Rajya Sabha. However, when the bill came up for discussion in December 2011, the Union Law Minister Salman Khurshid appeared to have been taken by surprise. When the opposition led by Arun Jaitley launched a well-articulated critique of the proposed reforms, the Law Minister's only response was to withdraw the bill with a promise to amend it. Hadn't Khurshid read the Select Committee's report before the debate?

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The UPA's law ministers get a big 'F' in fixing the country's broken judicial system. It isn't as if there is nothing to fix. There has been a virtual political consensus that appointments to the higher judiciary be made more transparent. Currently, appointments are made by a highly opaque collegium of the senior-most judges of the Supreme Court. But we are yet to see a single legislative proposal from the Law Ministry on this issue. Similarly, there is a virtual consensus among members of the Bar on the need for more circuit benches for high courts and the need to fill existing vacancies. Another topic of enormous litigation has been the constitutionality of various tribunals created under various laws. The Supreme Court, in a judgment in May 2010, while deciding the constitutionality of the National Company Law Tribunal, expressly directed the Law Ministry to control the administration of all tribunals established by Parliament. The Ministry has not budged an inch to carry out the SC's directions.

The Law Commission of India, which operates under the Ministry, has suggested countless ways of reducing arrears and initiating judicial reforms. Unfortunately, the Ministry rarely if ever pays heed to the often-sage advice of the Law Commission. Forget big-ticket controversial judicial reforms, the Ministry has shown little appetite for even minor reforms. One such example is the Judicial Statistics Bill, 2004, introduced in Parliament by Nariman. It could have had a ripple effect similar to that of the RTI Act, 2005. It sought to create a mechanism not only to collate judicial statistics across the country, but also to use this data to assess the performance of individual judges. The entire cost of implementing the bill was estimated to be no more than Rs 10 crore. But, Nariman's idea was torpedoed by Bhardwaj. There is little hope of things changing under the present minister.

The author is an advocate and co-founder of the Pre-Legislative Briefing Service (PLBS), a think-tank