Half Life

After two decades of bloody conflict in Kashmir, thousands of women are not sure whether they should call themselves married or widowed

After two decades of bloody conflict in Kashmir, thousands of women are not sure whether they should call themselves married or widowed

The stone-pelting had just begun at Maisuma in downtown Srinagar when Tahira alighted from the bus, tightly clutching her youngest son's hand. A group of young Kashmiris had assembled on the fringes of the historical Lal Chowk, setting off yet another intifada (uprising) against the Indian State.

Some of them threw Coca-Cola bottles at the policemen, in return for teargas shells. "Why are they wasting cola?" asked Tahira's son, Saahil. And then he tugged at his mother's sleeve: "Let us go back home, ma." On their way back, Tahira remembers, she had shed tears. She didn't know whether she was feeling sad or relieved.

It was the stone-pelting that had saved her from a major embarrassment that day. Earlier in the day, Saahil had returned from school and demanded to be taken to Nehru Park, alongside Srinagar's Dal Lake. "That is where Arshad's parents take him every week," he had made it known. Tahira had checked her sugar jar more than twice to count the few currency notes she kept there. She only had Rs 150. A shikara ride, she knew, would cost her at least that much. And if she gave that money to the shikarawala, how would she commute back to her seven-by-six-foot dwelling in Old Srinagar? It was the stone-pelting that had come to her rescue.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

It is no big deal to take a child for a shikara ride in the Valley. But if your husband has been missing for seven years, raising three children on a seamstress's meagre income can be daunting. More so, if the middle son is sinking deeper into depression as the youngest demands an outing. In school, 11-year-old Riez is asked about his father. He doesn't reply. He just leaves quietly and cries in the darkness of the room for which his mother pays a monthly rent of Rs 600. "He had almost lost his vision because of excessive crying," says Tahira, "and is now under a psychiatrist's supervision." And the eldest son? He talks very little. He faints every now and then, besieged by the memory of his father.

Tahira's husband, 35-year-old Tariq Ahmad, had packed his bags in late 2002. He wanted to start a new life in Delhi. The couple had once worked in the national capital, and Tariq wanted to give it another try for the sake of his children. "I packed food for him and he left," recalls Tahira.

Days passed by, but she had no word from her husband. At first, she thought he might be busy. After a week, she began to panic. Phone calls yielded nothing. Going to the police offered little respite; it had only been about a year since Parliament had been attacked in New Delhi. Finally, one day, Tahira was told that Tariq was in Udamphur jail, near Jammu. "We rushed there, but it turned out to be someone else," she says.

It has been seven years now, and there is still no trace of Tariq. He simply disappeared, and that's that.

The thing that won't go away is this: in the Valley, his story is hardly exceptional. In the two decades of armed conflict in India's northern-most state, thousands of people, mostly young men, have gone missing. Human rights activists say the number could be as high as 10,000.

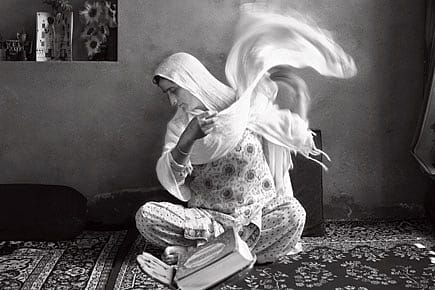

For women like Tahira, it means a life to be lived in limbo. They go through their daily paces. They wait. They weep. They brood. Occasionally, they stir. They even jump, against the limitations of likelihood, at the slightest hint of news about their missing husbands. It is always in vain. In Kashmir's conflict-ridden lexicon, women such as Tahira are known as half widows.

Security agencies in Kashmir have a standard explanation for these disappearances—the men have gone across the border to Pakistan for arms training. But what, ask locals, about those who were seen being picked up by armed personnel in uniform and never heard of since?

That is left unanswered. As a rule. Invariably.

Does Tahira ever think of remarriage?

"No, never. Till I die, I will wait for him," she says. "In the 10 years we spent together, we never even ate in separate plates."

Their children are not giving up either. "When my father comes back, we will have our own fridge to keep this," chirps Riez, pointing to a couple of cola bottles bought from a nearby shop.

WHERE THE PAPERS HAVE NO NEWS

"The government has never responded to our figures," says Khurram Parvez of the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP). "We keep hearing that 'normalcy' has returned in the state. If it has indeed, why are they not allowing civil rights groups to look into these disappearances?"

According to Parvez, the recent spell of democratic rule in Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) has not brought much relief. During the three years that the Srinagar-based People's Democratic Party (PDP) ran the state government (in coalition with the Delhi-based Congress), as many as 122 people were victims of "enforced disappearance", as Parvez puts it. The Congress-led government under Ghulam Nabi Azad—which took over from the PDP midway through the elected assembly's term—had claimed that disappearances had dwindled under its rule. But according to the APDP records, no less than 111 people in the state had gone missing during this period.

Some eight cases have been reported ever since Omar Abdullah took over as J&K's Chief Minister about six months ago.

In Baramulla's Zogiyar village, most adults know that the mountain range that forms the backdrop to their houses is used as a route by many to sneak over to Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). Nazir Ahmed Mir also knew this, but he was content living with his family and working as an electricity lineman.

On a dark May night in 1990, Nazir lay in bed with his family. Militancy was at its peak and no one dared venture out after sunset. Some shouts and a series of knocks woke the family up. Nazir's wife, Atiqa was just 18. She cannot forget Nazir's post-midnight thumping—on the door and in her chest. Telling her not to worry, Nazir got up to open the door. Surrounded by heavily-armed soldiers of the Indian Army's 16 Dogra regiment, a local man, his face concealed in a monkey cap, pointed a finger at Nazir. That was it. He was handcuffed and dragged off to an Army vehicle. "He kept pleading that he was just a small-time employee," recounts Atiqa.

Atiqa has spent 19 years looking for her husband. At first, the police had even refused to lodge a complaint. Atiqa's father searched for his son-in-law in various jails. "Thrice we were sent visitor slips to see him in three different jails," she says, "but he was not there." Unable to bear the pain, her father passed away. Atiqa had to raise her four children all by herself.

The wait wasn't entirely eventless. Eleven years after his disappearance, Nazir's family was handed a document—his death certificate. At least his job could now be given to his eldest son.

As for justice, Atiqa says: "I have attended hundreds of hearings, but nothing has come out of it." The case is still pending in J&K High Court. Meanwhile, the family has got Rs 1 lakh as compensation. The money, though, has settled nothing. "We will return that money with interest if my father comes back," says her daughter Tasleema, wiping tears from her mother's eyes.

Atiqa's daughters have now grown up. "How do I get them married?" she asks, painfully aware of her dependence on others. But speaking is cathartic in its own way. And maybe more. "Will the government read your report?" she asks us. Then she looks out of her window—as an Army convoy passes by. "At least they could have shown me his dead body. I would have reconciled to that fact once and for all." The wait doesn't end.

It's déjà vu in another way, too: a boy appears with a few bottles of cola. "This Coca-Cola is very much part of our lives now, just like the Army," remarks their neighbour, guiding us towards the bottles, their rusty caps yanked off. He is an old man, with prayer marks on his forehead, curious about our presence in Zogiyar.

STILL HAVEN'T FOUND

In the neighbouring village of Sheeri, Nahida was 40 days old when her father, Farid Bhat, crossed over in late 1990. His brother, a militant, had been killed by a rival group. Bhat wanted revenge.

"He didn't even tell me that he was leaving," says his 33-year-old wife Hanifa. She was clueless about his whereabouts for years on end. Until he called one day. "I kept on crying over the phone. He said he was in Muzaffarabad and wanted me to join him," says Hanifa. But the promised reunion never happened.

It was not for lack of effort. On February 16, 2005, one day after YouTube officially came into our lives, the government flagged off a bus service between Srinagar and Muzaffarabad. Hanifa has been trying her utmost to get a passport ever since. "I spent lot of money to get one," she says. "So many people fleeced me, falsely promising me to a passport."

Farid's mother got one, though, and so did his daughter. Three years ago, the daughter visited her father, and chose to stay on when her father asked her to. "She calls sometimes, and both of us just cry over the phone," says Hanifa. Two years ago, Farid sent Hanifa a talaknama, dissolving the marriage. "My regret is that I waited for him so long—and he didn't," says Hanifa softly, running her fingers over comforting verses of the Quran.

Hanifa is not the only one in her family to be a victim of the strife in the Valley. Her own brother, Abdul Rashid, a taxi driver, was caught by the Army in 1990. He was never seen again. After waiting for a few years, his wife, who shares her name with her sister-in-law, remarried. Her two daughters from her first marriage live with her first husband's family. In Pringal village, near Uri, she stays with her second husband. Shafiqa, her eldest daughter, visits her sometimes. When she misses her, she weeps.

What if her first husband returns one day? What will she do? "I am devoted to my husband now. A marriage is a pact, nobody can undo it," she says, stealing a glance at her husband, Mohammed Dilawar, who's watching. "You haven't had anything. We don't leave guests like this," he says. "At least have a Coca-Cola."