Grant Maratha

Does Maharashtra's dominant social group deserve the quota promised by the state government?

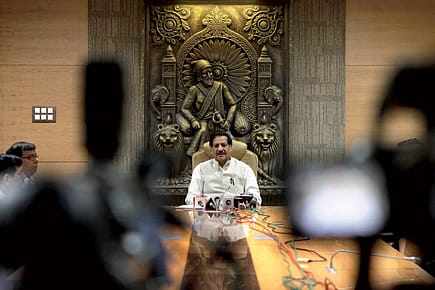

On 25 June, a beaming Maharashtra Chief Minister Prithviraj Chavan announced that his government would reserve 16 per cent of state jobs and educational seats for Marathas. The CM and his deputy Ajit Pawar—both of whom are Marathas themselves— looked pleased with themselves. With Assembly polls slated for October this year, perhaps they believed they had scored over their BJP and Shiv Sena rivals, most of whom are also Marathas.

As Chavan and Pawar seem to see it, the move is a lifeline for the state's Democratic Front government, a coalition of the Congress and Nationalist Congress Party (NCP), which has seen its re-election chances drop drastically over the past two years or so. Together, the two ruling parties won only six of the state's 48 Lok Sabha seats this summer. Marathas, who are estimated to constitute 30 per cent of Maharashtra's population and hold sway in at least 200 of its 288 Assembly segments, are being looked upon to revive the coalition's prospects. What strikes observers hard, however, is the utter cynicism of the announcement. The government has sought to dovetail the Maratha quota with a 5-per cent reservation for Muslims, suggesting that both groups need help to overcome deprivation.

Applied to Marathas, that suggestion has stunned those who are familiar with the state's social power structure. Not only are they politically, culturally and socially dominant as a group, many of them are financially well placed.

Consider the numbers.

An estimated 3,000 Maratha families control 72 per cent of the state's landed property. Some 171 Maratha families may be said to be politically dominant. By one count, there are 22 prominent Maratha 'dynasties' in the state.

A database on elected representatives from 1960 to 2004 shows that of the 2,430 MLAs the state has had in that period, as many as 1,336 have been Marathas. Of the 17 CMs the state has had, 10 have been of this community, Chavan included. Nearly half the current Assembly's seats—135 of 288—are held by Marathas. The group also plays a significant role in the state's economy, with Maratha- owned businesses accounting for a major chunk of it. So how do they qualify for affirmative action?

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

The government has gone out of its way to classify Marathas as a new 'Educationally and Socially Backward Class' to justify its move. However, they have never been a marginalised group or faced any social stigma. Also, as many say, they have always considered themselves to be 'forward', akin to Kshatriyas, and they find being placed on a bench with 'Backwards' hard to digest.

"We have always prided ourselves as being a 'forward caste'. We do not want the 'Backward Class' tag. In India, it's taboo," says Sridhar Salunke, 35, a medical representative. "I am not happy to be clubbed with Backward Classes. Shivaji Maharaj was an ancestor of Marathas. Was he of a Backward Class? Then why should we be?" asks an angry Salunke, who has promised himself never to avail of a quota. "Give the poor these benefits, but don't put us all in the Backward Class basket," says Pradnya Shelar, a student, "One day, I am from a 'forward' class, and the next day I become a Backward Class person. How is it going to help me?"

Historically, some say, the Maratha community was formed by the amalgamation of several royal clans that settled in the region from different parts of India. Today, many Marathas trace their lineage to warriors of the clan of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the king of Maharashtra who freed the state of Mughal rule in the 17th century. They identify strongly with him even now, and count such leaders as former President Pratibha Patil, NCP chief Sharad Pawar and former CMs Shankarrao Chavan, Vasantdada Patil and Vilasrao Deshmukh as their own. Other famous Marathas include the 13th direct descendant of Shivaji, Chhatrapati Udayanraje Maharaj, spiritual godman Bhayyu Maharaj, public prosecutor Ujjwal Nikam, education barons DY Patil, Patangrao Kadam, Datta Meghe and Balasaheb Vikhe Patil, and pop culture celebrities Ritiesh Deshmukh, Madhu Sapre and Vijayendra Ghatge.

Maratha education barons control at least half of the state's educational institutions. Dr DY Patil, the current Governor of Tripura, for example, runs numerous institutions under his name, while Dr Patangrao Kadam is vice-chancellor of Bharatiya Vidyapeeth. Dr Balasaheb Vikhe Patil owns the Pravaranagar group of institutes. While most of these are built on land allotted by various state governments at nominal rates to offer affordable education to the masses, their fees have risen beyond the reach of most students.

Scoffing at the quota, says Prakash Ambedkar, great grandson of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: "It is solely a political move for benefits in the Assembly elections… Of the 200 sugar factories [in the state], 168 are controlled by Marathas. An estimated 70 per cent of the district co-operative banks are controlled by them. Do they need reservation?"

Union Minister for Minority Affairs Dr Najma Heptullah has also called it 'vote bank' politics. "Constitutionally, it is not allowed," she told the media, "It will be stopped by the courts."

Ketan Tirodkar, a former journalist and activist, has filed a PIL in the Bombay High Court arguing that Marathas are not a caste but a linguistic group. It is expected to come up for hearing shortly. The quota may also violate a Supreme Court order that placed a 50-per cent cap on all reservations. Legal experts believe that the Maratha quota will not hold up to legal scrutiny, as it would take the overall percentage of reserved posts and seats above the halfway mark.

A defiant Chavan, though, is determined to have his way. Sharad Pawar, meanwhile, has made the NCP's stance on the issue clear. "We are not a party of sadhus and sants," he said, "It is a long pending demand that we have fulfilled. We did not consider whether we will benefit from this. But if we do, so be it."

The buzz in political circles is that Pawar was the move's mastermind. While he himself has not spoken in favour of a quota for his 'own people', it is well known that community leaders such as Maratha Mahasangh President Vinayak Mete have been making this demand with his blessings. Another Pawar supporter, Chhatrapati Sambhajiraje, a descendant of Shivaji who heads the Maratha Arakshan Mahamorcha, had issued an ultimatum to the state government to expedite a quota for Marathas. He had warned that the Mahamorcha would oppose the government in the next polls if it failed to do so. "The government's ready acceptance hints at its being a Pawar move," says a source.

Rajeshwari Deshpande, professor of Politics and Public Administration at University of Pune, has done research on caste-based reservation and its impact. According to a paper presented by her: 'Along with the numerical preponderance, the Maratha dominance was a result of land ownership in Maharashtra and a historically nurtured sense of identity.' She says the Congress party appropriated this sense of identity under its Bahujan Samaj ideology, by which the caste and cultural conflict in Maharashtra was essentially seen as a conflict between Brahmins and the rest—with Marathas seen as leaders of the latter. 'The construction of the Bahujan ideology provided a much needed cultural tool to the Congress and Maratha dominance became synonymous with the politics of Maharashtra,' writes Professor Deshpande.

It was Mandal politics that upset that paradigm. In 1980, the Mandal Commission had classified Marathas as a 'forward class'. In the 1990s, with the BJP and Shiv Sena upholding Hindutva to rally broad support, the Maratha solidarity in favour of the Congress began to weaken. Ever since, the Congress and its breakaway NCP have feared that Marathas have drifted away from them.

Matters reached a breaking point in 1994, when Sharad Pawar as Chief Minister renamed Marathwada University after Dr BR Ambedkar. This angered Marathas, who vowed to defeat the Pawar government. In the 1995 Assembly polls, Pawar lost power and the Shiv Sena-BJP won. Over the past decade, the poor among Maratha farmers have been leaning towards the Sena.

In 2009, the Congress-NCP mooted the idea of granting Marathas OBC status. It did not happen; the state's Backward Commission argued that they faced no oppression. In 2003-04, the National Commission for Backward Classes did not approve of OBC status for them either. As of now, OBCs have a 27-per cent quota, and a subgroup of Marathas who are mostly farmers, known as Kunbis, are classified as such and can avail of it. Deshmukhs, Kadus and other Marathas cannot. Many suspect that reserving posts for all Marathas is a device to block the political aspirations of OBCs.

Senior journalist Abhay Deshpande feels that the state needs to relook at its reservation policy. "Maharashtra's agriculture is rain-fed," he says, "There is only 18 per cent irrigation in the state—much below the national average. Therefore, the farming community, which is predominantly Maratha, is overdependent on the monsoon. With several districts of Maharashtra facing severe drought in the last decade, farm production has fallen. This has impacted their income and status. However, this cannot be grounds for reservation. Marathas have never been a marginalised class."

The state BJP, meanwhile, is divided on the issue. According to the state unit president Devendra Phadanvis, a Brahmin, the government is clearly eyeing votes. "After fooling the people for 15 years, they have now brought in reservation," he says, "It is a hasty decision. The government has not checked if it can withstand the legal and constitutional test."

In contrast, the BJP Leader of the Opposition in the Legislative Council, Vinod Tawade, a Maratha, favours the plan. "The reservation [level] should be higher. However, if this quota is challenged in court, we will support the state government," says Tawade.

Also read: Reservation – It's a political gimmick