Amit Jogi: The Man Who Knows Too Much

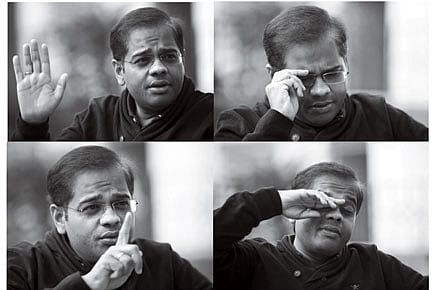

Amit Jogi sits quietly on the lawns of 117 North Avenue, enjoying the Delhi winter sun on a Tuesday afternoon. He is alone except for some staff who are setting up lunch. His mother Renu Jogi, also an MLA from Kota, Chhattisgarh, occasionally checks on him. Soft-spoken, bespectacled and clad in a shirt and trousers, 38-year-old Amit Aishwarya Jogi appears untouched by all the controversy around him as he talks about his youth and his interest in European history. "Delhi is like my hometown because I have spent all my childhood here," he says. "I have spent my golden years in this city." Ever since he moved to Raipur in Chhattisgarh in 2000 after his father Ajit Jogi became its Chief Minister, trouble has constantly courted him. "This is part of public life," he says, with confidence. "When Naxals killed senior Congress leaders in Darbha valley in 2013, some BJP leaders like JP Nadda and Narendra Singh Tomar blamed it on me without any evidence. I have gone through several such incidents. It doesn't affect me," he adds.

This time round, however, Amit Jogi has not managed to escape unscathed. A recent controversy over an audio tape allegedly pointing to his involvement in fixing an election has resulted in a six- year-long suspension from the Congress. Amit Jogi is in Delhi to present his case before the party leaders. The Congress may even oust his father, Ajit Jogi, who had been suspended in 2003 over his role in buying BJP MLAs to form a government, but was reinstated within a month.

The audio tape that surfaced in the last week of 2015 contains a purported conversation about the Antagarh Assembly seat by-election last year among six people— Amit, his father, Manturam Pawar, the Congress candidate who withdrew his nomination at the last minute, Puneet Gupta, son-in-law of Chief Minister Raman Singh, and two others. Pawar's withdrawal at the last moment meant that the Congress had no time to field another candidate, resulting in an easy win for the BJP. Infighting within the Congress state unit is nothing new; it was one of the reasons the party couldn't gain enough seats in the 2013 Assembly polls despite a favourable wave. This fight has now culminated in Amit Jogi's expulsion. "The newspaper which released the audio tape said it was a 'purported conversation'. Of the six people reportedly in it, five have denied that it is their voice," Amit says. "How can you suspend me without even proving the authenticity of these tapes?"

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

A week later, the story got another twist when Firoz Siddique, the man who released the earlier audio tape, came out with another in which he appears to be in conversation with Chhattisgarh Congress President Bhupesh Baghel. Baghel is heard directing Siddiqui to approach the newspaper with the audio tapes and to expose the Jogis. The mudslinging between the two factions has upset the party high command in Delhi, which is in no mood to reinstate Jogi.

The Jogis have been at the centre of politics in Chhattisgarh ever since the state was created in 2000. Ajit Jogi was its first Chief Minister. He started schemes for Dalits and Tribals and grew immensely popular with these communities, while also tactfully dealing with his rivals within and outside the party. His three- year tenure saw the rise of Amit in state politics. The son acted as chief minister behind the scenes, dealing with the bureaucracy and sanctioning government contracts.

Going by Amit Jogi's election affidavit, there are 12 legal cases registered against him. It all began in 2003, when he was accused of conspiring to murder Ram Avtar Jaggi, a senior leader and treasurer of the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) in Chhattisgarh. Satish Jaggi, Ram Avtar Jaggi's son, remembers the dreadful night of 4 June when his father was killed. He was returning home when he saw his father's Alto at Jaison Chowk in Raipur. His first thought was that the car must have met with an accident, but a far worse fate had befallen his father. He had been shot dead. "I knew the Jogis were behind the murder," says Satish Jaggi. It took two years for Amit, the prime accused in the case, to be arrested. He was granted bail after spending 10 months in jail. The shooter, Chiman Singh, was arrested in 2005 from Assam. Amit was once again arrested in May 2007, only to be acquitted of the murder charges due to lack of evidence. Of the 29 accused in the case, 28 were convicted and one set free. That man was Amit Jogi. "In the last few years, they have gone to the higher courts several times, but they have not been able to prove any charges against me," says Amit. "This is part of a larger conspiracy to diminish Tribal leadership in the country."

There is a joke doing the rounds in Chhattisgarh—that if Ajit Jogi were to form his own party, its symbol would be a CD. "Amit is the CD king. He must have more than 200 tapes of politicians and people with whom he wants to settle scores," says a senior state Congress leader. "Over time he has used these tapes to his advantage. Now he is facing the brunt of it." Devendra Yadav, the Mayor of Bhilai, blames Amit for concocting a CD controversy against him when he was president of the state unit of the NSUI. Firoz Siddique, the man who is behind the recent audio tapes, is said to have been Amit's co-conspirator. In fact, he was convicted in the Jaggi murder case and is out on bail. A caretaker, Siddique quickly climbed up the ladder once he became close to the Jogis. He is said to have carried out sting operations for the family with such regularity that people in politics reportedly stopped discussing important matters over the phone. But after he was convicted in the Jaggi murder case, an angry Siddique decided to turn on Amit Jogi.

Amit Jogi denies his association with Siddique. "This is baseless. He is a convicted criminal in a case in which I have been acquitted. That is why he is acting against me," he says. Amit Jogi even filed a complaint with the police on 23 December 2015, alleging that Siddique had been sending him messages demanding money and threatening to defame him.

Then there is the mystery of his birth. Amit Jogi was born in Dallas, Texas, on 7 August 1977. In 2001, he applied for Indian citizenship. On 15 January 2002, the Central Government accepted his application. Some local leaders, however, allege that he still holds a US passport. Amit laughs it off. "No one can choose his birthplace," he says. The Supreme Court on 4 January this year ordered an enquiry into his US citizenship in a case filed by Sameera Paikra, the BJP Assembly candidate from Marwahi defeated by Amit Jogi by a margin of over 40,000 votes in the 2013 state polls.

This is where the story starts to get murky. In 2013, just before filing the nomination for contesting the Marwahi Assembly seat, Amit applied for a caste certificate. He submitted a report from the Patwari of Gram Sarbahara, in which he mentioned his place of birth as Gram Sarbahara, Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh. The Patwari report also notes his date of birth as 7 August 1978, which is different from what was mentioned in the application for Indian citizenship.

The Jogi family's claim of being members of a tribe is another matter of controversy in Chhattisgarh. Ajit Jogi's caste certificate, obtained in 1967 from Pendra Road, would make them Kanwar Tribals. However, the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes rejected it and a case was filed against him. Ajit moved the Supreme Court, which, on 13 October 2011, ordered a probe of his caste. The enquiry is still pending. The family's land records also point to their non-Tribal status. In undivided Madhya Pradesh, under Section 165 of the MP Land Revenue Code, a Tribal needed the Collector's permission to sell his property to a non-Tribal. But in 1967, when Ajit Jogi's father KP Jogi sold a piece of land to Govind Prasad Rai—the registration copy is with Open— he mentioned his caste as 'Christian' and did not obtain the aforesaid permission. This means that KP Jogi had claimed to be a non-Tribal. Also, when he bought some property in 1966 from a Tribal, Sumer Singh, the latter took permission from the Additional Collector, Bilaspur, to sell his land to a non-Tribal.

Senior Congress leaders allege that Ajit Jogi has tried to neutralise every possible threat to his leadership. In the 2013 Assembly polls, he openly threatened to put up his own candidates if the party did not bow to his demand for seats. The Antagarh tape is just one more incident that has shifted the focus back on the family. "If we are all that bad then why would people choose us as their representatives?" argues Amit. "None of the allegations has been proven. I am open to a narco test if that is what the Government or the party wants. Rumours are only rumours." But the pace of investigation in the cases against the Jogis puts a question mark on the judicial system.

What is needed is a time-bound probe of the charges. But until then, the Jogis can have the last laugh.