Murugan’s Moment

A HEAD OF THE annual Kanda Shashti festival in Tamil Nadu in November, a petitioner asking for the ceremony of Soorasamharam—a mythic tradition recreated at the Murugan temple in Tiruchendur, Thoothukudi district, where he is believed to have vanquished the demon Soorapadman—to be held on the seashore in the presence of media crews, made an error of judgement. The Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court acceded to the petition on November 19th, clarifying that the Tiruchendur Murugan temple authorities intended to conduct the ceremony on the shore as per tradition, albeit without the usual throng of devotees, but it did take umbrage at the submission that 'the ancient scripture Skandapurana was brought from Nepal and it was translated in [sic] Tamil by Katchiappa Sivachariar'. 'Lord Muruga is considered to be the Tamil God and his six abodes are located at Tamil Nadu and except in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Kerala, other parts of India are not having [sic] any temple for Lord Muruga. When that is the position, this Court is unable to understand as to how the scripture written in another language was brought from Nepal and later, it was translated in Tamil,' the court order read. A century and a quarter ago, Hara Prasad Shastri and Cecil Bendall discovered a palm-leaf manuscript of the Skanda Purana in a Kathmandu library and dated it to 800 CE, making it one of the oldest manuscripts found in Nepal. If Katchiappa Sivachariar's 12th century Tamil recension of the Skanda Purana never gained popular acceptance—except in Sri Lanka—it is because Tamil Nadu's relationship with Skanda, or Murugan, predates it. While Kartikeya did not make a big splash up north, Murugan remains an unbounded and immortal presence across Tamil Nadu, capable of inspiring a filial devotion in non-believers and Tamils of other faiths.

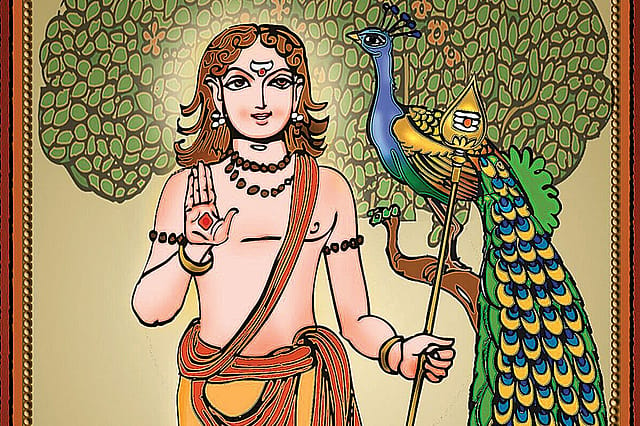

A primordial folk deity of the hills worshipped even before the Sangam age (BCE 600-300), Murugan's renown was such that Saiva texts written after 600 CE, such as the Thevaram, began to identify him as Siva's son, and Vaishnava texts accorded him pride of place as Vishnu's nephew. 'Post-13th century, Murugan gained prominence as the middle ground between Tamil Saivas and Vaishnavas, who had been at loggerheads. How far this campaign to unite the Hindu factions against the Muslim invaders was successful is debatable,' says A Subramanian, a veteran folklorist.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Despite attempts to plug Murugan into the mainstream Brahminical pantheon, his cult in Tamil Nadu draws its life from the soil, like a natural growth. Originating in the penumbra of prehistory, when people believed in the mysticism of the world around them, Murugan, or Murugu, is a spirit with both positive and negative valences that can possess humans, make them break into frenzied dance, cure illnesses and predict the future. He is Seyyon, or Sevvel, the Red One, hailed in Sangam age poetry as a god of beauty, youth and valour. His symbols—the cock that is his insignia, the peacock he sits atop, and the spear or the vel that is his weapon—are ancient totems that have been found at megalithic sites, including Adichanallur in southern Tamil Nadu. Over time, as the Tamil country came to be tenanted by lakhs of gods, only the most popular among them retained lordship of the landscapes. The hills, or the kurinchi tracts, belonged to Murugan, also known as Guhan, the cave-dweller—a skilled hunter who falls in love with and marries a tribal girl, Valli. Murugan's anthropomorphism was now complete; Tamils had thoroughly humanised him. It is not just the Kuravars who claim Murugan as their own—nearly every community, from the Nagarathar to the Sengunthar, has a story about their own divine ancestry featuring Murugan.

It is understandable, therefore, that BJP, which is trying to mop up unaligned Hindu votes and mobilise the non-dominant communities among the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and the Scheduled Castes (SCs), invoked Murugan when it wanted to employ the tried and tested trope of a yatra. The Vel Yatra to Murugan's six abodes in Tamil Nadu, from Tiruttani to Tiruchendur, was announced in response to Tamil rationalist YouTube channel Karuppar Koottam's allegedly obscene interpretation, in a video posted on July 13th, of the Kanda Shashti Kavacham, a popular early 19th century hymn to Lord Murugan. Denied permission by the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) government in Tamil Nadu, the yatra has failed to rally support on the ground since it took off on November 6th, but what it has done is grabbed headlines and helped BJP— which has a new president from the Arunthathiyar community, classified as an SC, incidentally named L Murugan— drag religion into the poll arena. The symbolism of evoking a god of war and victory in a Tamil Nadu that is headed for the polls is hard to miss. In a state where the Dravidian tenets of self-respect and social justice and caste, and party loyalties have determined electoral outcomes, BJP is trying to shift the goalposts. Consider, for instance, that when former Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) President M Karunanidhi undertook a padayatra to Tiruchendur from Madurai in 1982, the cause was justice for a Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department official, C Subramaniam Pillai, who was found dead under suspicious circumstances in November 1980. The march forced the then AIADMK government to form a commission of inquiry.

WHILE KARUNANIDHI famously questioned the veracity of the Ramayana, he did not speak ill of the Tamil god Murugan. A god who fosters multiple narratives, Murugan is always depicted as a victor but not as a triumphalist. He has the grace to spare Soorapadman's life by turning him into a peacock, and even declines Indra's offer to take over as lord of devaloka to remain senapati. If prevailing mores of worship mirror the shifts in discourses of power in society, the fact that his preferred offering was that of goat blood and flesh mixed with rice in the Sangam era and that it is plain rice and pickle along with savouries and sweets today tells us something. "Murugan would have loved a good biryani," says Subramanian. "There are two aspects to his worship in Sangam literature: spirit possession and animal sacrifice. It is only after the 3rd century AD that temples were established according to agamas and gods became civilised. While Murugan transitioned from a folk deity to a popular god, he is not an equaliser like Lord Ram of Ayodhya. The Brahmins, who only accept him as Kartikeya, do not participate in the folk traditions and rituals at Murugan temples. The Vaigasi Visakam festival to celebrate his birth attracts a swathe of devotees from OBC and SC communities but the Kanda Shashti is more elitist, finding acceptance among dominant OBC castes," Subramanian says.

"While you will find innumerable Subramaniams and Balasubramaniams, with a confusing plethora of variant spellings and endings, among Tamil Brahmins, not one is named Murugan. The major Murugan temples also attract predominantly non-Brahmins and in many of the festivals, self-mortification austerities such as alagu kuthuthal (piercing one's body with rods or spears, a ritual most commonly in evidence during the Thai Poosam festivities at the Palani Murugan temple) are practised exclusively by them," says Tamil writer and historian AR Venkatachalapathy. "Murugan is the original Tamil god—young, comely, virile. He is propitiated by the shaman. From the time of the Bhakti movement, concerted attempts were made to incorporate him into the family of Siva and Parvati, without much success. The earliest icon of the Somaskandamurthy can be seen in the first freestanding temple in Tamil Nadu, the Kailasanatha Temple in Kanchipuram, but the concept did not catch on."

While the myths of Kartikeya are different from those of Murugan, the late folklorist N Vanamamalai documents attempts at coalescing the two in an article titled 'Muruga-Skanda Inaippu' in his book Tamizhar Panpadum Thathuvamum (The Tamils' Culture and Philosophy). The son of Kotravai, the ancient Tamil mother goddess, and the spearwielding god of the iron age, Murugan as described in the bardic poetry of the early Sangam period evokes fire, blood and the sun. 'In Sangam works like Natrinai, Paripadal and Kurunthogai (dated around 300 BC-100 BC), Murugan retains his folk character, but we find allusions to stories from the northern epics,' he writes. 'There are echoes of the Mahabharata and the first mentions of Soora-vadham and the splitting of a hill. Like all myths centred on the killing of an asura, the story is drawn from northern literature.' The Pallava kings who ruled the northern parts of Tamil Nadu between the 3rd and the 9th centuries—and were instrumental in bridging Sanskrit and Tamil—and the popularity of Kalidasa's Kumarasambhava around 500 CE, further facilitated the mixing of myths. Skanda's marriage to Devasena or Devayani, the adopted daughter of Indra, and a puzzling pronouncement in the Mahabharata by Brahma, where he calls him the son of Rudra instead of Agni, become crucial to reinventing Murugan's origin myths in Tamil land.

There are references to Devayani as early as in the Thirumurugatrupadai, a late-Sangam devotional poem by Nakkiranar that celebrates Murugan's temples, his valour and beauty. And yet, to this day, in the Tamil popular mind, he is always the consort of Valli. The seafarers and fishermen of Tamil Nadu, the Paravars, consider Murugan their machaan or brother-in-law, says Joe D'Cruz, a Sahitya Akademi Award-winning Tamil writer who has documented the lives and the past of the community. "There is a forgotten lullaby that laments his second marriage to Valli, when he was already married to our girl Devayani," he says.

BJP's pre-poll alliance with AIADMK is somewhat like Murugan's arranged marriage to Devayani: it does not appeal to the Tamil imagination. Kasi Viswanathan, who comes from a long line of priests at Tiruchendur and has served at the temple for the past two decades, admits it is Valli who is the prominent consort at the temple. "In temple processions, the Lord is followed by one consort for a period of six months and then by the other for another six months. But Valli is the one by his side in the puja conducted inside the sanctum and the one who weds him the day after Soorasamharam," Viswanathan says. This year's festivities were a tepid affair, he says, with 2,000 policemen deployed and only officials and priests in attendance. Section 144 was in force in the seaside town. Pujas at the temple, the only one among the arupadai veedu (the six abodes) that is not located on a hill, are based mainly on the Kumarasuktam from the Rig Veda, although Tamil texts are also recited. Known as Tirucheeralaivai in the old Tamil world and as Jayantipuram in the Puranas, Tiruchendur is the place that inspired Subramanya Bhujanga, Adi Sankara's emotional entreaty to the lord composed in a time of ill health.

WITH THE ADVENT of the Bhakti movement, new literature on Lord Murugan thrived, excavating his origins from Sanskrit texts and marrying them with aspects of the old Tamil faith. The 15th century sage-poet Arunagirinathar alone wrote over 2,000 songs, with his Thiruppugazh anthology still reigning popular among devotees and musicians in Tamil Nadu. Arunagirinathar routinely addresses Murugan as Perumal, incorporating Vaishnavite ideas, and borrowing from the Puranas. "To Siva, you preached the fundamental mantra that predates the Vedas, while the other two of the Trinity along with thirty-three crores of devas, watched and worshipped your feet," goes one verse, evoking a scene from Skanda mythology immortalised in the sthala purana of the temple in Swamimalai near Kumbakonam. "The lord of Palani, who is a young ascetic of disproportionate wisdom, and the six-faced conqueror of Tiruchendur seated on his peacock throne with his two consorts are the most popular forms of Murugan in Tamil Nadu. But Swamimalai, where Murugan claims the guru's position and explains the meaning of the pranava mantra to his father, is special to Tamils for scoring one back on Siva," says MV Bhaskar, an art historian and epigraphist. According to Bhaskar, the word 'murugu', commonly interpreted as beauty and fragrance, can be equated with the twist found in Indus Valley clay tablets. "'Murugu' also stands for the pictogram from the Indus Valley Civilisation representing the body buried in a pot in the foetal position, with strokes for the backbone and without—according to Indus script researchers Iravatham Mahadevan and Asko Parpola," he says. Other scholars have compared Murugan to the Minoan god Velchanos and even to Dionysius.

"What sets Murugan apart from other Hindu gods is how accessible and relatable he is to the subaltern people. He is neither a minor god nor a mainstream Brahmin deity—he is related to all Tamils," says Sahitya Akademi-winning writer Cho Dharuman. "In the 20th century, Valli's wedding became a much-loved theatre performance in rural Tamil Nadu, so did kuravan kurathi attam, a folk dance. If AP Nagarajan's 1965 film Thiruvilayadal, based on the 16th century Thiruvilaiyadal Puranam, brought Murugan even closer to the mortal world, Annamalai Reddiar's Kavadi Chindu, a whole new genre of folk songs, inspired a generation of film and dance music."

"Balamurugan was the Tamils' answer to the Baby Krishna cult of north India," says S Raghuraman, a Sangam Tamil scholar. "In fact, a third of all Pillai Thamizh compositions, a genre that evokes gods, heroes and heroines as children, in medieval Tamilakam were on Murugan." The young Murugan's beauty is the standout attribute that Sangam literature dwells most on, Raghuraman says. In his 1927 work, Murugan Alladhu Azhagu (Murugan or Beauty), TV Kalyanasundaram, a pre-Independence era Tamil scholar, essayist and activist better known by his Tamil initials Thiru Vi Ka, notes that ancient Tamils equated murugu with the universally accepted characteristics of fragrance, youth, divinity and beauty. 'Only if one is iron-hearted does murugu not bloom in their hearts,' he writes. While worship of Lord Murugan remains a constant in Tamil country, channelling his glory to make the lotus bloom is a different proposition altogether.