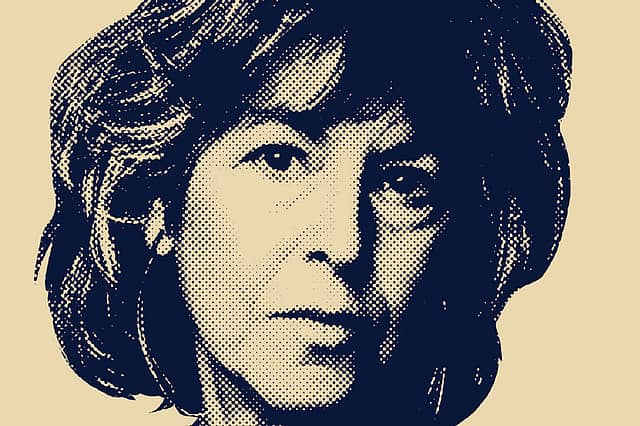

Louise Glück: Austere Notes

AFTER THE TUMULTUOUS last few years where the Nobel Prize in Literature has been beset with scandal and controversy—from having the 2018 prize postponed because the husband of one of the Nobel Committee members was accused of sexual harassment and abuse, as well as leaking the names of the winners to bettors, to the choice of the Austrian writer Peter Handke for one of the awards last year, someone who has been trailed by accusations of genocide denial for years—it was assumed that the committee would pick someone safe.

The 77-year-old American poet Louise Glück isn't just a safe choice. She is also widely considered to be among the leading practitioners of the form, pushing poetry into very personal and interesting new directions. In a career that has spanned over six decades, she has won almost all the big literary awards in the US, from the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, to the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Bollingen Prize and the National Humanities Medal. Between 2003 and 2004, she was also appointed US' Poet Laureate.

Glück's poems are, what the poet and critic Dan Chiasson calls, the 'flash bulletins from her inner life.' But while the autobiographical background is significant in her works, as Anders Olsson, the chair of the Nobel committee said while explaining their decision, "she is not to be regarded as a confessional poet. She seeks universality." Writing in The New Yorker, Chiasson says, 'Outside her poems, much noisy history has occurred, this past half century. Inside them, you find, X-rayed by an unusually analytic mind, only the kinds of thing that Emerson once said a poet needed: "day and night, house and garden, a few books, a few actions."… Glück does nothing very venturesome: she teaches…, reads mystery novels, gardens, and cooks. She has suffered more than some, less than many; she has nothing uniquely harrowing to report. If someone told you to make fifty years of poetry out of what Glück has kept on hand, you would say, No, I'm sorry, that's not possible.'

The Lean Season

31 Oct 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 45

Indians join the global craze for weight loss medications

Glück, who has written around 12 collections of poetry and a book of essays, was born in 1943 in New York. In a Washington Post article, she is quoted as having said, 'I learned to read very early, very young, and my father was fond of writing doggerel verses. So the children, the two of us, we started writing books very early. He would print them out and we would illustrate them, and many times the text was in verse.'

During high school, Glück suffered from anorexia. She is reported to have said that she sought her mother's approval, often withheld, growing up. And that the anorexia came up as a result of her efforts to assert her independence from her mother. Her condition was so severe that she nearly starved herself to death and had to spend seven years in therapy. The intense self-critical honesty in her poems owe more than a little, critics point out, to the psychoanalysis she began after being diagnosed with anorexia.

In a 2014 interview with Poets and Writers magazine, Glück talks about the importance of leading an 'authentic life' to come up with original work. 'When I was young I led the life I thought writers were supposed to lead, in which you repudiate the world,' she said. 'I just sat in Provincetown at a desk and it was ghastly—the more I sat there not writing the more I thought that I just hadn't given up the world enough. After two years of that, I came to the conclusion that I wasn't going to be a writer. So I took a teaching job in Vermont, though I had spent my life till that point thinking that real poets don't teach. But I took this job, and the minute I started teaching—the minute I had obligations in the world—I started to write again.'

Michael Schmidt, the head of Glück's UK publisher Carcanet Press, describes the Nobel committee's choice as one that is aesthetically at odds with the current age. 'She's not a cheerleader. She's in no way a voice for any cause… She's not a person trying to persuade us of anything, but helping us to explore the world we're living in,' he told The Guardian. 'She's a clarifying poet… They're really about the individual human being alive in the world, and in the language.