The Definitive Guide to Detectives

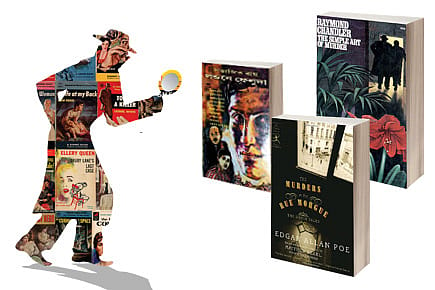

Why neat-and-clean armchair sleuths are just not as much fun as down-and-dirty alley skulks like Marlowe and Spade

It is an elementary fact of detective fiction that Sherlock Holmes is the most popular sleuth. It's hard to find a bookstore that doesn't stock the opium-smoking, violin-abusing Londoner. Even if he is a bit dated and dusty, he is still mined for inspiration by modern crime writers, because in one way or another, all fictional detectives are distantly related to Sherlock. He recently reappeared in some rather fascinating sequels, in which enterprising authors (other than his creator, Arthur Conan Doyle) brought Sherlock in closer contact with India—I am thinking, in particular, of Jamyang Norbu's The Mandala of Sherlock Holmes (1999), Vithal Rajan's Holmes of the Raj (2006), and Partha Basu's The Curious Case of 221B: The Secret Notebooks of John H Watson, MD (2009).

But honestly, a much more visionary creation is the eccentric amateur detective C Auguste Dupin, the original master of rational deduction, or 'ratiocination', who debuted in 1841—a full forty-six-and-a-half years before Sherlock Holmes. Sherlock was modelled (at least partly) on Dupin, and so it was Edgar Allan Poe who for the first time (at least in the English language) got a detective to use brainpower to crack unsolvable crime cases. The reason for Dupin's greatness lies in the fact that he doesn't just catch the crook, but also demonstrates the analytical steps that lead up to his findings. Poe's The Murders in the Rue Morgue is generally accepted as the very genesis of the detective genre, and the method described by him—close observations and the rational study of clues—is essentially what the fictional detective is concerned with even today. The rest of us are following that lead.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Subsequently, there have been scores of more or less eccentric but always very brainy brains meddling in fictional crime. Let us run through some of the highlights of the classical canon.

First and foremost, there are Hercule Poirot and Jane Marple (both created by Agatha Christie; 1920 and 1930, respectively). Poirot is interesting particularly for his longevity, because having retired from the Belgian police force in 1904, he continued to solve murders well into the 1970s, at which point he would be nearing the ripe age of 140 years (if fiction followed the laws of nature). He also set the tone for one important characteristic typical of a certain kind of fictional detective: he's one of the finickiest detectives around. Although Miss Marple is a similar super-brain, she, unlike the peripatetic Poirot who solved murders in Egypt as well as Mesopotamia, mostly works in the microcosm of St Mary Mead, a British village idyll, if it wasn't for the occasional murder—although, I'm sorry to say, the murders are as cosy as solving puzzles before the fireplace and you rarely feel the pain that death may cause.

So, the starting note for crime fiction was nice and tidy, no blood or gore. This sort of crime as a gentleman's hobby is best exemplified by Peter Wimsey (by Dorothy Sayers; 1923), who is an aristocrat with a large inheritance and an even bigger brain, plus an Oxford education, and he frequently enjoys the intellectual challenges that are provided by solving murders.

More action-based is Ellery Queen (by Ellery Queen, which was the collaborative pen name of the cousin duo Frederic Dannay and Manfred Lee; 1929), one of the first great (and bestselling) American detectives. Ellery's character was undoubtedly inspired by the above Lord Wimsey, but despite the fact that he too is a slightly snobbish puzzle-solver, the author team provided Queen with a certain psychological complexity, especially towards the 1950s when he gets increasingly troubled by his own fallibility.

We see more character development take place with the first world-famous detective by a non-English-language writer, Maigret (by Georges Simenon; 1930). He also suffered from remarkable longevity—having retired in the early 1930s, he went on to become the hero of perhaps a hundred novels and thousands of short stories, until his death was announced in 1973, at which point his fictional age was about 88 years—which nevertheless falls within the limits of a natural lifespan. One major difference between Maigret and his predecessors is that he's portrayed as an actual police inspector, and although his police work in Paris is a trifle hazy, he isn't an amateur dabbling in crime.

With Perry Mason (by Erle Stanley Gardner; 1933) the crime-solving lawyer became a global hero—another step in the development towards putting the professional on stage, and many of the mystery solutions have to do with legal procedure in one way or another.

But crime fiction was still far from getting rid of the eccentrics. The year after the first Perry Mason story, pulp literature saw the birth of that biggest brain of all, attached to such an obese detective—140 kg, the same weight as a rather big Galapagos tortoise or a typical jungle gorilla—that he doesn't ever step out to examine the crime scene. I am, as you've probably guessed, referring to Nero Wolfe (by Rex Stout; 1934).

While these are all characterful characters, they can't be taken very seriously—if you see my point. The case against big brains solving unrealistic crimes was argued by Raymond Chandler (creator of the gumshoe of gumshoes, Philip Marlowe) in his seminal essay The Simple Art of Murder (1944). It remains perhaps the most significant manifesto for crime fiction, in which Chandler challenged the whole idea of cosy mysteries that have nothing to do with actual social circumstances. Chandler points out that 'Sherlock Holmes, after all, is mostly an attitude and a few dozen lines of unforgettable dialogue.' Regarding Poirot's solution to a mystery, Chandler wrote that it is 'guaranteed to knock the keenest mind for a loop. Only a halfwit could guess it'. Following which, Chandler nominates his contemporary, Dashiell Hammett—creator of Sam Spade—as the ace performer, who 'took murder out of the Venetian vase and dropped it into the alley'.

So after a hundred-year hegemony of fat brains stuffed with grey cells, finally here was a case for detective fiction that takes into account the possibility of the reader understanding something about society and not only picking up obscure scientific facts regarding Venetian vases. This was the birth certificate of the humanised detective—with character flaws and a normal brain, somebody who could never win a quiz.

Following which we've seen genuinely interesting detectives rumbling among the dregs of human existence. One especially important development in Western crime fiction was the advent of the police procedural which lowered the level of heroic deeds, because now investigation is shown as a collective job. This genre was popularised in the 1950s through Ed McBain's novels about the 87th precinct cops—where Steve Carella doesn't hog the limelight, but is supported by a cast of hardworking policemen, including rookie Bert Kling, sarcastic Meyer Meyer and hot-headed Cotton Hawes.

The police procedural was taken further in the 1960s by my Swedish compatriots, the husband-wife team Sjöwall-Wahlöö, who wrote a series of ten social-realistic novels about the Stockholm police, where Martin Beck is a central character but, like Carella, has a large number of co-workers. In the 1990s, Henning Mankell explored the possibilities of the small-town underworld in his bestselling Wallander series, showing how Ystad with some 26,000 inhabitants could harbour countless killers. One of my favourite Swedes, however, is Kjell Eriksson, who, in the early 21st century, used the police novel to explore the complex

social structure of the university town of Uppsala—and he also created a female cop hero, Ann Lindell, who has to fight it out in a male-dominated work environment.

Then there is Lisbeth Salander—the unusually ultra-tough heroine of Stieg Larsson's Millennium Trilogy, a geek and genius, a social and mental misfit resembling the old Swedish children's book character Pippi Longstocking (who was a naughty girl with extraordinary powers), the big difference being that Salander might wipe you off the face of earth if she thinks she has a reason to.

Now that we're moving further and further away from the canon and looking at what might become the classics of the future, another favourite crime-solving woman is Kate Brannigan, a British computer expert featured in a 1990s series by the versatile Val McDermid. I think McDermid proved that although Chandler in his essay had blasted, in particular, the British crime writers of his day, the Brits will not take it lying down.

On a more offbeat track, the best—in my opinion—modern detective is the tragic Arkady Renko, a Moscow cop (created in the 1980s by Martin Cruz Smith), the amazing anti-hero of some six fabulous novels. Another path-breaker is Sonchai Jitpleecheep, a Thai police investigator, featured in four novels by John Burdett, and who converts the reader into thinking about crime and detection in a rather surprising Buddhist way.

Returning home to India, there are a couple of classic detectives, notably in Calcutta—like Byomkesh Bakshi and Feluda—and we've all enjoyed reading the stories, but strictly speaking, they belong to the pre-Chandler style. I find modern crime-busters more interesting. A personal favourite is Jaz Zadu who 'attracts beauties and bullets with equal ease' (or so Sunday Statesman wrote once upon a time), an IMFL-guzzling James Bond-character who does stuff like defusing nuclear bombs at the Kumbh Mela. The desi special agent was a 1970s creation by a writer who used the pen-name Shyam Dave, and his delightful pulp novels (such as The Kumbh Docket, The Guru Docket and The Brain Drain Docket) are sometimes found in second-hand book shops.

Other memorable homegrown heroes are the female investigator Sheila Ray in Ashok Banker's The Iron Bra (1993), and Sartaj Singh, the just-a-little corrupt cop in Sacred Games, a masterpiece of early 21st century literature by Vikram Chandra.

So, all things considered, the fictional detective has a great future ahead of him. Or her.