Bipolar Nation

Last Updated:

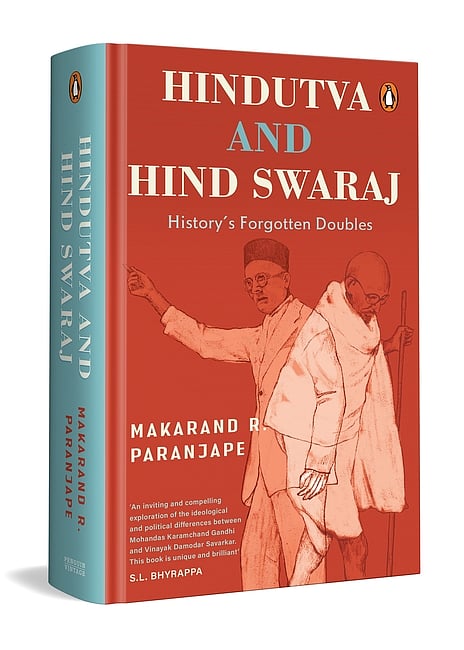

India has erred in treating Gandhi and Savarkar, or Hind Swaraj and Hindutva, as irreconcilable opposites

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

Hindutva and Hind Swaraj

aanvikshiki

The struggle could not be evaded or glossed over. Nor could it be reduced merely to supplanting or substituting the idea of Hind Swaraj with Hindutva, the new ruling ideology. Because the two were—and are—not antagonistic. Although that is how the political discourse of the day tries to portray them. Swaraj subsumes Hindutva. Hindutva without Swaraj would be severely limited in meaning, even turning dangerous

puraka

If project India that is Bharat is to succeed, old antagonisms, like wounds, cannot be ignored. Partition was one gash. Can we afford more? If the answer is ‘no,’ we must return to old antagonisms. Between Hindus and their others. But, more importantly, between Hindus and Hindus. Or, to be more specific, the antagonism between Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Vinayak Damodar Savarkar