Movie Review: Cover-Up: A Laura Poitras film starring Seymour Hersh

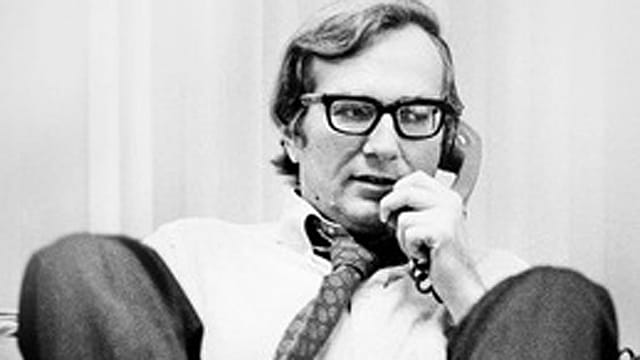

'Cover-Up', the new documentary on legendary investigative journalist Seymour Hersh by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, digs deeper than the 88-year-old author’s great scoops and exposes that include American brutalities during the Vietnam War, controversies around the late American President Richard Nixon during the Watergate scandal, Henry Kissinger’s alleged crimes against humanity, US designs on Latin America, torture at the Abu Ghraib prison near Baghdad in Iraq, the war on terror, political assassinations, his Substack pieces on Gaza, the Nord Stream pipeline explosions, the Russia-Ukraine war and so on.

The film was launched globally on Netflix on 26 December.

The documentary starts with the Dugway Proving Grounds, one of the bases for America’s chemical and biological warfare in western Utah, where the sheep start dying on a Sunday in the late 1960s and by Monday 6,000 of them perish while shepherds and their families contract stomach flu. The incident was hushed up until Hersh breaks the story -- he is also shown speaking on TV about the leakage that the government didn’t want the public to know.

The story about it, titled “The Secret Arsenal”, by Hersh was carried in The New York Times on August 25, 1968.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The documentary also goes on to highlight his superlative work over the decades that followed, starting a year later, through interviews with Hersh, visuals and documents, including news clippings and video clips, from the time. A year later came Hersh’s report on the My Lai massacre, one of his most famous investigative works for which he secured a Pulitzer in 1970.

The documentary takes us through Hersh recollecting the massacre in the South Vietnamese village of My Lai of children and women in large numbers and how he had come upon a number of sources and partial news reports that suggested that those men responsible for the killings and rapes of civilians were back home in the US after a tour. He explains in the film that one of his sources told him, “That guy, Calley, I hope he goes to hell.” That was a revelation. Hersh then discovers from a news report about a veteran named Lieutenant William L Calley. He then contacts his lawyer and Calley himself for an interview. Those interactions lead him to another shooter, Private First Class Paul Meadlo, both part of the Charlie Company commanded by Captain Ernest Medina who reportedly ordered the killings. He also gets to know US Army photographer Ronald L Haeberle who had taken a picture of the massacre in the aftermath. What is heartbreaking is what Meadlo’s mother had to tell Hersh when he met her at their home: “I sent them a good boy and they made him a murderer.” Until Hersh, then 32, broke the story at the end of 1969, this massacre of innocent Vietnamese civilians by American soldiers in March 1968 was kept a secret at the behest of top-level leaders of the US.

The film puts the spotlight on Hersh’s long career for multiple publications, including the Associated Press, The New York Times, The New Yorker, and now. It also dwells in interviews with Hersh on his childhood, parents, especially his father, a Jew born in Lithuania, about his early days in Chicago where Hersh, mostly referred to as ‘Sy’ in the film, grew up. The directors speak to Hersh’s colleagues, his editor (especially Amy Davidson Sorkin of The New Yorker), his rare sources who speak on record (one such is Camille Lo Sapio who provided him with photos from the Abu Ghraib prison), his collaborators and also address the typical concerns of his critics about his sourcing.

In fact, it took Poitras, an award-winning documentary maker and journalist, 20 years to convince Hersh to make this documentary before she roped in Obenhaus, another veteran in her field, to collaborate with her. In the documentary, Hersh insists that “we (the Americans) have a culture of enormous violence. It is so brutal”. Hersh is asked the most fundamental question about his career as a writer, “Why do you keep working”. He answers, “We can't have a country that does that and looks the other way. That is why I have been sort of on the warpath ever since.”

The film is dedicated to “all those killed and denied justice and to those who resist, past and future”.

It is also a tribute to a brave man who relentlessly unearthed lies that the most powerful people on earth wanted to hide for far too long. At 88, he shows no signs of slowing down.