Newer Delhi

AS THE SUN sets on a hazy horizon, the Dholpur sandstone domes, columns and walls on the capital's Raisina Hill light up in a pinkish hue. The rest pales. "This new lighting is the only thing that has changed," says Lokesh Kumar, a native of Bulandshahr, who has been selling Kwality Wall's ice-cream on Rajpath, looking up at the elevated seats of power, almost every evening for the last 25 years, just like his father did before him for nearly 50 years. Time has stood frozen. Biting into a Cornetto in the peak of Delhi winter, walking down what was Kingsway, imagining architects Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker riding an elephant around the rocks, one wonders what it would have taken in the early 20th century to turn the wilderness into India's new capital. And what it may yet take to redevelop an architectural heritage cast in stone.

Baker wanted an architecture with the 'spirit of life and of growth, so that it may take root in the country and not prove sterile and unproductive in the generations to come', fusing the arts of the painters, sculptors and craftsmen of the Empire with the architect's to raise 'a permanent record of the history, learning and romance of India.'

Lutyens, despite his initial belief that there is no real Indian architecture, wrote in a letter to his wife Emily, as the Rashtrapati Bhavan (Viceroy's Palace) was being built: 'the big dome is going up and it is beginning to look mighty fine and I do not think it is a gentleman's house, though original in that it is built in India, for India, Indian.'

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

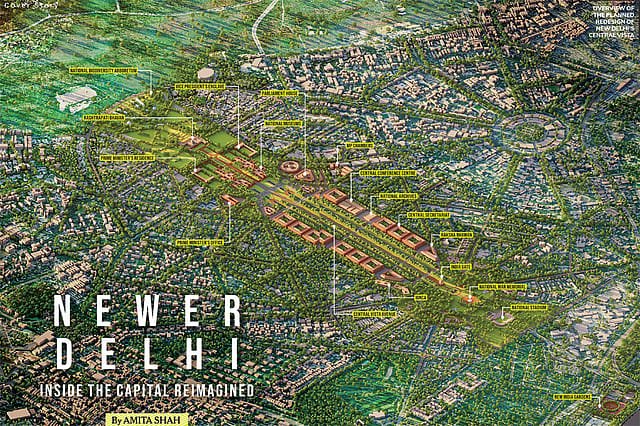

Around a century later, architect Bimal Patel pored over satellite images to conceptualise the "transformation of the Central Vista" and design a new Parliament, for which his Ahmedabad-based firm HCP Design, Planning and Management, won the bid, to give shape to Prime Minister Narendra Modi's dream. For Patel, it envisages a symbolism that goes beyond architecture. "It will now be people taking over the hill and the government will move below. It's like turning a fortress, a symbol of government power, over to the people. It's a remarkable turning around of symbolism on the 70th anniversary of the Indian Republic—the Republic is finally being established on the Central Vista, with people at the top," says Patel, referring to the Government's intent to turn North and South Blocks on Raisina Hill—where the offices of the Prime Minister, defence, home and finance ministries are located—into museums.

The government offices will be moved to 10 new buildings, forming the Central Secretariat, along the Central Vista, which runs from Rashtrapati Bhavan to Princess Park, replacing post-Independence office buildings like Shastri Bhawan, Udyog Bhawan, Nirman Bhawan and Krishi Bhawan. The new structures—rectangular with courtyards, sandstone outside and glass and steel inside—will be below the height of India Gate, the war memorial facing Raisina Hill. The National Museum will move to the old Secretariat, now the North and South Blocks which, along with Government House where the Viceroy lived, later the President's residence called Rashtrapati Bhavan, were placed on a 30-feet high plinth. Patel perceives the new plan to turn North and South Blocks into museums as the "Government's resolve to turn it over to the people."

Rashtrapati Bhavan, however, will continue to be the presidential abode. The Prime Minister's residence will be built diagonally across from Parliament, south of South Block and the vice president's residence north of North Block. Besides the North and South Blocks and the existing Parliament, the National Archives will also be restored, with an extension to be built for research. Underground, where the Metro lines cross the Central Vista, a people-mover or shuttle will connect commuters to all the offices.

Patel, for whom the focus of any architecture is "functional problem-solving", is designing a triangular Parliament to accommodate Rajya Sabha, Lok Sabha and a common lounge, "with the old and new Parliaments working as an ensemble, and the new building respecting the architectural language of the present one" with an open courtyard and sandstone walls. The new one, adjacent to the old circular one, will have offices for all MPs. In his view, Baker's original idea for Parliament was a more functional one than the one that was eventually built.

Long before Patel envisaged a triangular Parliament building, Lutyens and Baker had argued about the shape of what was then called Council House. According to New Delhi: Making of a Capital by Malvika Singh and Rudrangshu Mukherjee, with concept and visual research by Pramod Kapoor, the first plan was an equilateral triangle, the three sides or wings being approximately 1,000 feet each to house the chambers—Legislative Assembly, the Council of State and the Chamber of Princes—linked to a central imposing dome that would filter the light through. Lutyens fought the design because he felt it jarred as an important part of the larger schematic and argued for a 'circular, colosseum design'. On January 10th, 1920, the New Capital Committee decided in favour of Lutyens' plea. When Council House, inaugurated on January 18th, 1927, was being constructed, a railway track ran through the length of the circular structure to carry material.

The two chief architects designated for designing major structures like the Government House and 'Council House (Parliament)' in the Imperial City at Delhi, at a fee of 5 per cent of the total cost under an agreement with the Secretary of State in the India Council in November 1913, had locked horns on several other architectural facets as well. According to Singh and Mukherjee, one ground for discord was which dome on Raisina Hill should dominate—the ones on the Secretariat or the Government House. In another letter to his wife, Lutyens reflected his disappointment saying Baker had designed the levels in a way that Government House would not be visible from the Great Place (Vijay Chowk).

'In the end, Baker won on the issue of the gradient. Government House was hidden from view with only its dome visible till one reached the top of Raisina Hill. It worked well for the democratic rule that was to follow post 1947. The President, the titular head of India, was housed at Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Prime Minister with his cabinet began to rule from the Secretariat buildings. The latter represented the people and were dominant in placement. The Presidential office and residence were to be, on the other hand, imposing and ceremonial,' says the book.

NEW DELHI WAS born of the pangs of conflict, debate and criticism at every step— from the shifting of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi to the selection of the site, design, location, costs and timeline. The city, built on the outskirts of Delhi's seventh city—Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan's Shahjahanabad—less than two decades before the end of British rule, was taken over in 1947. Patel believes that Indians appropriated it partly because there was enough in the architecture, an Indo-Saracenic style which is a combination of Indian and European, to make it their own. Lutyens and Baker used Indian features like carved elephants, 'chhatris (small domed pavilions)', chajjas (protruding roofs), carved stone jaalis. In the Government House complex, where Louis Mountbatten was the last Viceroy to stay, Lutyens designed the Mughal Gardens over 13 acres with roses, marigold and other flowers.

Denying the claims of a 1923 article ('Delhi's Costly Glories' published in The Morning Post, London) that £20,000,000 had been spent on New Delhi till then, Lutyens wrote to the editor saying that the expenditure till March 31st, 1923 would be £5,600,000 and the total expenditure, including this figure, was estimated at £8,600,000.

In 1930, a year before the inaugural ceremony of India's 'Imperial Capital', Baker wrote in The Times, London, about the construction on Raisina Hill: 'Twenty feet of the rock that was 50 feet high had to be blasted away so that a 30 feet platform might be formed with a redstone wall built around it, comparable to the great platform base of the Persepolis, on which Darius lifted up the privileged royal enclosure in enjoyment of the view and air above the city below. On this are placed the central buildings, the Secretariat in two detached blocks, and the Viceroy's House.' He also said the principle underlying the architects' designs had been to weave into the fabric of the more elemental and universal forms of architecture the threads of such Indian traditional shapes and features as were compatible with the nature and use of the buildings.

With the buildings now nearly 100 years old, the Modi Government has drawn up seven objectives for the Central Vista project—modernising Parliament's facilities; consolidating, rationalising and synergising government functioning; providing adequate facilities for the Vice President and Prime Minister; refurbishing and better equipping the Central Vista avenue; strengthening cultural institutions in the Central Vista; commemorating 75 years of India's independence; and, a large complex project that can be executed proficiently and speedily. "I don't think Delhi has got this kind of attention for a long time. I knew something was on for some time. The Prime Minister had already applied his mind. He had looked at the Central Vista structures in other cities like DC. I inherited a lot of big maps and photographs. So obviously, he had been getting inputs from various embassies or individuals he had spoken to," says Union Minister for Housing and Urban Affairs Hardeep Singh Puri.

He, however, claims that at the heart of it all is effective space utilisation. "These buildings were constructed between 1911 and 1927. Usage was shaped by prevailing realities at that time. We lapped them up. We took them over in 1947 and put them to our use. But the fact is they are more than 100 years old. They are not energy-efficient. Some are not built to seismic requirements of Delhi, which in seismic categorisation has moved from two to four."

Puri, who describes himself as a quintessential Delhiwala, lived as a diplomat in cities like Tokyo, London, Geneva and New York, and wants the city to compare with them by virtue of ease of living and more than that, stand out for its architecture, culture and heritage. The Government intends to take forward the architecture left behind by Lutyens and Baker. "All the iconic heritage buildings will remain. We have inherited splendid architecture. We need to build on it, strengthen and enrich it, not repudiate it… Lutyens may have been a British architect, but there is an Indian extension into it. Obviously, an Indian imprint comes into it as you go along," he says. In the new building, with more spacious seating arrangement, Lok Sabha will have a capacity of over 900. So, it can be used for joint sittings, which are held just twice a year. The new Parliament project is expected to be completed in 2022 and the rest by 2024.

Shuttling between Ahmedabad and Delhi, Patel is racing against his challenging timeline. His final draft for the new Parliament House, which has to be built by 2022, needs to be ready by March-April this year. Given the number of stakeholders, size and complexity of the project, the ambitious deadline is his biggest challenge. "Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants it to be a demonstration of how projects can be of the highest quality and be completed more efficiently than they normally are," he says over coffee, between meetings at Parliament House and catching a flight.

However, asked about Modi's brief for the project, Patel says the Prime Minister was mainly interested in ensuring that an office infrastructure needed for efficient functioning of government is built. "For him, it's a project of making administration more efficient by bringing all offices in one place. That, for him, is most important. Offices spread out all over Delhi do not work well, so let's ensure they all come to one place." He points out that in his previous term, Modi apparently wanted to build a Central Secretariat because in Gujarat, when he was Chief Minister, he had a very efficient complex from which government functioned. Patel's firm had designed the new office space, Swarnim Sankul, for the Gujarat government in 2011, when Modi was Chief Minister.

In Patel's architectural philosophy, good design is one wherein everything is "fit for purpose", with comfortable places to work, right technology and natural light. "Many people design buildings from the outside and the rest is fit in. We do the reverse. We look at the insides first and see what form emerges from it. It's an iterative process of looking at it both ways, but we begin from the inside." For him, the outer facade is only one of 10 functions.

He plans to keep the outer facade of stone, a combination of light sandstone on top and red sandstone at the base, in line with Lutyens' architecture. Inside the doughnut-shaped structures, the courtyard will have large windows to allow the light in. "If you look at the literature, Lutyens came here saying he would build only in British or European style that was prevalent then and wanted zero adaptation to India. He said Indian architecture had nothing to contribute. He was wrong.

Eventually, the Viceroy and others put their foot down and said elements from Indian architecture should be incorporated. What's amazing is how successfully and elegantly he managed to do this. He went around picking up forms. So the Rashtrapati Bhavan dome is more like a stupa than a regular British dome. The patterns, motifs and symbols he took from everywhere are all sort of adapted from Indian themes. I haven't met many who see this as a legacy or symbol of colonialism. At Independence, our government and people appropriated it fully." All eyes are on Patel, but he is also the man in the eye of the storm.

The Central Vista redevelopment has generated much heat from various quarters, with some calling it Modi's vanity project. A day after Patel, along with Puri, met mediapersons for an interaction on the project, a group of architects went into a huddle at the India Habitat Centre library, listing a series of questions for the Government. They divulge that such meetings are being held across cities. "The Government is moving in unseemly haste. Why this rush?" ask architects Madhav Raman and Anuj Srivastava. According to them, around 200 people from various walks of life, including nearly 50 architects, are raising concerns about the Central Vista redevelopment project. The core questions raised by them include the necessity of the project, heritage apprehensions, costs and environmental impact.

Malvika Singh, who belongs to one of the families that built New Delhi, says that in a layered city like Delhi, with multiple past capitals, a new capital could be built on another stretch of land. "Why not leave the diverse material culture that Delhi embodies to tell stories of the past for the future? Build it elsewhere and make a statement with it. Why not make the Central Vista a public space for arts, etcetera, that the world talks about?" She is of the view that a new city today will give a new generation an opportunity to bring the traditional into the modern, using a language that is organic and intrinsic to Indian civilisation. She expresses apprehensions about pulling down buildings like Shastri Bhawan, saying that architecture manifests Indian modernism. Singh, who still runs the six-decade-old monthly Seminar from her office in Connaught Place's Malhotra Building, which her maternal grandfather had bought, recalls how the shopping arcade was initially designed to have residences on the upper floors, emphasising the tradition of working and living in the same organic space.

Queensway, now Janpath, which cuts across the centre of Kingsway, now Rajpath, leads to Connaught Place. Palaces of the kings of Jaipur, Baroda, Hyderabad, Patiala and Bikaner were built at the far end of Rajpath, beyond India Gate, around the hexagon, after Viceroy and Governor-General Charles Hardinge turned down Lutyens' proposal to build their palaces along the main avenue. According to Singh's book, the demarcated land for New Delhi was mandated to accommodate the offices and residences of only those who served the Crown, shielding by that single decision, the area from the ordinary, professional citizens of Dilli. "True-blue Dilliwallahs quietly watched the skyline change as the centre of power began to prepare for the shift from Civil Lines to Raisina Hill."

HISTORIAN AND CURATOR Naman P Ahuja, who, in his work The Arts and Interiors of Rashtrapati Bhavan: Lutyens and Beyond (edited with Partha Mitter), goes into the structure's interior design and Lutyens' intervention to minute details, questions the timing of the Central Vista project in the light of costs to the exchequer: "Even when Lutyens got the project, there were huge controversies at every step. A lot of debate went on. One of the main issues raised was taxpayers' money. The seat of the Empire became a symbol of the oppression of the people. Do we want to go down that road again? State the intention with which the redevelopment is taking place clearly, assess whether that intention is valid at all, or do we actually need something else, and then see if it is being met in the best possible way." While Ahuja admits that change was inevitable, he says it requires more debate and consultation on cost-benefit analysis, electricity requirements, design, aesthetics, carbon neutrality and public spaces.

Patel insists that public space will be expanded, not reduced, saying that the construction of new buildings will be confined to within currently fenced government compounds, and those that have crept beyond the fences will be pushed back.

The Government's bidding process, through which Patel—a Padma Shri awardee associated with the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor and Sabarmati Riverfront projects—was awarded the Central Vista contract, has drawn flak. According to Puri, a design competition was held through a global tender and of the 27 companies that had applied, an Indian firm won.

Patel prefers not to react to the criticism. "I have done a large number of public projects and the way public discourse is structured, if you don't shut out negativity, you cannot focus on the work." His initial sketch, done for the CPWD competition, came out in the public domain and added to apprehensions about the project. He says that it was just a sketch for the jury and is not to be taken literally.

He sees himself as a professional more than an artist. "Many architects see themselves as artists, in which case the client's priorities become less important. Their own agenda as artists becomes supreme. I am not like that."

Among the architects who have worked in Delhi, Patel is inspired by Joseph Allen Stein, who designed the India International Centre and the Triveni Sangam, and by Habib Rahman, who designed the Rabindra Bhavan and World Health Organization building in the capital in the early 1960s.

Rahman was brought by Jawaharlal Nehru to Delhi in 1953 after the latter had liked the Gandhi Ghat at Barrackpore near Calcutta which Rahman had designed. In an interview to Malay Chatterjee in 1989, Rahman recalled that Nehru, who had set up a Central Vista Committee in 1959, was disturbed by the developments along the Central Vista. "He said in the interview that Nehru was apprehensive about the various bhawans, but was told that the designs had been finalised and could not be altered," says his son Ram Rahman, a Delhi-based photographer.

The Delhi skyline is again set for a change, this time in a span of four years. "I was humbled. It's a rare and big honour to have such an opportunity. Initially, there was just excitement. The next morning, the immense challenge that this presents sank in," says Patel. He knows that there is no going back now. The only way is to go forward.