To Die or Not to Die

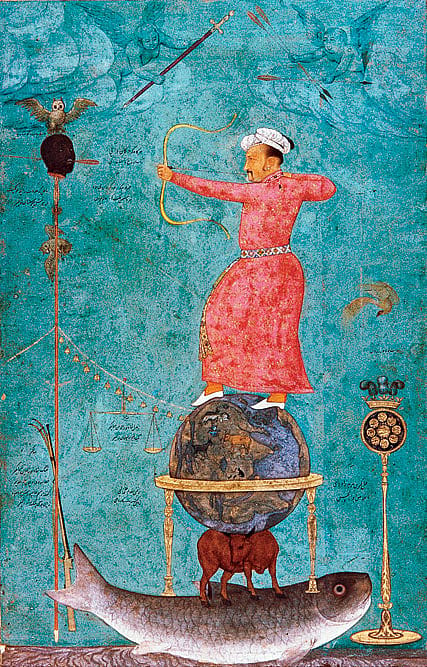

IN 1611, JAHANGIR was a seriously tormented emperor. Despite huge forces being sent to the Deccan, led by his own son Parwez, the Mughals were unable to defeat their obdurate foe, Malik Ambar. Finally, irritated beyond endurance by the spiky resistance of this talented Abyssinian general, and unable to actually overcome him in battle, Jahangir then commissioned a painting in which the emperor, rather fetchingly dressed in high-heeled slippers and a rich pink jama, shoots at the grimacing, severed head of Malik Ambar, impaled on a spike. In reality, of course, not only was Malik Ambar never killed by the Mughals, but instead he went on to found the city of Aurangabad where he enjoyed enormous prestige, entirely unruffled by Jahangir's arrows.

Described by the genteel sobriquet of 'allegorical', this painting is endlessly intriguing in the alternatives it offers to a reality that was unpalatable to Jahangir. Was it merely wish fulfilment, exorcism, or a determination that posterity be presented with a more glorious vision of the emperor's power? These are questions that the makers of the recent Bollywood movie Samrat Prithviraj seem not to have asked themselves when creating the story of a historical medieval ruler, implying a binary reading of sources quite at odds with a complicated reality.

For if Mughal record keepers were faced with conflicting requirements when creating records of Mughal history, then the task was far more challenging for the bards of the first great allies of the Mughals—the Rajputs. When Raja Bharmal of Amber first married a daughter to emperor Akbar, he catapulted the destiny of his Rajasthani hometown from one of obscurity to one of glory. His grandson Raja Man Singh became one of the greatest courtiers of Akbar and in doing so, posed the most prickly conundrum for all his panegyrists. For on the one hand, Man Singh's fortunes were inextricably linked with that of the Mughal empire, becoming one of Akbar's greatest Mughal generals. On the other hand, Man Singh was also the Hindu Raja of Amber, leader of his Kachwaha clansmen and patriarch of his 'watan jagir', his homeland. The most astonishing example of the nimble sleight of hand required to deal with these layered loyalties is to be found on the inscriptions at Rohtas fort in Bihar. After he had successfully brought Bihar into the Mughal fold in the 1590s, Raja Man Singh built an enormous palace at Rohtas fort, at the entrance to which are two separate inscriptions, one in Persian and one in Sanskrit. The Persian inscription, destined for Mughal courtiers, offers fulsome praise to Akbar, only mentioning Man Singh very humbly in his capacity as builder of the fort. The Sanskrit inscription, however, intended for Man Singh's Kachwaha clansmen as well as his Rajput peers, does not mention the Mughal emperor at all, and instead elevates Man Singh to 'Maharajadhiraja Maharaja', a veritable scrum of superlatives designating him the 'King of Kings'. Read independently, each inscription appears to make a claim that is roundly disproved by its adjoining plaque but taken together, these statements are carefully poised political acts, claiming a status aimed not only at Man Singh's kinsmen but also at other Rajput kings, and potential enemies.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Raja Man Singh's official court poet, Amrit Rai, writing in Brajbhasha, wrote a biography of Man Singh that effortlessly weaves factual events with dizzying imaginings. Writing about the defeat of Rana Pratap by Man Singh at Haldighati, the poet omits to write about the fact that Man Singh, having defeated Rana Pratap at Haldighati, failed to pursue and capture his defeated but much respected opponent, and forbade his army from pillaging and laying waste to the Rana's lands. These prosaic details of conflicting loyalties are expertly avoided altogether in the Mancarit, which presents Man Singh as the swashbuckling Rajput warrior par excellence. For Amrit Rai, this diplomatic interplay of fact and fiction, history and kavya, was what his patron would expect and applaud.

If the task was delicate enough for a poet recounting the illustrious deeds of an honourable man like Man Singh, then the work was altogether more challenging for one whose patron had committed an assassination. In the early 17th century, two discontented princes formed an unlikely and bloody friendship. Mirza Salim was growing increasingly sullen at the realisation that his father, emperor Akbar, would never consider him worthy of the Mughal throne while Bir Singh Deo of Bundela, youngest of eight sons, was similarly loath to give up the gaddi of Orccha to his elder brothers. Salim promised Bir Singh Deo he would support his cause, but in turn asked of him a most loathsome deed—the murder of Akbar's great confidant and ally, Abu'l Fazl. When the Orccha poet Keshavdas came to record his patron Bir Singh Deo's deeds in the Virsimhdevcarit, this assassination posed a most troubling quandary. For if the purpose of this genre of poetry was to celebrate the vira rasa (heroic mode), then the confounding fact was that neither were the deeds very heroic in this instance, nor were the antagonists, Abu'l Fazl and Akbar, satisfyingly demonic. And so when recounting these events, which were 'true' in the sense that Abu'l Fazl was indeed murdered by Bir Singh Deo, Keshavdas adds a passage in which his patron Bir Singh, struggling with a crise de conscience, first pleads ardently with Salim to change his mind and 'give up your anger, and make peace,' the poet implores. When this does not work, the poet goes on to eulogise Abu'l Fazl, and then describes Akbar's great grief at the murder of his old friend, showing a degree of empathy with the 'enemies' that betray the poet's conflicted feelings.

As for the Rajput state of Kotah, a long-serving ally of the Mughal Empire, when the 'true' facts of history were intolerable, they were quite simply reversed. In 1720, the valiant Kotah king Raja Bhim Singh was killed in battle fighting for the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah Rangeela, beheaded by the rebel Qilich Khan. Unable to countenance such an outcome, a famous Kota artist painted an extraordinary, monumental painting on cloth to commemorate this battle, the Battle of Pandhar. In one section of the painting, Bhim Singh is shown slaying Qilich Khan by decapitation, even though it is the exact opposite of what actually transpired, and despite the worrisome fact that Qilich Khan went on to live another 28 years, with his head firmly upon his shoulders.

This sort of cavalier disregard to what might be called 'true' facts drove British colonial officials to distraction, causing one particularly aggrieved official to rail that Indians had an 'easily excitable imagination and undisciplined historical consciousness'. But scribes like Keshavdas and Amrit Rai never did consider themselves writers of history. Though they may have recorded a few instances of well documented historical events, they were primarily writing literary documents, obeying specific literary protocols. The patron was to be praised in hyperbolic terms and indeed the very purpose of these poems was to praise the patron in eye-wateringly excessive ways. In the Kutch region, bards were meant to master the art of wakan karvun, ie the eulogising of the qualities of an exalted patron, such as a king. Flattery of the most outrageous sort was an art form, quite literally.

This is what the makers of Samrat Prithviraj perhaps failed to sufficiently recognise. The text that the movie is based on, the Brajbhasha poem Prithviraj Raso, much like the Mancarit and Virsimhdeccharit, is about how an ideal kingly life may be lived, in a world in which the old order is being constantly challenged. The question perhaps then is not when or how people died, for dying is fairly prosaic and we must all die, but rather the choices we make before we die, and the manner in which we choose to transmit the consequences of those choices to a layered posterity.

As historian Allison Busch wrote, "India did not fail to become a historical society, it is a differently-historical one." To try and translate the evidence of the past in India requires a polyphony of voices, a multiverse of realities. And while Bollywood may be accused of many things, one thing it is never in danger of being accused of is an excess of nuance.