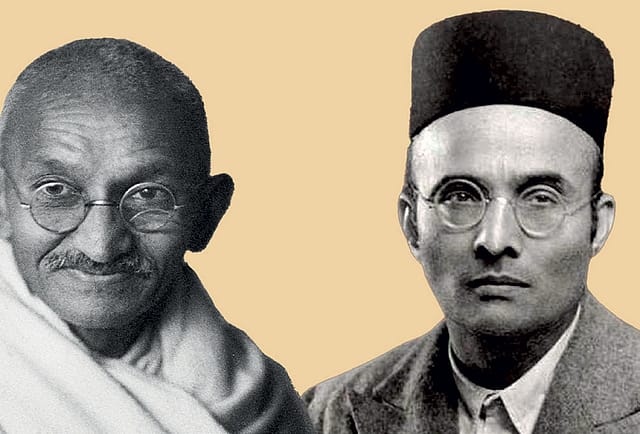

Rereading Gandhi and Savarkar

MOHANDAS KARAMCHAND GANDHI'S Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, as I mentioned in my last column (shorturl.at/cG1V9), was the other extraordinary book published in 1909. The first one, which I also discussed, was Vinayak Damodar Savarkar's The Indian War of Independence 1857.

I have written many times about Hind Swaraj (1909) and about Swaraj itself. But reading both these books again, on the eve of the 77th anniversary of India's Independence, is a somewhat uncanny experience. The two books could not be more different in their approaches to freeing India from British colonial rule.

The authors presented diametrically opposite views on how India was to achieve freedom. Gandhi advocated non-violent resistance, Savarkar armed rebellion. Both books were banned by the colonial government. Hind Swaraj was proscribed soon after reaching Indian shores in March 1910, but Savarkar's book was banned even before it was published. In fact, the ban remained in force till May 1946, right till the year before India became independent. Afterwards, in independent India, a shadow ban of sorts still continued on Savarkar's writing until recently. Now, 114 years later, these two pathbreaking books offer a unique entry point into India's present political divisions and identity crises.

The origin story of Gandhi's Hind Swaraj, also published in 1909, is also almost equally incredible as that of Savarkar's Indian War of Independence 1857.

Gandhi wrote Hind Swaraj in just 10 days, from November 13-22 aboard the SS Koldonan Castle, travelling back from England to South Africa. He wrote furiously, almost non-stop on the ship's stationary. When his right hand ached, he wrote with his left; of the 275 manuscript pages, 40 were written with the latter. Gandhi himself, as he wrote to his friend Hermann Kallenbach, believed that he had written an original work. There was no question that Hind Swaraj was an inspired work, after Gandhi's experience of illumination during his sea voyage. It is as if he had discovered the key to Swaraj.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

There was a context to Hind Swaraj that demands recounting. Gandhi was in London when Savarkar's The Indian War of Independence 1857 was clandestinely published in the Continent. In fact, in London, he had met Indian freedom advocates and revolutionaries of every stripe, including Marxists, and future advocates of Hindutva and Muslim separatism. At Shyamji Krishnavarma's India House, Gandhi encountered Savarkar too. In fact, they were both featured speakers at a Vijayadashami lunch in 1909 at India House at which Savarkar spoke after Gandhi.

Some, such as Dhananjay Keer, who wrote biographies of both Savarkar and Gandhi, even believed that Gandhi wrote Hind Swaraj in response to Savarkar's advocacy of armed revolution. Writing in his journal Young India in 1921, Gandhi recalled, "I came in contact with every known Indian anarchist in London. Their bravery impressed me, but I felt that their zeal was misguided. I felt that violence was no remedy for India's ills and that her civilization required the use of a different and higher weapon for self-protection." (shorturl.at/IU3Mw). Keer observes: "The ideological fight between Gandhi and Savarkar thus, started during the first decade of the twentieth century and continued markedly pronounced, though Savarkar was behind the bars undergoing trials and stresses of life away from the political scene. The viewpoints of Gandhi and Savarkar, not to speak of their outlook on life, were poles asunder!"

Hind Swaraj was published in the Gujarati section of Gandhi's own multilingual broadsheet, Indian Opinion. It appeared in two instalments on December 11 and 19, 1909. The following month, in January 1910, it was published as a book by Gandhi's own International Printing Press, Phoenix, Natal, in South Africa.

Copies of the Hind Swaraj reached Bombay on March 10, 1910. The authorities intercepted it and placed it in the hands of the Gujarati interpreter of the Madras High Court. Why? Because Gandhi was from Bombay; they must have thought it would be easier to prohibit the book in another presidency. On March 15, the court interpreter submitted his 21-page report in which he recommended its suppression: "Nowhere the author of the book advocates revolt or the use of physical force against the British Government in India. But he openly advocates passive resistance to subvert British supremacy. He advises all people not to cooperate with Government. If this idea takes hold of the mind of young inexperienced men, it might lead to systematic strikes among Government servants of various classes, as well as Public Works such as Railway, Post, Telegraph, etc. Surely a very dangerous thought to the safety of Government. The sooner it is suppressed the better."

That sealed the fate of the book. It was proscribed under the Customs' Act.

In March 1910, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule appeared in Gandhi's own English version as a book. It was the only one of his many publications which he himself translated from Gujarati to English. The English and other translations were, however, not banned.

Despite its somewhat contrarian and often shocking views, Hind Swaraj became world famous with passing decades as the Bible of non-violent revolution. Both Savarkar and Gandhi wanted to free India from the yoke of British imperialism and colonialism. But they disagreed radically on the means. Savarkar believed in armed revolt, Gandhi in non-violent satyagraha.

Savarkar and his followers often mocked Gandhi. Towards the end of 'The Story of this History', Joshi quotes extensively from the Free Hindusthan Special commemoration of Savarkar's book in Goshti, dated May 28, 1946: "Congressites came to power some ten years ago, they too did not raise the ban on Savarkarite literature as perhaps, it not only did not countenance but positively denounced the vagaries of the half-witted and even immoral doctrine of absolute non-violence to which the Congressites swore only verbal allegiance" (xvii). Subbarao, the author of this piece, goes on to call The Indian War of Independence 1857 "a veritable Bible by the Indian Revolutionists ever since the armed struggle", adding, "Directly and indirectly the book has influenced, animated and guided at least two generations in India in their struggles to free the Motherland" (xviii).

He gives Savarkar the credit for inspiring Subhas Chandra Bose and the Indian National Army: "Even in these days what would the Mahatmic school have called the efforts of Subhas Bose's Azad-Hind-Fouj if Savarkar's alchemy had not intervened? True. Both the 1857 and 1943 'Wars' have ended in failure for our country. But … if Savarkar had not intervened between 1857 and 1943, I am sure that the recent efforts of the Indian National Army would have been again dubbed as an Ignoble Mutiny effectively crushed by the valiant British-cum-Congress arms and armlessness" (xix). He argues that it was Savarkar who revolutionised the very word mutiny: "thanks to Savarkar's book Indian sense of a 'Mutiny' has been itself revolutionized" (ibid).

Subbarao concludes his encomium by asserting that had it not been for Savarkar, we would have forgotten all the heroes and heroines of the Great Revolt of 1857: "But the greatest value of Savarkar's book lies in its gift to the Nation of that Torch of Freedom in whose light a humble I and a thousand other Indians have our dear daughters named after Laxmibai, the Rani of Jhansi. Even Netaji Bose in a fateful hour had to form an army corps named after Rani of Jhansi. But for Savarkar's discovery of that valiant heroine, Rani of Jhansi should have been a long-forgotten 'Mutineer' of the nineteenth century". (xix)

That the revolutionary contribution to India's national struggle, especially in the 1857 Great Revolt, was not given its due by successive Congress governments cannot be denied. But would it have been erased forever had it not been for Savarkar? We need not go so far, but why should we deny Savarkar a bit of extra credit that his almost worshipful admirers want to shower on him?

114 years after they were published, both The Indian War of Independence and Hind Swaraj continue to baffle, challenge, and provoke us. India all but seems to have turned its back on the Mahatma's message. More significantly, Gandhi's critique of modernity, so uncompromisingly expounded in Hind Swaraj, seems dated and irrelevant.

Savarkar's view that 1857 was India's first war of independence is also seen as exaggerated, if not idealistic. RC Mazumdar, for example, in his centennial commemoration, had to excuse himself from a government-sponsored project because he did not agree with such a predetermined conclusion that the Ministry of Education had asked him to endorse. Instead, in his study, The Sepoy Mutiny and the Revolt of 1857, he argued that the sepoys were neither nationalistic in the modern sense, did not fight to free India from colonialism, nor enjoyed popular or widespread support from the common people across the land.

I would therefore argue that a different method, a new hermeneutics, is required to re-read both texts. In the meanwhile, the unresolved quarrel between Mahatma Gandhi and Veer Savarkar still shapes Indian politics.