‘Trump has a boyish crush on Putin,’ says Simon Sebag Montefiore

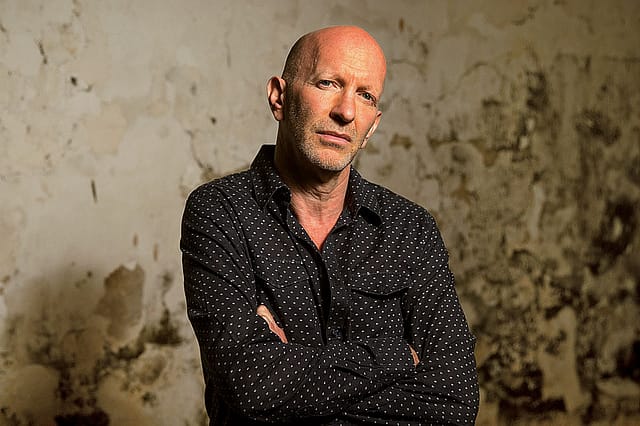

SIMON SEBAG MONTEFIORE is the kind of person who diminishes others. His repertoire of books could claim entire shelves in libraries. The 53-year-old British historian and television presenter has written more than a dozen books, spanning history, fiction and children's books. He is known for Jerusalem: The Biography (2011) which was hailed as a 'treasure trove' by the likes of Henry Kissinger and Bill Clinton. In 2016, he published The Romanovs: 1613-1918 an 'intimate story of twenty tsars and tsarinas that together formed the most successful dynasty of modern times'. He has also written the Moscow Trilogy of novels Sashenka, Red Sky at Noon and One Night in Winter. He has been translated into 48 languages, and has won numerous awards, including the Costa Biography Award for Young Stalin (2007).

His history books are 'tomes' in size but not by connotation. It is history at its best: accessible but not simplistic, academic yet vivid. The hold of Sebag's books is that they make the past contemporary; they remind us that whether it's a monarch or an elected leader, 'power is always personal' and 'in politics, ridicule is almost as dangerous as defeat'. In The Romanovs, he writes, 'Intelligent tsars understood that there was no division between their public and private lives. Their personal life, played out at court, was inevitably an extension of politics…Yet even on such a stage, the real decision-making was always shadowy, arcane and moulded by the ruler's intimate caprice (as in today's Kremlin)'. He explores such complexities of power, the public repercussions of personal beliefs and whims. His books take kings and queens, autocrats and leaders, who are all too often cast in alabaster, and make them people of flesh and blood, equal parts genius and madness. The Romanovs can at times read like Game of Thrones meets Animal Farm. In The Romanovs fathers kill sons, sons kill fathers, children are slaughtered, heads lopped off and tongues ripped out, while empresses indulge in all kinds of sex and lesbians frolic in threesomes, much of it in the name of securing power and pride.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

While the excesses of the tsars might seem relatable and far-fetched, in Jerusalem: The Biography, when he writes, 'nothing makes a place holier than the competition of another religion', he could well be writing of an Indian city like Ayodhya. In Jerusalem, he finds not just two sides, but linked and overlapping cultures and loyalties. In single individuals, he finds multiple identities, and thereby unpacks the nuances of divisions and strife that are often only understood as binaries. A historian can make sense of the world only through diversities, and he does this with authority and scholarship.

Sebag is now out with Written in History: Letters that Changed the World (Hachette India; 247 pages; Rs 599). Compared to his previous books, this is more of a breeze, and encourages readers to dip in and out of it at will. Divided into numerous categories— Love, Family, Creation, Courage, Discovery, Tourism, War, Blood, Destruction, Disaster, Friendship, Folly, Decency, Liberation, Fate, Power, Downfall and Goodbye—it allows one to turn to princes and poets, politicians and philosophers for wisdom, succour, or even humour.

In this collection, every reader will find a note that resonates with her. In their love and rage, these letters appeal to our common humanity. A 1926 letter by besotted aristocratic poet and novelist Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf reads as a 'squeal of pain' that could only have been provoked by a lover's longing. A rejection letter by TS Eliot (who was also the publisher of Faber and Faber) to George Orwell for Animal Farm can only be chortled over with the gift of hindsight. Aurangzeb's letter before death to a son of his is filled with pathos, and echoes every man's fear of having lived a meaningless life. He writes, 'I brought nothing into this world, and except the infirmities of man, carry nothing out. I have a dread for my salvation, and with what torments I may be punished.'

London-based Sebag is currently in India to attend literature festivals in Kolkata and Jaipur. He made time on his schedule to answer questions on the power of letters and the nature of power.

What inspired you to write Written in History?

I love letters. They are so immediate, so authentic, they are sparks of life and moments frozen in time. All my books are based on research on letters from archives, so I have always wanted to write this book. Here are letters from the widest variety of writers from Babur and Aurangzeb and Abd al-Rahman III and Haroun al Rashid to Churchill, Elizabeth I and Lincoln, from Leonard Cohen to Anaïs Nin, Frida Kahlo, Catherine the Great, Picasso, Michelangelo, Stalin, Mao and Mozart. Some are outrageous and shocking, erotic and delicious, brutal and vulgar, exquisite and poetical, some are letters of freedom and some are letters of repression and tragedy, some start wars and some bring peace. All humanity is there and all of them are by characters we should know and events we should understand. I hope you enjoy this book. It is a complement and companion to my big books of history such as The Romanovs and Jerusalem, Catherine the Great and Potemkin and Stalin—because some of these letters I discovered myself in the archives.

What are your own memories of letter writing and receiving? Are there some stashed away in your desk?

Yes, I love letters and of course I have many special letters saved—from my parents amongst others, and from writers and friends, and from long ago, love letters.

Could you tell us how you chose the letters for your book?

I have always kept in my head a list of the letters I wanted to put into this collection. When it came to it, the criteria were simple—they must be fascinating; they must be somehow important in human consciousness, not just politically, but also in art, sexuality, literature. I went through my library aided by my daughter Lily, aged 17, and we chose the letters together.

Can you mention one letter that nearly made it to the book but didn't, and why?

Yes, John Lennon's letter about the breakup of the Beatles almost made it, but the estate wouldn't give us permission.

As a historian who has spent hours in archives and poring over documents, correspondence, etcetera, how do you think future historians will mine the online communication of today? Do we risk losing something vital with emails?

We've lost a lot with emails and future historians won't be able to write the sort of books I have written on Stalin or Catherine the Great or the Romanovs or Jerusalem. It simply won't be possible to write such books based on thousands of intimate letters. I was so lucky to work on the archives filled with such jewels.

In an interview, you once said, "I read many wonderful novels though I now find the idea of literary fiction obsolete." Why do you find the idea of literary fiction obsolete?

As a concept, it's outdated and snobbish. Prizes in fiction are constantly won by rather bad but solemn works, read and understood by few, while masterpieces are often written by brilliant writers who were once regarded for writing Genre Fiction such as spy thrillers or fantasy or science fiction.

What has kept you hooked to Russian history over the decades?

Russia is an important country both as an empire and as a culture; it is very addictive to study. I love writing about it, I love visiting and travelling there. The ascendancy of Putin has made it essential to understand today.

What is the 'exceptional nature and character of Russian power'?

A certain sort of autocracy—see the Romanovs, see Stalin, see Catherine the Great, and then we can understand Putin.

How do you think Trump sees Putin? And how does Putin see Trump?

I think Trump has a boyish crush on Putin but also aspires to be an American tsar, an autocrat. Putin, I imagine, regards Trump as a great gift to the Russian project. No Russian leader could not be grateful for Trump's divisiveness and inconsistency. Even in the Soviet heyday of the KGB, Russian intelligence never managed to create such a schism between a US president and his security services. But Putin probably sees him also as an impulsive and erratic leader who is perhaps dangerous, even to Russia.

Given how prolific 'fake news' can be today, what according to you is the role of the historian?

As a truth teller to power, but also to advise on the lessons of the past, the dangers of the present, and the risks of the future. It's our job to find facts and write them clearly.

You were a war correspondent in the 90s. Do you ever miss being a war reporter? What do you miss about it?

It was exciting, it was a revelation and it was in some ways a very happy time for me. War is the grit of power, it is a great subject for the writer, historian, journalist or novelist. I was writing mainly about the ex- Soviet wars in the Caucasus, in Georgia, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, between 1990 and 1995, as well as Moscow. A wild time, dangerous and fascinating. After a cosy life in boarding school, then Cambridge, then investment banks, it was essential for me. I saw how power works, how empires fall.

You have described Jerusalem as 'a love letter to Jerusalem, a special thing to do.' Can you expand on that?

Jerusalem is a special city of course, the holy city, the universal one, and I always wanted to write about it. It's a very hard subject, the hardest imaginable, and no one has really done a real biography or history of the entire city, all the empires and faiths and ethnic groups from the start to now. It was a great challenge to get it right and also to catch its sacred magic as well as its cruel bitterness.

For you, how does language work differently when you are writing fiction as opposed to when you are writing non-fiction? How different are the two processes?

I love writing fiction. My novels are set in 20th century Russia and they are family stories, love stories and political thrillers with very strong women as my characters. It is very different writing fiction, totally different, and I prefer it. My three Russian novels are now all in paperback known as the Moscow Trilogy.

What are you working on right now?

A vast history book. A novel. Several TV and film scripts. And a sequel to Written in History: Letters that Changed the World that will be called Speeches that Changed the World.