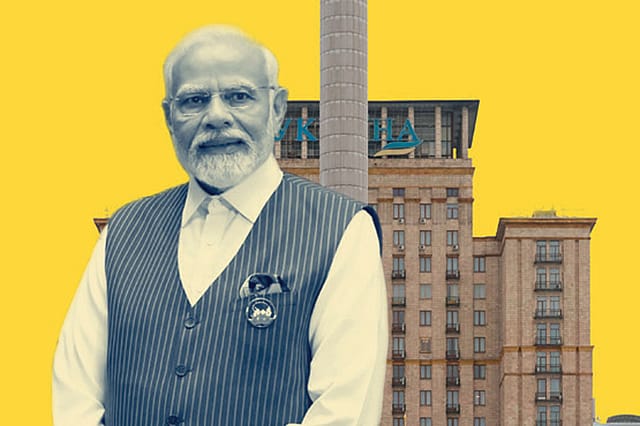

Mission to Kyiv

IN A WAR OF ATTRITION, it may take a surprise show of heroism to renew the memories of victimhood. In the Russian invasion of Ukraine that began two years ago, it is the aggressor, unforgiving as a tsar wallowing in the politics of stolen glory, who plays the victim. To invade, in his telling, was to restore justice and fairness in a manipulated history. Those tanks crossing the border in the first land war in its elemental horror after the fall of the Third Reich was a journey in time to regain the breakaway part of the homeland, or so he convinced himself. A fortnight ago, the original victim had its moment in the long nights of resistance when its troops crossed the Russian border in Kursk. Apparently, the Russian conscripts fighting for the perpetuation of Putin's fantasy surrendered at the first chance, denting Moscow's pretence of a patriotic war. What was thought to be a swift and sweet conquest by Moscow has gone on and on, vindicating the real fire of nationalism in Ukraine's defence. Kursk was a sudden reminder to the tsar about his vulnerability.

Prime Minister Modi reaches Kyiv at a time when Ukraine has sent a most urgent message to the world: this war is not for us to lose. The message matters because in Washington and elsewhere the war-funding is caught between ideology and morality: for the Right, demonisation of Russia is not an ideologically feasible answer to Ukraine's tragedy, if at all it can be called a tragedy. Putin as the ultimate autocrat steeped in grievance-powered nationalism is a figure mostly seen in the liberal texts that still care about international morality. If it was Arafat's keffiyeh and his empty holster that once symbolised the homelessness of the wandering statesman, it is the t-shirt and jeans of Zelensky that today bring out the heroism of the invaded. Modi reaches a Ukraine that, more than any other country after World War II, continues to show, at great humanitarian and territorial loss, the courage to stand up to unhinged power.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The easiest question to ask is: Can India be an honest messenger of peace without diluting its historical relationship with Russia? That is the wrong question. Maybe as wrong as the other easy phrase that crops up in the writings on international relationships: balancing act. That Modi's trip to Kyiv comes a month after his visit to Russia, which retained its special relationship with New Delhi even after the collapse of the Soviet empire and India's gradual disavowal of anti-imperialism of the Third World vintage. True: India has not 'condemned' the Russian invasion; it spoke about peace but refused to name an aggressor or sentimentalise the victim. This was in stark contrast with how India responded to the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel. We had great clarity about who was the victim—and who was the killer. Is it that, in the age of Modi, the world for India is not a collection of blocs identified by ideologies but a disparate mix of countries, each one a policy challenge by itself—national interest being the guiding spirit?

The challenge is an opportunity as well for a country which, under Modi's leadership, has gained a higher international profile. India has come a long way from the ideological constraints of non-alignment. Today it is possible to be aligned and independent. The semantics of India's response after the Russian invasion may have been too cautious for a rising power in the democratic world, but India still can be a credible messenger of peace. Russia does not have to be a baggage but an advantage. There are few leaders in the free world who can match the size of Modi's popularity, and he's undeniably the most enduring statement of democratic legitimacy in a region with constantly threatened civil societies. In Kyiv, he has a status other than being Russia's friend. He has the independence to talk peace.

What drives this freedom to choose friends without the bulwarks of a traditional alignment is a greater sense of national interest. It is this freedom that allows India to have a China policy of its own without a partnership in America's problems with Beijing. And it is not exactly equidistance that characterises India's relationship with Washington and Moscow. The distance between Delhi and Washington has been immensely reduced by India's readiness to discard inherited isms. With Moscow, it is the remains of history and pure pragmatism. On Gaza, India is no longer a subscriber to the romance of the Palestinian struggle; without forgetting past affinities, India identifies more with Israel today.

Kyiv has a story to tell any visitor from the democratic world, one about the struggle against a brutalising power that carries on with the worst habits of its lost empire. Modi, too, could not have remained untouched by it in Kyiv.