2025 In Review: Forward

MAYBE ONLY JOURNALISTS indulge in a return gaze before we step into the new year, as if the coda of the fraught yesterdays carries within it a guideline for the future. As if hope is more tangible if we can prefix it with a moral lesson from the past. So here we are, and what do we see? For a war-weary world, the most consoling image could be of a Gaza without the starved and the abandoned staring into the camera, a childhood savaged by hate as a reminder about who in the end pays the biggest price for the hate of others. In the war born from the genocidal rage of October 7, 2023, they could not have looked anywhere else for a worthy successor to the napalm girl from Vietnam and the tiny Tank Man from Tiananmen Square. In the mythologies of war and resistance, the real victims are the nameless legion who never solicited martyrdom or could never afford to define justice from the perspective of a disputed history.

Gaza lost the will for a permanent war not because slogans like From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free, reverberating from the streets of London to the campuses of America, hit the conscience of Israel, which is still the world’s most caricatured country by the global cause junkies, but because of an American president who believed not in the idealism of the moral imperium revered by his predecessor Woodrow Wilson but in the art of the deal. Hamas was left with nothing after the systematic decimation of its leadership and the neutralisation of its patrons. It was left with the Israeli hostages still alive and the prospect of managing the dead—and the fear of losing the last troglodyte in command.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Still, even in defeat, Hamas could see the glimmer of victory. It was certainly not the distant dawn of an Islamic empire, a project that gained momentum after 9/11 and the blood rites in the Levant. That was not going to happen; even the ghosts of Ayatollah and Osama, though from opposite sides of the Islamic divide, could not realise that fantasy for which the biggest death cult of modern times was sanctified by an angry god. And Hamas, too, had made its struggle more Islamist than Palestinian, and in its book, nationalism of the lost land was replaced by the scriptural manifesto for the sacred land. What Hamas did really achieve were the headlines and the photographs—and a solidarity movement spanning continents. They won the perception war despite being an organisation that did not give a damn about human lives. Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu could have gone on, adding to the armoury of Hamas propaganda. The dealmaker hoping for history’s—and the Norwegian Committee’s—approval stepped in. Hamas was denied friendly slogans. Netanyahu was denied a war that would protect his political future. And Trump did not win the Prize.

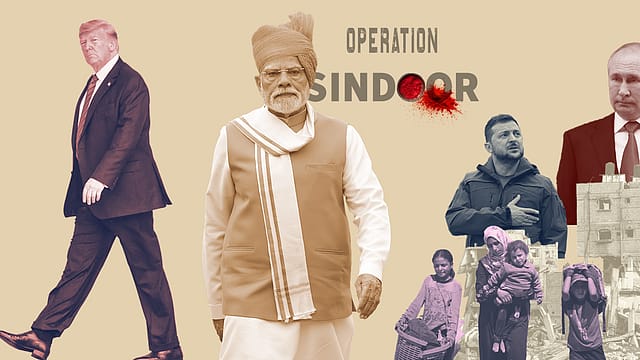

The other war raging in Ukraine defies an easy ending. It, too, is an unequal fight, but the underdog won’t give up, and the dealmaker, by nature an admirer of strength, won’t push the warmonger to the peace table. In the Middle East, the primary killer sustained its resistance against justice by arms from the enemies of Israel and exploiting the liberal campaign for the Palestinian cause—and, above all, by an imagined history of victimhood and the power of the Book. Ukraine’s tormentor, steeped in the grievances of a nationalist presiding over a shrunken home and with a firm belief that the West is undergoing an irreversible cultural degeneration, is more than an invader of a country he believes has no right to exist. He would like to see across the peace table a Ukrainian leader without a Ukraine. The man standing between the Russian with a Stalinist worldview and an American president in awe of him is the little man who won’t forego his home—or pride. And in the closing hours of 2025, the idea of home, caught between a war that was forcibly ended and a war that was allowed to go on unrestrained, provided a lesson in the unviability of moral consensus in a world where old affinities and misread ideologies get the better of our judgments.

Even as Putin stood unshaken by what he and his collaborators would dismiss as liberal sentimentalism, Trump looked lesser than his political size. The take-it-or-shove-it peacemaker has realised the limits of his methods. Then there was Trump the trade warrior. He, too, realised the limits of his imperial powers when he saw beyond the flatterers and the easily acquiesced the reality of national resolve in places like Delhi and Beijing. For India it was a choice between keeping a natural ally in good humour and standing unbowed before a bully. It chose the latter. And for Xi Jinping’s China, it was a moment for the eternal dictator to expand his domain. After all the wars Trump fought and the wars he sought to contain, at home and abroad, he looked weakened—and America didn’t look greater either. He was not alone. Elsewhere in the world, there was hardly an elected leader who deserved a Capital L. They were failing fast in managing the mandate they had won, as in London and Paris, or in reading the resentments in societies where the ownership of the nation was too precious to be left to tired ideologues.

In the evening of 2025, Western democracies may be searching for a leadership beyond the familiar templates of ideologies. India tells a different story which has not been fully grasped by those who still tend to attribute Narendra Modi’s popularity to some Hindu nationalist voodoo. More than a decade as prime minister and his conversation with India has not run out of themes, and that is because India has not ceased to reveal newer stories to a politician with an original narrative style trusted by the largest number of people in a democracy. Maybe conviction politics needed a leader who could wield power as a deliverer of social aspirations and as a destroyer of outdated ideological attitudes. He is still winning. Some leaders are allowed to enter 2026 with a better chance of being rewarded by the conversation they have started.