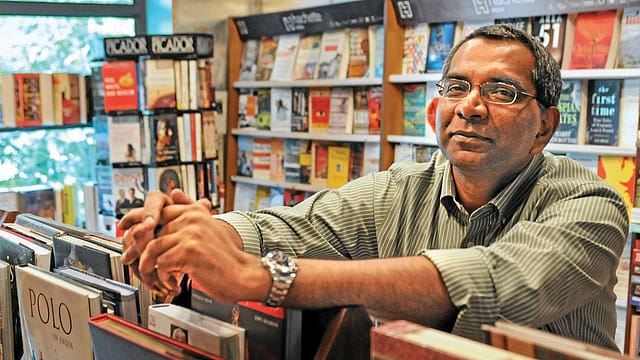

David Davidar, Publisher, novelist, and anthologist: Best of Books 2025: My Choice

One of the joys of being a publisher is that every now and again one of your friends writes a great book, a masterpiece to use that much used and abused word. It’s even better if you are the publisher of that aforesaid book but the rules of engagement of this piece prohibit me from writing about the standout books I published this past year, so let me focus on the one I didn’t. Kiran Desai is a friend of long standing, so when her new novel, The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny (Hogarth), came out I bought it immediately although I must admit I began reading it with some trepidation—would it live up to the level of excellence she had reached with her Booker Prize-winning novel, The Inheritance of Loss? I needn’t have worried. This novel is her masterpiece and should have won the Booker Prize this year—if juries weren’t so eccentric in their choices.

If you read in English, love literary novels, and haven’t been living under a rock, you will know what the book is about—a love story between two young people of Indian origin, Sonia Shah (who belongs to a family of Gujaratis “marooned in Uttar Pradesh”) and Sunny Bhatia, whose origins lie at Panchsheel Park in New Delhi. The love story has many twists and turns but it is a capacious tent that holds many marvels—the author’s trademark wit and descriptive powers, a vast family saga, darkness, light, and ideas by the dozen. Every chapter has its own magic but for me the single biggest factor that lifted the novel above the ordinary was Kiran’s exploration of a tremendously important idea that has been discussed ad nauseam but has seldom been examined with such skill, vim, and originality.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Let her explain: “The term ‘magic realism’ invented by an obsolete German scholar in the 1920s, had been seized upon by the Western world and used to describe the non-Western world, but then the non- Western world as was its inevitable downfall, became persuaded and ashamed by what the Western world thought. It refused its own myths, its own premonition dreams. It began writing in ways that were dislocated from itself… Sonia considered the enticement of white people by route of peacocks, monsoons, exotic spice bazaars—exotic to whom, you might ask—but there was legitimate concern about how India would be perceived in the larger world, that stories cheapened by proliferation, decorative outside and hollow inside, would reduce the seriousness of the nation, demean its soul, deflect attention from the compelling necessity to report on a vast unreported landscape, on millions of people with middle-class aspirations, the ordinariness of poverty. Would the dilemma vanish if the abundance of stories grew as abundant as life itself?”

If you haven’t already read the novel, read it to find the answer to that question, while being entertained and enchanted by Kiran’s gifts as a storyteller.

Kiran should have won the Booker but my second choice was David Szalay, the author of the remarkable novel, Flesh (Jonathan Cape), who did win. In many ways, the book is the exact opposite of Kiran’s mighty novel—spare, matter-of-fact, and drawn on a relatively modest canvas—but its power as a piece of fiction is undeniable, mainly because of the way in which the central character, Istvan, is drawn. We first meet him as an awkward 15-year-old in Hungary, who is seduced by an older neighbour, and then follow him through the ups and downs of his life. The material the author has chosen to work with is unremarkable, the minutiae of the life of an ordinary man, but the skill with which he uses it in the service of his fiction is extraordinary. I couldn’t put the novel down until I had finished it, and think it’s a book that I will remember.

I read an unusual amount of fiction this year, and my last two author picks in this category work in the field called genre fiction, although some of the books of one of them, Mick Herron, could hold their own with top-notch literary fiction any day.

Herron’s latest novel is entitled Clown Town (John Murray) and is quite wonderful, definitely up there with his best work, but if you have never read him before you should begin with the first book in the Slough House series (which he is best known for, especially after it was made into a TV series featuring Gary Oldman, Slow Horses. The series features a group of MI5 rejects (because of a variety of lapses, these operatives have been consigned by the British secret service to dead-end jobs in a decrepit office called Slough House—(Slough is often described as the most boring place in Britain) led by Jackson Lamb, gross, flatulent, coarse, and smart—one of the most memorable comic characters in modern fiction you will encounter. Lamb and his bunch of incompetents, who are derisively referred to as Slow Horses by the rest of British intelligence, get up to a series of shambolic adventures over the eponymous sequence of books.

When I read Slow Horses some years ago, I was immediately depressed (because I had never published anything like it) and then exhilarated (because I had never read anything like it). I guffawed, chortled, smiled, and cycled through every other variant of laughter there is because Herron is a humorous novelist of genius—on a par with PG Wodehouse (the master of masters), John Kennedy Toole, Evelyn Waugh, Sue Townsend, Joseph Heller, Douglas Adams, David Lodge, and other such luminaries.

The other vastly entertaining writer I read this year is one who works in a relatively new area of fantasy that has been dubbed “grimdark” because all its heroes, male and female, are flawed. George RR Martin is usually seen as the creator of this sub-genre of SF and Joe Abercrombie is one of its current leading lights. He has written several novels, many of them belonging to series. The one I began with, and which had me hooked, is the first novel in a new series that was published this year called The Devils (Tor Books). Who could resist the novel’s killer tag line: “When you’re headed through hell, you need the devils on your side.” Basically, the story is that of a journey through a dysfunctional landscape— Europe—with perils round every corner. The only thing that can get the heroine through this wasteland—a sort of Mad Max setting but on steroids—is a bunch of wicked men and women, vampires, werewolves, zombie knights, and so on. It’s great fun and Abercrombie has a wicked sense of humour and propels his narrative forward with dizzying pace. James Cameron has optioned the book so that should give you some idea of how good this guy is.

I read about a dozen standout non-fiction books this year, but space constraints do not permit me to talk about more than a couple. The first is called The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth (HarperCollins) by Zoë Schlanger. As the title suggests, the book is about the amazing inner lives of plants and trees— I’m a botanist by training (long lapsed, but still) yet nothing I was taught began to even scratch the surface of what this book lays bare—the “intelligence” and sophistication of the plant life that surrounds us. There have been great books about the natural world that reframe it in extraordinary ways like Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and I suspect this book will achieve such exalted status a few years from now.

And, finally, another non-fiction book that captured my imagination this year was The Zorg: A Tale of Greed and Murder that Inspired the Abolition of Slavery (St Martin’s Press) by Siddharth Kara. The Americans and the Brits do historical non-fiction for the general reader especially well and this book is a splendid addition to the genre. The Zorg was an 18th-century slave ship that in 1781 departed Africa for Jamaica with a cargo of 442 slaves. On the way, bad weather and navigation errors ensured the ship drifted way off course. As the ship began to run out of water and provisions, a diabolical decision was taken—in order to save the crew and the most valuable slaves, all the remaining slaves would be thrown overboard starting with women and children. This unspeakable act of cruelty shocked even those indifferent to the gross inhumanity of the slave trade—it became front page news, gave a fillip to the anti-slavery movement and resulted in far-reaching human rights legislation. It is the sort of narrative non-fiction book we need more of in this country.