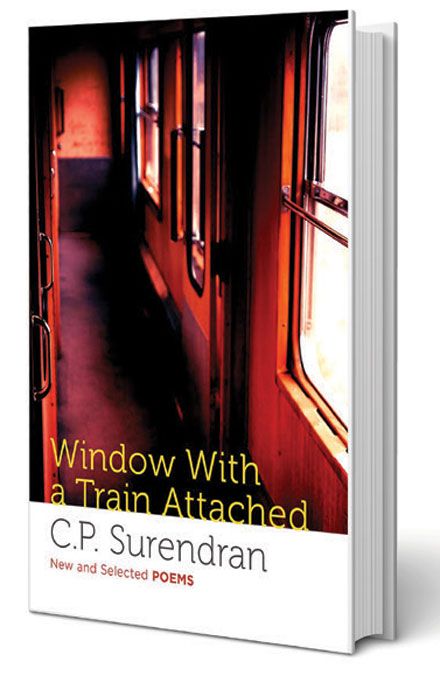

Book Review: Window With a Train Attached

CP SURENDRAN’S Window With a Train Attached moves through a landscape of absences: friends who have died, cities that have turned strange, days and nights reduced to dust. The poems are brief, pared down to the nerve. They perhaps are written with the knowledge that language cannot rescue what is lost, but that it can, for a moment, hold it to the light.

In this sixth collection, Surendran continues with the restless poise of someone who has gawked too long at the border between dream and death. In ‘Ash’, for instance, the writer documents the felling of a mango treehis father once planted: “The roots cleave the foundation of the house / They have plowed up the porch, shaking the tiles loose / Like teeth in an old man’s mouth / They advance to the study. / Searching for their man under desk and cot.” The tree must be cut. The men took on the task with an electric saw: “One said: Now that the roots are dead, / Your house is safe.” The poem holds the tension between presence and erasure in one single, unflinching motion. This is how loss gets a second life in Surendran’s poems. Slowly, systematically. The poet documents the dismantling of everything that once held meaning. The act of destruction is often made to look necessary, inevitable, as he refuses to take his eyes off. He stands amid the debris and does not walk away. Across the collection, he writes about snails and moths and sparrows and other fragile lives. Those of his friends and fellow poets, too. His attention is granular; and in that attention lies a kind of faith. The hibiscus, he tells us “is an elephant grown red in the face.” Rain “thins like last week’s gossip.” He writes of trees that “laughed white through the night,” of bougainvillea that “mixes the sun with flowers and leaves / like the sherbet that shadows drink.” The moth with “the kimono sleeves gathered from carbon spanning a million years” for wings. He calls them “vanished forests circling my lamp.”

Surendran writes as if the world, despite its decay, still deserves astonishment. He writes of caged birds that “spread their wings, the span of their hearts unease / at the one thing they are born to do, but cannot try.” And in the same breath, makes an inanimate monstrous JCB “claw down, bowing to what they hurt.”

There is something audacious in the way the poet continues to look, to record, to turn towards the light even when it blinds him. As I read I think of John Berger, who wrote that “the relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.” In Surendran’s words what we see and what we know are on either sides of the see-saw. In occasional moments of brilliance, they are held in perfect balance. “I lay myself down. Tethered to the times/ Soddening like mud, hardening like stone” he writes, “And knew we lived, as we dreamt, alone.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Reading Surendran’s Window with a Train Attached, you realise that language can arrive too late and still touch what was always here. It is poetry like this that brings to mind the viral interview with Ethan Hawke. “No one needs poetry,” Hawke says, “until their father dies, or you go to a funeral, or you lose a child, or somebody breaks your heart.” It’s true. Poetry is useless until it isn’t. And then, it becomes the only thing that makes sense. Surendran’s book belongs to that hour of the soul.