Best of Books 2025: Politics

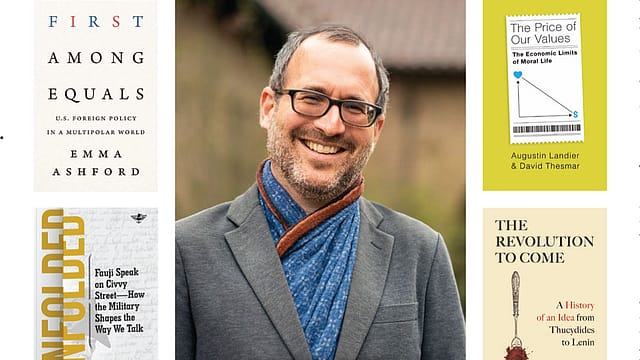

First Among Equals by Emma Ashford (Yale University Press)

From the Gulf War in 1991 to the present bombing of alleged Venezuelan “drug boats”, the US finds it hard to eschew war and coercive actions against other countries. But the results of these overseas adventures are obvious: economic costs and alienation of allies have increased manifold. These actions have been justified in a number of ways, from “democracy promotion” to the standard security threats. A realistic appreciation of dangers inherent in these entanglements from Iraq to the Balkans and from Africa to Afghanistan has been notably absent from the American academy. Emma Ashford’s book is a sober and well-argued take on these events, from the “Unipolar Moment” to the current time. The book does not make a call for “retrenchment” but a different, realistic engagement with the world.

Unfolded: Fauji Speak on Civvy Street—How the Military Shapes the Way We Talk by Pankaj P Singh (The Browser)

Ever wondered where expressions like “biting the bullet”, “bunker mentality”, “under siege” and so many other military metaphors come from? Pankaj Singh, a publisher and a man from a military lineage, has penned a delightful study of how our language has marched “in step” (another military expression) with military affairs. The book examines war literature from the West to the East in different epochs. He devotes considerable attention to the language of India’s armies that have, over millennia, experienced influences from cultures as far away as the British and the Persian, not to mention India’s own ancient military heritage. He notes the revival of civilisational memory and minting of new expressions such as Rudra Brigades, Bhairav Light Commando Battalions and Shaktiban Artillery Regiments among others and says, “To understand its significance and the linguistic reverse osmosis, we must first appreciate the extraordinary richness of India’s ancient military vocabulary.” The book is a treat for military buffs as much for wordsmiths.

2026 New Year Issue

Essays by Shashi Tharoor, Sumana Roy, Ram Madhav, Swapan Dasgupta, Carlo Pizzati, Manjari Chaturvedi, TCA Raghavan, Vinita Dawra Nangia, Rami Niranjan Desai, Shylashri Shankar, Roderick Matthews, Suvir Saran

The Price of Our Values: The Economic Limits of Moral Life by Augustin Landier and David Thesmar (University of Chicago Press)

Until India outlawed the “sale and purchase” of kidneys and other organs, the transaction between sellers and buyers, the latter often patients with life-threatening problems, had developed into a market. These transactions were morally dubious but were considered a necessary evil. The ban, effected through legislation, ended the exploitation of “sellers” but created a new set of problems. Many patients are simply unable to secure kidneys in time to survive. These issues have received considerable attention from philosophers. In 2012, Michael Sandel penned a book, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets, where he catalogued the ills of the market system and its penetration into most human relations. Now, two financial economists, Augustin Landier and David Thesmar have gently pushed back at the Sandel line. As economists they could have simply undertaken the standard optimising argument. But they are aware of the moral complexities involved in such transactions that range from sale of organs to climate change. Instead, they argue for pluralism which disentangles such issues.

The Revolution to Come: A History of an Idea from Thucydides to Lenin by Dan Edelstein (Princeton University Press)

Dan Edelstein’s book is a tour de force of the idea of Revolution from the stasis in Corcyra at the start of the Peloponnesian War in ancient Greece all the way to the “silent” democratic backsliding being witnessed in many contemporary democracies. There is a detour via Polybius, the Roman historian with an outsized effect on modern “constitutional revolutions”. Edelstein’s long story is one of disenchantment with the idea of revolution in history. That is not surprising given the bloody nature of revolutions. But one gets a feeling that the author likes revolutions but minus the bloodshed. Read the book to find out if that is possible.