In Praise of Company Artists

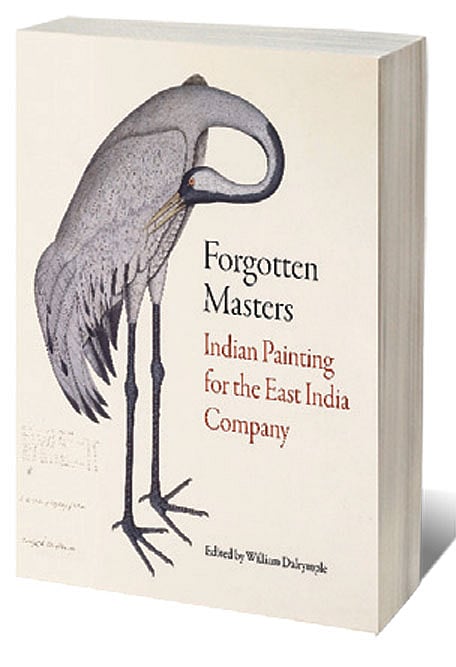

GIVEN ITS FUNCTIONAL size, reader-friendly design, and abundance of lush reproductions of rarely exhibited work, Forgotten Masters:Indian Painting for the East India Company (Bloomsbury; Rs 1,199; 192 pages) would add intrinsic value to any library. Published to coincide with ‘the first UK exhibition of works by Indian artists commissioned by British and European East India Company officials between the 1770s until 1857,’ the book is a portable iteration of the ongoing show at the Wallace Collection, London, (until 19 April) guest-curated by William Dalrymple, a ‘historian and art historian’.

Even a preliminary flipping of pages is rewarding. Details leap out—arresting uses of colour, carefully tended negative spaces that foreground compositional elements in what are primarily either ornithological or botanical studies, in certain instances, a combination of typologies, in others, even suggestive of landscape. To glimpse at them, possibly for the first time, almost two centuries after they were produced, is to encounter a genre of painting that has remained inaccessible to many Indians, given how they were made for export and are dispersed in different parts of the Western world and not just the British Library. For that reason alone, if you have the resources, this book is worth acquiring. Especially if you wish to derive pleasure from visually encountering how Indian artists at the turn of the 17th century adopted English watercolour on English Whatman watercolour paper as a medium, expanding their material vocabulary that was grounded in stone-based pigments and effecting a paradigmatic shift from the formal legacy of Mughal miniature, like colour and perspective, but modelled on English botanical still life and topographical studies, and directed by the inherently colonial gaze of their European and British patrons.

But should you choose to read critically between the lines of primarily white scholarship around the subject (the book has just two essays by Indians) or spend time reviewing their citations, you might come up short. For a book that purports to shift focus within art historical discourse, there are exclusions in citation and bibliography. If you’re inclined to seek out postcolonial-inspired, intersectional historiography (such as Partha Mitter’s Arts and Nationalism in Colonial India: 1850-1922 (1994), or his Much Maligned Monsters: History of European Reactions to Indian Art (1977)) that uncovers the nuanced nature of the hierarchical relationship between patron and commissioned artist, you could end up with copious marginalia as your reading voice seeks to register its dissent. For Dalrymple maintains the paintings were produced at what was a ‘transformative period which was far more ethnically mixed and culturally hybrid that we can imagine...’ He suppresses potential resistance to such a claim by telling us that at this moment, before India formally came under the Raj, the wills of East India Company officials show that more than a third of the British men in India were leaving all their possessions to one or more Indian wives, or to Anglo-Indian children. He shames ‘us’ if this fact surprises ‘us’ as much as it does for ‘it is as if the later Victorians succeeded in colonising not just India but also, more permanently, our imaginations, to the exclusion of all other images of the Indo-British encounter.’

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Two things stand out, the focus on imagination and the entity he refers to that collapses all readers into a collective ‘us’, therefore sidestepping the question of who constitutes the book’s intended audience. It is unclear who he is speaking to. To an Indian reader, it could read like colonialsplaining, if you are entering the book from the subjectivity of the colonised. To imagine an ‘us’ is to speak as if the project of colonisation was over, or in the past. In 2012, when I had interviewed Dalrymple for an exhibition (he had co-curated with Yuthika Sharma at Asia Society, New York, titled Princes and Painters, including 100 works by Delhi-based court artists made during 1707 to 1857) he had said, “The easy categorisation of colonial activity [within that period of 1707 to 1857] as parasitical, negative, destructive, doesn’t work.” Even today, this perspective allows for colonial washing.

In Forgotten Masters, Dalrymple is concerned with retiring the term ‘Company Painting’. He would rather we relocate the emphasis from the Company commissioners and shine the spotlight, instead, on the brilliance of its Indian creators. ‘Since Mildred Archer’s writing on the subject in the 1950s, these paintings have been known as ‘Company School’, an English translation of an Urdu term which she found being used for such works in Patna: Kampani qalam,’ he writes in the book’s inaugural essay, ‘Painting for the East India Company’. ‘The term is useful and is probably unavoidable, but it is also somewhat problematic, for it emphasises colonial patronage of these works over the artistic endeavours of the brilliant Indian artists who actually painted them; and it has led to the genre being left in something of a postcolonial limbo, largely disowned by Indians and forgotten and ignored by the descendants of their former colonial masters.’

We learn from this that the titular ‘Forgotten’ thus contains a reference to who has performed the act of forgetting. Readers do not learn about the potential reasons behind the postcolonial limbo, which is surprising given the evolving global discourse on repatriation.

An uneducated guess might point to the fact that most of the works in question exited the South Asian subcontinent and are dispersed in the West, potentially limiting Indian art historian’s access to them. To provide evidence about India ‘disowning’ the genre, he cites just one Indian critic, BN Goswamy’s neglect of it in his listing of 101 favourite Indian pictures which had only one Company commission, and his ‘brief and sketchy’ mention of it in his two-volume Masters of Indian Painting. It could have been useful to refer to Partha Mitter and Romila Thapar who have alluded to the genre’s role in orienting Western-centric discourse on India. In December 2018, Marg brought out an issue titled, ‘The Weight of a Petal: Ars Botanica,’ which dealt with ‘Company School’ paintings and featured a more inclusive stable of writers, many Indian, with an essay also by HJ Noltie, who has contributed to Forgotten Masters. This issue offers an excellent introduction to both enthusiasts and scholars, but bears no mention in Forgotten Masters.

WHILE THE WORD ‘patronage’ recurs across essays, there are few instances where the subject is fleshed out. We never learn how much these Indian ‘masters’ earned, and how unequally they earned in relation to the European counterparts who were performing similar commissions. Only in HJ Noltie’s essay, ‘Indian Export Art? The botanical drawings’ is there mention of the financial value placed on such work at the time, in reference to an auction after the early death of the first commissioner of botanical drawings from Indian artists, Dr James Kerr of Crummock. For various flowers, the selling price was Rs 1400, fish, Rs 205, water insects, Rs 118, different birds, while amphibious animals could have fetched Rs 290. Still, this is an indication of the market value, and not how much artists might have been paid. Was the remuneration sufficient? Was there no irony involved in them having to rely on European patronage because the colonial mission was complicit in hampering earnings from their conventional source of Mughal patronage?

The continued anonymity of many of these artists is rarely lamented, referred to as an act of neglect, as if it were an oversight and not a conscious act of not acknowledging subaltern labour. To dwell on such issues would mean considering the true extent of the hierarchical relationship between coloniser and colonised, and what it meant to produce work for a European gaze.

The book includes many images of excellent works that depict Indian servants serving their colonial masters, an example being Shaikh Zain Ud-Din’s Lady Impey Supervising her Household at Calcutta, made circa 1780, and currently in a private collection. In JP Losty’s ‘Sita Ram’, we are invited to imagine the subjectivity of many of these forgotten masters, and to contemplate how the compulsion towards synthesising European painting techniques with inherited Persian miniature traditions was not necessarily indicative of political will.

Noltie offers a historical reading of the term Company Art, linking its alleged roots to it being coined by the Indian collector and art historian Rai Krishnadasa as a replacement for ‘Patna Painting’, ‘along with the even more nationalistic and pejorative-sounding ‘Farangi Art’.’ He writes, ‘Indian Export Art’ might be a more fitting alternative, even though he’s not entirely convinced by the title. He adds it would ‘at least serve to change the focus from commissioner to artist and to draw attention to one unifying theme behind the diversity of styles—that to a very large extent the paintings left the country: shipped to the EIC library in Leadenhall Street in the City of London or in the baggage of their home-returning commissioners.’

In certain places, Dalrymple’s deductions contradict the scholarship of the contributing authors. For instance, he tells us that the ‘moochies’, a set of Indian artists who made such paintings, seem originally to have been leather workers ‘and so, technically, untouchable Dalits, at the very bottom of the Indian social scale’. Yet, Lucian Harris, who has contributed an essay titled ‘Bespoke: painting to order in 1830s Calcutta and Vellore’ tells us that the Moochi or moochy belonged to a leather-making caste to which many of the Tanjore artists belonged. He substantiates his claim with a citation, on page 186. The Mochi, we are told here, originally became painters because animal-hair brushes were by-products of their leather work. However, ‘despite working with animal hides the Mochis were not considered a low caste and even claimed Brahmanical descent.’ Their touch was not considered defiling and they were permitted to take part in religious ceremonies. Who is a reader to believe? Also, if the focus is meant to be shifted from the patrons to the artists, then why does the book’s editor as well as many of its contributors continue to refer to them as the ‘Fraser artists’ or ‘Hastings artists’, thus purporting a form of ownership over collaboration?

You learn that the uncomplicated use of the titular Masters should itself have been an indication of what was in store for ‘us’. The most urgent function this collection of essays performs is to remind us of the need for more intersectional scholarship that can critically re-examine the ‘Company School’ nomenclature without being complicit in the same system of erasure that facilitated both the ‘postcolonial limbo’ and the coloniser’s neglect.