An Osian of Debt

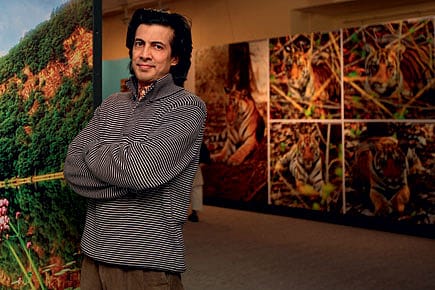

Neville Tuli on the difficulty of raising Rs 10 lakh in cash while Osian's had Rs 1,000 crore in assets, and the bad press that he gets

He hates calling it his comeback. Perhaps it's because his recent auction of Bengal art earned Rs 7.95 crore with only 55 per cent of the lots sold. Yet, the past year and a half have been exceptionally quiet for Neville Tuli, chairman of Osian's—arguably the only institution devoted to art in the country. Its ambitious ventures include an auction house (that once broke records with an Amrita Sher-Gil going for Rs 6.9 crore), a popular film festival for Asian and Arab cinema called Cinefan, a publishing house for art books, a permanent collection of Indian modern and contemporary masters, Hollywood memorabilia like Elvis' personal effects, the now infamous Rs 100-crore art fund launched in 2006, and the plan to set up a dream museum called Osianama.

The last auction that Osian's held was in June 2010. In these 18 months, there have been reports of Osian's running into debt, being sued by Sotheby's to the tune $8 million and investor confidence dipping. Tuli has been written off as a fraud, an ego-maniac and a has-been. Many of his employees left on account of unpaid salaries. Tuli chose to deal with the situation by lying low. He speaks to Open about his "time of introspection" and his problem of taking on too many things at the same time.

Q What has been happening at Osian's since it shut operations in June 2010?

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

A Our first priority is to close the art fund. That's our ethical responsibility. Unfortunately, given the state of the economy, it stayed open much longer than planned. I've tried to survive in an environment that was very negative. People didn't realise how large Osian's had become. Not just for the art we owned but also other non-profit activities (like the publishing, Cinefan, etcetera). There was pressure of the downturn, multiple outflows, and at the same time [our leverage], pressure from the media and unit holders. Some of the criticism, I felt, was unfair, but in retrospect I agree that we had become too big an entity, and the infrastructure to move things forward was just not there. I also realised that essentially, Saraswati and Lakshmi don't sit together yet, they're not willing to befriend each other.

Q So is there any hope that Saraswati and Lakshmi will see eye to eye?

A They have to, and they will. The world is moving in that direction. The world is not full of separate specialised units, it's a holistic bundle of energy. And these problems are deeper in India where the infrastructure does not exist and the scale of the problem is such that you need 50 banks to support it. The only thing India has that puts her on top of global rankings is her cultural and artistic heritage. And that is still disrespected and not monetised, which is to say that it does not exist on paper, on the balance sheet of the Government. Therefore, it doesn't exist in a manner in which it will be able to integrate with the public.

Q What about improvements at Osian's? What kind of infrastructure changes will be seen?

A Well, Osian's had become too large and too diverse. The pressure took a toll on Osian's and me because I was handling everything. But this collapse will never ever happen again. We will understand the balance between cash flow and asset ownership. At one point, we had assets worth Rs 1,000 crore but couldn't get Rs 10 lakh in cash. It was that kind of miscalculation. The biggest fall of art is when you are forced to sell it in a downturn. It has no value [then], it's junk. You can't even get 10 per cent of the value. And it's not a question of selling one painting for us. It would mean selling art worth Rs 100 crore or Rs 50 crore. And that is a lot of art, especially in a market that has shrunk to a size of just Rs 300 crore.

That dependency on having to sell assets to generate cash flow is no longer going to be there at Osian's. Look, even my worst enemies will not criticise me for my vision or idealism or conceptual frameworks. Implementation is where I faltered. Too many things ran simultaneously, without each unit getting the requisite attention.

Q A lot has been written about your debts and how Osian's singlehandedly hurt the image of the art market. With such negative press, how difficult has it been to put a new team together? I know that your workforce had shrunk to nothing.

A I have never fired anyone, I don't believe in that, but obviously when you are struggling, the confidence of your team is affected. Salaries weren't paid on time. All that did have an impact. But the loyalty of some of my staff is phenomenal. Even people who are angry with me still have that passion for Osian's and what we do here. So the core team is still there. Those who left will return once stability returns. You must understand that wealth follows idealism, it's not the other way around. So don't worry about the wealth. The point is not to lose the vision, the joy of changing something for the better. The most important thing for both an individual and institution is to maintain your core idealism. Rebuilding never takes more than two to three years. We've given 10 years to that idealism, so we can handle this phase. The negativity against Osian's is transient. It's a learning process, but tell me, which other cultural art institution in the world is even trying to do what we're doing? These 10 years at Osian's have been a teething process. How much is Shiva's blink of an eye? 26,000 years! So these are not stupid numbers that come up, these are numbers that understand the nature of evolution.

Q You think the returns from this first auction will be enough to refill and close the art fund?

A This first auction on Bengal art is the first in a set of four auctions planned in January and March 2012. These auctions will be able to close the art fund, and stabilise the auction house. My mistake was that I was trying to tackle the art fund, but ended up destabilising the auction house. I can't do that again. The first thing is to go back to our core strength, which is the auction part of the business and show the world what the market missed without us.

While we were away, the market couldn't do much because we are nearly 35 per cent of the market, not just as a seller but as a buyer too. We have bought about Rs 700 crore worth of art in the past eight years or so.

Q But while you were away, Saffronart managed to stay alive and carry on with all its auctions regularly. They didn't face a shutdown like you did.

A Saffronart is a very different model. It's a decent business model with little overheads. My model at Osian's is different. It's about changing the world. Now if you say I have delusions, I have delusions. What can one do?

Q In these past months, you never tried to defend Osian's position against reports on how much debt you owe to different auction houses, investors and art galleries. Your silence has made us believe that those humongous debts did scare you away.

A No big company in the world can move forward without debt. You must understand that the debt is minuscule compared to our asset base. That was always so. Let's say if there was Rs 50 crore of debt, Osian's had assets worth more than Rs 500 crore.

Q Did you owe $8 million to the auction house Sotheby's? What about private equity group Abraaj Capital wanting to sue you, and Christie's taking you to court?

A That's a whole lot of rubbish. The cases with Sotheby's and Christie's are settled. It's a very small amount and it's an ongoing process. Sotheby's has enough of our art and they will sell it when the time is right. Simple. You have my art, I owe you money, so go sell my art! Besides, they're holding art which is five times my amount of debt. So where's the problem?

Q That sounds too simplistic…

A Let me be very clear to you. There's bank debt at Osian's. The IDBI debt is covered by our Minerva plot (in Mumbai). The Axis Bank debt is covered by our Nariman Point office (in Mumbai). So if worse comes to worst, we can at any given point sell our properties. All the other debts are relatively small, which I believe even half an auction can solve.

Q What made you choose December 2011 for your comeback auction? There still aren't any positive indicators that the art market has recovered.

A It's been one-and-a-half years of planning. June 2010 was our last public auction. That's when I stopped, realising that having another public auction will not solve the problem. There were serious issues to tackle. So I took a step back to consolidate. And I decided to pace it out better instead of being in a rush. I could have solved the financial issue maybe in half the time, but it was not just that. It was important to keep alive the motivation that existed in the first 10 years.

Q How will you fight the scepticism of your buyers and investors?

A Scepticism is healthy. How can I not be taken to task? I happily take the blame, I have no qualms about facing humiliation or anger. It's natural because I know the journey demands it. But it's also a part of the transformation to the next level. At the end of the day, I would like to call it a collective failure. The banks need to learn, the market needs to learn and the media needs to learn. We are just one piece of the jigsaw. We need the Government to participate genuinely as well.

Q Sure. But what if the market is still not ready? You won't get your returns, you won't be able to close your fund.

A When you want to go out and change the system, you don't react to what the system is saying. You do what you think is right and take the system along with you. And there are enough people in this world who love art and who will not let us down.

Q You're not scared of another failure?

A If things fail, it doesn't make it wrong. I think it's stupid the way failure is judged today. Experimentation is at the heart of any great process. You can't tell a scientist not to experiment, and get it right the first time. Where's the need to be so harsh and ruthless for mistakes? It's okay for an institution to be held accountable where people's money is concerned. That's fair. But don't question our vision and our focus.

Q What have you sacrificed from your permanent collection to create that immediate cash flow?

A Oh, the modern and contemporary stars—the Souzas, the Tyebs, the Husains, the Swaminathans. I had to let go of about 300 good pieces of these masters at half the price. Not even a Jamini Roy or a Chittaprosad was selling. We have about 250 Chittaprosads worth Rs 12-14 crore today. But when the market was down, I couldn't even get Rs 1 crore for the entire lot. But everything else is there—all the antiquities, prints, films, posters.

Q So how is Neville Tuli different today?

A I am still as idealistic, as driven and focused about what needs to be done, but I will be careful with cash management. And I don't want to see people suffer. I was a bit ruthless before. I thought everyone must enjoy the suffering because it's part of the building process. But people are fragile. I am lucky to have a good support system, but most people don't. So I will go that extra yard to make sure my team doesn't suffer. I need to protect them.