Amnesia Hour

Somewhere, it is always the time of cholera

It is the last day of the hurricane season on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. I stand on the beach with a sense of disbelief. It's five years since Hurricane Katrina crumpled the coastline and six months since the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, but this is amnesia hour. Wiped clean of remembrance, the sky and sand make an infinitude of parallels, the sea a shining band between. In this tranquil geometry, distance is just a connecting line and if I stare long enough I might catch a glimpse of home.

"See that speck?"

I have company.

"That's Haiti."

He points to the barrier island, but I'm willing to reimagine that speck. He has sought me out, hurried over from his usual station at the finger piers in Long Beach harbour, to point out Haiti to me. The reason is not long in coming.

"They're dying like flies in Haiti. There's cholera out there."

"I heard."

"They got it from Nepal. That's in India, right?" He shakes his head lugubriously. "Wonder how the poor bastards got hit with it. India's a long way off."

The Lean Season

31 Oct 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 45

Indians join the global craze for weight loss medications

A sudden thought makes him narrow his eyes, but he's seen me around for too long to ask. He grins uneasily and walks away. "See ya around, keep safe!"

I read this morning that the cholera outbreak in Haiti has claimed more than 2,000 lives. Cholera isn't endemic to Haiti, but it is to the Indian Subcontinent. There are Nepalis in the UN Peace-keeping Force stationed at Port-au-Prince to manage the Haitians rendered homeless by the earthquake. There was a cholera outbreak in Kathmandu recently. Connect those three dots and you have a theory.

The theory gets about, and there's a riot. Cholera has been imported into Haiti. Nepali peace-keepers have been contaminating the water supply. There's even a rumour that it isn't exactly accidental. It's biowar.

Reading the news, I had a surreal vision of five men sneaking out in Hazmat suits to the water's edge—to relieve themselves.

It's not just the Nepalis who shit in the water in Haiti. Everybody does. The 1.3 million homeless send their excrement scudding into the water. But, in elegant biological parlance, their shit don't stink—because Vibrio cholerae is, don't you know, Asiatic.

I stand there, still staring at the water, but all's changed now. There's that speck, populous with the dehydrated and the dying. There's the winter sky with its icy alibi—cholera is a tropical disease. There's the sea, flashing its weaponry, but nobody's looking.

Also here I am, the Indian precedent, present and opportune—and, not just in the jaundiced eyes of the American Deep South. How can cholera not be blamed on me? On us? Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Nepali or Tibetan, people of the Subcontinent whose past is, unchangeably, India.

At this point you'll shrug and say we've been here before.

Déjà vu?

I loathe that sophism. We haven't merely been here before, we've been stuck in this moment for the last two hundred years. One hundred and ninety-five, if you want me to be precise. And until we know how we got here, we'll never get out.

The first recorded bout of epidemic cholera erupted in Bengal in 1816. By 1817, it was pandemic. Five other pandemics followed the first of 1817-23:

~ 1826-37

~ 1846-62

~ 1864-75

~ 1883-94

~ 1899-1923

Open any standard medical textbook and you'll find that the chapter on cholera starts off with the history of these pandemics. The statistics are depressing: thousands died across Europe and there were deaths in faraway New York.

The accompanying illustration is generally a world map ringed with shipping routes to show how cholera travelled out of India.

This narrative always omits one small detail.

These six pandemics killed more than 23 million Indians.

That's a detail I had to ferret out. British India kept painstaking notes on cholera, but there were certain glaring anomalies. Civilian deaths weren't counted till well into the 1860s. The seminal 19th century text on cholera was based on a study of afflicted Europeans only; 'natives' were excluded from most hospitals, and the co-existence of famine was ignored.

Despite these shortcomings, the headcount was staggering. Yet, medical textbooks say nothing about the Subcontinental history of cholera in British India.

Cholera emerged in the Indo-Gangetic basin in the early 1800s, and by the end of the century it had claimed about a third of the Subcontinent's population. Western literature records six pandemics, but India was the epicentre of cholera throughout the 19th century. The disease appeared out of nowhere, killed within a matter of hours, and was gone, leaving ghost towns in its wake. In the aftermath, there loomed a spectre Europe seldom had to contend with—starvation.

19th century India was a peripatetic montage of famine and pestilence, but here's the paradox. This battered begging bowl was the commercial capital of the British Empire, the bottomless treasury that financed the opulence of Victorian England.

Two Indias. For two peoples.

The colonial narrative of cholera is harrowing to the Indian reader. The shocked voices of British medical experts bewail our filthy habits. We're seen as a savage and ignorant race oppressed and compelled by the tyranny of a pagan and superstitious faith that denies every man his natural place in creation. An irrational people who defecate on the shores of a sacred river and then use its water for incomprehensible cleansing rituals.

All these well-meaning accounts were consumed by a central anxiety. It was embarrassing that natives should die like flies, but how much worse if India should pass on its plagues to Europe! WW Hunter's book Orissa (1872) noted: 'The squalid army of Jagannath with its rags and hair and skin freighted with infection may any year slay thousands of the most talented and beautiful of our age in Vienna, London, or Washington.'

Something had to be done to ensure that the foul miasmas of Hindoostan never tainted the pure sweet air of Europe. A series of International Sanitary Conferences were organised to address this terror. In all, 14 such conferences took place from 1851 to 1938. Within this time, the world had changed. But cholera still travelled.

Nearly seventy years after the first outbreak of epidemic cholera, Robert Koch isolated a comma-shaped bacillus from the stools of a cholera patient in Egypt. Thirty years earlier, the Italian anatomist Filippo Pacini had found bacilli in specimens from patients and cadavers in the Florence epidemic and published his Osservazioni microscopiche in December 1854.

Pacini's work was reprinted—and ignored—several times.

When Koch first observed the bacillus, he was unaware of Pacini's work in Florence. Today, Robert Koch is rarely remembered in connection with cholera. Since 1965, with delicious poetic justice, the bacillus is formally identified as Vibrio cholerae, Pacini 1854.

So what was it that made Vibrio cholerae such a globetrotter? That's a no brainer—or is it?

The obvious answer lies in those shipping routes that circled the planet in the 19th century. Cholera went from port to port. If a ship arrived from a cholera-infected port, and had no visible case of cholera on board, it was quarantined for a week. No outbreaks in these seven days meant the ship could be safely admitted to Europe.

Despite the quarantine, cholera entered Europe. Of course, then, it must be coming in with the cargo! So the cargo was disinfected. Clothes and beddings of passengers were steam sterilised—with little effect.

Whatever the explanation, infection was blamed on the miserable pilgrims of Jagannatha and Mecca. It was unthinkable that there could be any possible European source. It was, and always would be, the Asiatic cholera.

The twentieth century would be in its final decade before somebody thought outside the box.

Growing up in Calcutta in the 1960s, I was familiar with the slimy scum the city's water supply secretly carried. My mother shredded an old sari and knotted a strip around every tap in the house. I would remove the soggy cloth and shudder with delicious horror over the icky film of residue.

What was it? "Filth," said my mother, who knew biology.

"Cholera," said my dad, who didn't.

Thirty years later, I learnt he was right.

For centuries, women in the villages of Bengal have used their saris to strain water from the local stream or pond to render it potable. In the slimy residue left behind on the muslin lies the secret of cholera. This residue traps minuscule marine fauna—the zooplankton.

The humblest members of the food web are phytoplankton. They contain chlorophyll and grow in all bodies of water. Zooplankton feed off them. Tiny crustacean zooplankton called copepods flourish in environments with heavy growths of phytoplankton.

In the 1990s, Rita Colwell and Anwar ul Haq, working in Maryland, United States, and in Dhaka, Bangladesh, explored the intimate relationship between Vibrio cholerae and these tiny copepods. They found that between epidemics, Vibrio lurks piggy-backed on copepods.

This discovery has changed the way we look at cholera. Vibrio cholerae is now recognised as autochthonous. It is not an illegal immigrant, but a legitimate part of our environment. It is native to waters that contain copepods. And, almost any body of water—from an ocean to a rainwater puddle—can have copepods.

Standard laboratory cultures of samples from water bodies known to be infected often fail to grow Vibrio cholerae. This is because the bacilli are sequestered in copepods. Ultimately, large numbers of Vibrio are shed into the water. A mouthful of water from a copepod-rich source contains enough Vibrio cholerae to start off disease.

Colwell and Haq postulated that the seasonality of epidemics in Bangladesh can be correlated with zooplankton concentrations. The monsoon dilutes the salinity and reduces the temperature of the water, and makes zooplankton less active. In the months following the monsoon, phytoplankton flourish and with the glut of available food, the copepod population increases. Soon cholera breaks out.

This elegantly explains how cholera can stay dormant in endemic areas and wait for 'optimum conditions' to emerge with renewed ferocity.

So what are these conditions that optimise the pathogenicity of Vibrio cholerae and start off epidemic cholera?

To answer that, the story of cholera must be retold.

The 1816-17 reports from Jessore in Bengal suggested 'the usual epidemic' of gastroenteritis was behaving with unusual ferocity. The Medical Board of the East India Company responded to the alarm of the Civil Surgeon of Jessore with this memorable thought: 'It is probable that the consequences may in the present instance have been beneficial in correcting the influence of an overcrowded population.'

In the later years of the century, this Malthusian pronouncement was never stated so blatantly, but it remained the tacit truth of British policy.

The history of cholera in India has a dual voice, and both of them are British. One is the voice of the medical official, always conscientious, often frightened, sometimes horrified, but usually compassionate. The other is that of the British Government outraged by the poverty of a nation it has impoverished, offended by the hunger of a people it has starved, and shortchanged by the threat posed to its mercantile supremacy by India's 'ragged multitudes.'

The story of cholera is inseparable from the story of these 'ragged multitudes,' among whom we count our ancestors. They died so we may understand.

Nearly two centuries later, in the midst of another pandemic, we are still far from this understanding. We owe it to them to re-examine the story with better science.

Cholera 'emerged' in 1817 as a killer epidemic. Vibrio cholerae had always been around, leading a quiet life. And now, suddenly, it couldn't wait to try out its teeth.

It is incredible, like watching a shy gecko dart behind the bookcase and crawl out snarling with bloodied fangs, transformed into T Rex.

What could have led up to that?

In April 1815 something happened that has all but passed out of the world's memory.

Mount Tambora on Indonesia's Sunbawa Island erupted after a quiescence of 5,000 years. There were two explosions. On 5 April, the thundering of the volcano was mistaken for distant gunfire in Java, 1,200 km away. On April 10 and 11, a massive explosion shot 100 km of magma into the stratosphere. This pyroclastic ejection fell into the Indian Ocean. Gigantic clouds of ash filled the air, and blotted out the sun.

Tambora is mainly remembered for the effects it produced in distant Europe, America and Canada.

Temperatures fell. There was snow in June. Crops failed. 1816 was 'the year without a summer.' Lord Byron and his friends found their vacation at the Villa Diodati on Lake Geneva quite spoiled. Mary Shelley stayed indoors and wrote Frankenstein. John Polidori, Byron's physician, wrote The Vampyre. There were food riots in Britain, France and Switzerland. All across Europe, sunsets were spectacular, and JW Turner painted them over and over again.

These facts are common knowledge.

Less known are contemporary accounts from Indonesia. Sir Stamford Raffles, the Lieutenant Governor of Java, sent out Lieutenant Owen Phillips to Sunbawa shortly after the explosion.

This is Lieutenant Phillips' report:

'On my trip towards the western part of the island, I passed through nearly the whole of Dompo and a considerable part of Bima. The extreme misery to which the inhabitants have been reduced is shocking to behold. There were still on the road side the remains of several corpses, and the marks of where many others had been interred: the villages almost entirely deserted and the houses fallen down, the surviving inhabitants having dispersed in search of food… Since the eruption, a violent diarrhoea has prevailed in Bima, Dompo, and Sang'ir, which has carried off a great number of people. It is supposed by the natives to have been caused by drinking water which has been impregnated with ashes; and horses have also died, in great numbers, from a similar complaint.'

Thirty years later, in 1845, when Swiss biologist Henrich Zollinger climbed Tambora, the summit was still smoked. The soft ash underfoot was warm sulphur. In 2004, volcanologist Haraldur Sigurdsson excavated the remains of the lost village of Tambora buried after the 1815 explosion in 10 foot deep ash. The number of dead people on Sunbawa and surrounding islands is estimated at over 80,000. The fall of tephra destroyed arable land, and famine wiped out the countryside. A raft of logs and pyroclastic material washed up near Calcutta in 1816.

The 'violent diarrhoea' that Lieutenant Phillips ascribed to contaminated drinking water may have been the first evidence of enhanced Vibrio virulence in the area after the volcanism. This isn't just a wild guess.

Light, temperature, and salinity are all variables that regulate plankton population and activity. When vast amounts of organic matter are shed into the ocean, there's an increase in phytoplankton bloom. Copepods glut on this and revel in a frenzy of reproduction.

Copepods harbour inactive Vibrio in their chitin. Their mouthparts bristle with bacilli and their egg sacs are beaded with them. When the egg sac ruptures in water and spills eggs, it also releases a rush of Vibrio. A single copepod can harbour as many as 10,000 Vibrio. The infective dose of Vibrio cholerae is at least a million organisms, but new research suggests even this may not be a limiting factor. It's likely that during its sojourn in water, microevolution produces an increase in virulence.

What factors control this potentially dangerous change?

We don't know as yet, but a fair guess seems to be—changes in the environment.

Changes in its habitat—saline, brackish or freshwater—determine Vibrio's potential to step up virulence and cause disease.

Emergence of epidemic strains may be related to ENSO, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Seasonal variations in the Bay of Bengal noted from the earliest reports coincide with two annual peaks, both occurring when Surface Sea Temperature and Surface Sea Height are at a maximum. Perhaps the extreme conditions of the volcanic spill in 1815 caused changes in the waters of the Indian Ocean that set the scene for the emergence of cholera.

The Bay of Bengal is a semi-enclosed ocean basin. Its chief influences are the two monsoons and the massive freshwater riverine drainage from the Ganga and Brahmaputra. In addition, there are echoes of events from the distant equatorial Indian Ocean.

Between October and December, when cyclones ravage the Bay of Bengal, phytoplankton blooms intensify in the areas of cyclonic influence. Cyclonic winds stir up the waters with a vigour that brings nutrients from the deeps to the surface. When a cyclone subsides, the clear bright and washed skies drench the waters with sunshine, phytoplankton flourish, copepods glut and pullulate, and Vibrio cholerae shake off their chitinous encumbrances. The Bay of Bengal is now ready for its next epidemic of cholera.

In 1816-17, cholera emerged in an estuary. An estuary is a dynamic interface between saline and freshwater systems. Sheltered or enclosed, it still has a free connection with the sea, and is flushed with the fresh water brought in by the river.

The technical term for an increase in dissolved pollutants in a body of water—eutrophication—sounds misleadingly benign. In reality, eutrophication chokes the marine ecosystem by cutting off its oxygen supply.

In the early 1800s, the riverine waterways of Bengal were subjected to sudden change as the East India Company stepped up the traffic for trade—the Company's fleet had more than 30,000 boatmen. Tugboats and paddle-steamers soon followed. Estuaries were regularly dredged by bandalling to prevent silting. This was eutrophication on a grand scale.

Every estuary on the Subcontinent is a place of pilgrimage. All sacred places are ecologically vulnerable zones—perhaps 'sacred' is just a misreading of 'protected.' As communication became easier, more people travelled to these estuaries, which then became hot spots for cholera.

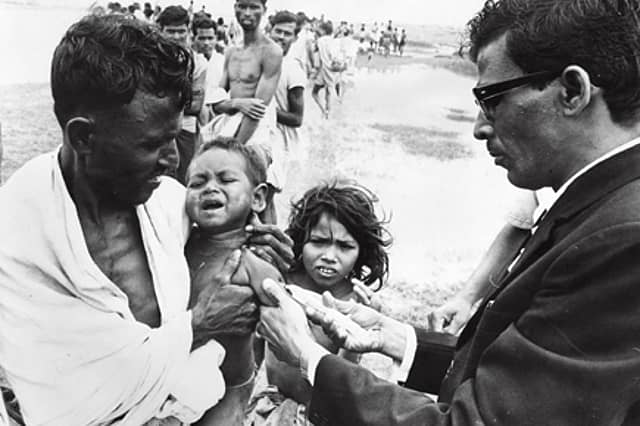

The object of Europe's revulsion in the 1800s, the pilgrim town of Puri, was like the Haiti of November 2010. In the waters clogged with human waste, zooplankton flourished, Vibrio multiplied in numbers and virulence—and cholera emerged.

The sanitary experts of British India were bewildered by the absence of an index case at each of these outbreaks at Puri—none of the pilgrims brought in cholera. Just as none of the ships from Asia docked in Bristol or Hamburg had cholera on board.

Cholera was in the water—in the Hooghly, in the Ganga, in the Bay of Bengal, in the Baltic, in the Mediterranean, in the Red Sea, and in the Caribbean—quiescent Vibrio cholerae, unnoticed until human interference colluded with climatic change. This collusion is the driver that forced cholera to emerge multifocally.

Haiti, with its vast displaced population and its misery of want and despair, was cholera waiting to happen, ever since the magnitude 7.0 Mw earthquake of Tuesday, 12 January 2010.

I'm still staring at the waters in the Gulf of Mexico and wondering. Why is it still amnesia hour?

Kalpana Swaminathan and Ishrat Syed are surgeons who write together as Kalpish Ratna. Uncertain Life and Sure Death (Maritime History Society; December 2008) is their itinerant history of epidemic disease in Bombay. Their latest novel is The Quarantine Papers (HarperCollinsIndia; January 2010).