Bloodied Bengal and Its Bhadralok

Why violence maintains its currency as a political tool in West Bengal

Few outside Bengal can even imagine this: one of the biggest killers in this state is politics! With an estimated 8,500 deaths due to political violence in less than six decades, Bengal emerges as perhaps the most politically intolerant state in the country. Add to the dead another ten thousand who have suffered grievous injuries and tens of thousands of families who've, at some point in time since the early 1950s, been forced to flee their homes and villages, and the true picture of the gory nature of politics in Bengal emerges. And for a state whose people love to flaunt their love for arts, music, prose and poetry and lay claim to the bhadralok (genteel) tag, the terribly gruesome nature of its politics presents a strange paradox.

While opinion is divided on what makes Bengal's politics so horrific, it is a fact that all political parties and leaders have blood on their hands. But the biggest share of this blame lies with the ruling Marxists who have perpetuated and even institutionalised the violence. In fact, blood started flowing in Bengal from the early 1950s when Communists started organising the poor, landless peasantry against rich landlords in what is referred to as the 'Tebhaga' movement. "The landless were not only urged to seize the farmlands they were tilling, but also to—as in typical Communist speak—annihilate the class enemy: the landed gentry. A large number of landlords and their family members were killed. There were counter-killings too. This is the genesis of the culture of violence in politics in Bengal," asserts political scientist Sibranjan Chatterjee. Others say that violence as a political strategy emerged only during the reign of Congress Chief Minister Siddhartha Shankar Ray, who oversaw killings of hundreds of Naxals and CPM activists during the early to mid-1970s. But few disagree that it was after 1977, when the CPM-led Left Front captured power in the state, that the systematic and determined subjugation of the Opposition and dissent, more often than not through gruesome methods, was perfected. This continues even today, especially in rural areas.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

That the bhadralok has a violent streak was never in doubt. Bengal was a cradle of many a 'revolutionary' even before Independence. "Bengalis have a very romantic notion of revolution that they feel is synonymous with bloodshed. Though Bengal was never dismissive of Gandhiji, it held its revolutionaries like Surya Sen, Benoy, Badal and Dinesh and Kshudiram Bose in greater esteem," Pradip Bhattacharyya, former state Congress chief, tells Open. Veteran CPI leader Manjunath Majumder concurs.

The years immediately after Independence provided a lull, but that was because the state was groping with the gargantuan problem of migration of lakhs of refugees from erstwhile East Pakistan. It was this huge influx that, in fact, led to the emergence of bloodshed in politics. "The density of population went up by 2.5 times and pressure on land became unbearable. With lakhs of peasants (who migrated from East Bengal and then East Pakistan) turning into landless labourers and clamouring for a greater share of the shrinking rural pie, the rural order had to change. Communists assumed leadership of the peasantry and led their revolt against landlords. This movement was often violent and led to many deaths," says Ajitava Raychaudhuri, economics professor at Jadavpur University. "Left politics grew out of the sense of deprivation among refugees. The sense of deprivation led to angst towards the original inhabitants of West Bengal (colloquially referred to a Ghotis, while migrants from East Bengal/Pakistan came to be known as Bangals) who were generally, and obviously, better off than the migrants. This angst manifested itself in violence, encouraged undoubtedly by the intrinsically violent nature of Left politics," says political analyst Sukumar Mitra.

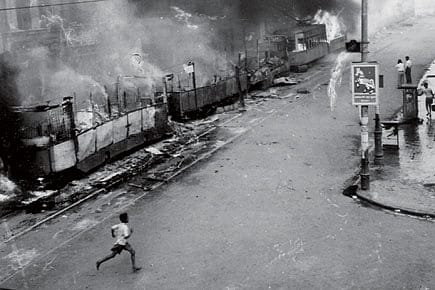

Violence in rural Bengal from the early 1950s, and from the late 1960s in urban areas, was met by brutal State repression, especially under Siddhartha Shankar Ray during the Emergency period. "More than 1,200 of our workers, including state committee member Jiban Maity, were killed, and 20,000 families of our members had to flee their homes from 1970 to 1977. That was the time of semi-fascist terror by the State machinery," says CPM state secretary Biman Bose, who flatly denies that the killings have continued, if not increased, during his party's uninterrupted reign of 32 years. The Naxalite movement also saw hundreds of people—industrialists, businessmen, doctors, professionals, academics and police and government officers—being killed before Ray unleashed the State machinery on Left radicals, who were virtually exterminated. "Those were the dark days of the 70s, days when killings and violence and disruptions became the norm. The State machinery and the ruling Congress targeted the CPM and Naxals, the CPM targeted the Congress and Naxals and the Naxals were after Congress and CPM. It was bloody mayhem. Not a day passed without violence on the streets of Calcutta. Torching of buses and trams became commonplace, while processions, rallies, demonstrations, dharnas (all Gandhian tactics, ironically) threw life out of gear. These disruptions, coupled with labour militancy and strikes, lockouts, gheraos, and assaults and killings of industrialists and their senior executives, led to flight of capital that only compounded the economic woes of an already poor people, thus fuelling more anger and more violence," Mitra elaborates.

Raychaudhuri divides the history of political violence in Bengal into two phases—pre- and post-1977. "Before 1977, it was the State machinery that was used almost exclusively by the ruling Congress to tackle the Opposition. Congressmen, generally, didn't get involved much in attacking or killing CPM workers or Naxals. But after 1977, it was the CPM cadres who started driving out the opposition and snuffing out dissent from all fora," he says. Academic Sunanda Sanyal also says that it is the CPM which initiated the culture of political violence in Bengal.

"The State repression of the 1970s cannot be defined as political violence which became the culture after 1977. The well-planned and concerted manner of eliminating all opposition was started by the CPM," Sanyal says. "The intolerance for and hatred towards political opponents was injected into the system by the CPM. Because by their very nature, Communists are intolerant of opposition and view all non-Communists as enemies who need to be annihilated. The very nature of Communist ideology is bigoted and fanatical. It is no surprise then that the CPM has been attacking, maiming and killing workers and supporters of Opposition parties," says renowned painter Suvaprasanna. However, it is not only Opposition parties that have been at the receiving end of Marxist intolerance—its own allies in the Left Front have often been targeted by the CPM. Since 1977, more than 400 supporters and workers of the RSP, CPI and Forward Bloc have been killed by CPM goons. "The CPM has always been hegemonic, trying to capture all political space. At least 200 of our workers have been killed in the last 32 years," a senior RSP leader, who's also a Cabinet minister, tells Open.

Congress leaders say that at least 1,500 of their workers and supporters have been killed in Bengal by CPM goons since the 1970s. The casualties in Trinamool ranks are even higher—an estimated 2,000 'exterminated' by Marxists over the past 12 years and thousands more displaced from their homes. Perhaps one of the most chilling examples of Marxist-induced political violence in Bengal occurred in 1969 at Sainbari village in Burdwan district, where CPM activists beheaded a young Congress supporter and smeared his widowed mother with his blood! Incidentally, the prime accused who was also convicted of the murder is now a CPM central committee member. "Thousands of such horrific killings have taken place all over Bengal and are continuing even now. We saw what happened in Nandigram where women were raped in front of their sons and then beheaded," says Sanyal.

"The CPM's culture and practice of disallowing any space to opposition and its propensity to dominate in all possible forums to perpetuate its all-pervasive and absolute influence in all spheres, institutions and aspects of life, has result in a complete undermining of the democratic process in Bengal," Raychaudhuri adds.

But violence begets violence. It is the turn of Comrades to get killed now in Bengal's western districts by Maoists. With Marxists facing one electoral rout after another, Trinamool and Congress workers who've suffered in silence may not pull their punches any longer. And blood will continue to flow in Bengal.