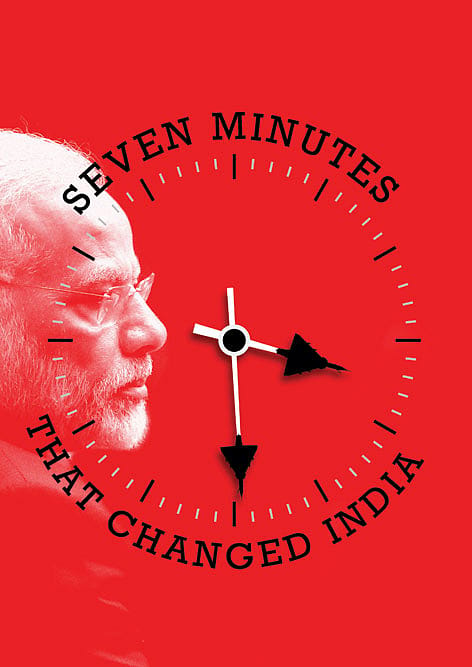

Seven Minutes That Changed India

ON FEBRUARY 24TH, 10 DAYS after the Pulwama suicide attack that killed more than 40 CRPF men and two days before the pre-dawn air strike by the Indian Air Force (IAF) on the Balakot camp of the Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) deep inside Pakistan, Narendra Modi sat staring into the distance with a deadpan expression when his National Security Advisor Ajit Doval walked in to 7 Lok Kalyan Marg, the official residence of the Prime Minister of India. Doval immediately told the Prime Minister that the IAF has a "perfect" plan. The two went into a huddle and shortly thereafter, Modi summoned IAF Chief BS Dhanoa to his home. "We can do a precision-targeted air strike on the JeM camp at Balakot and return in seven minutes flat," the IAF chief said in a measured tone as the Prime Minister and Doval listened.

That meeting was destined to change Indian strategy regarding Pakistan forever. So did the seven-minute aerial offensive on a country that allegedly shelters the JeM, the terror- outfit which claimed responsibility for the Valentine's Day suicide attack in Pulwama, Kashmir.

Before Dhanoa left, the Prime Minister insisted on what he thought was quintessential to the surprise IAF attack: there should be no casualty on the Indian side. The retaliation had to be on a greater scale than the 2016 Uri surgical strike, yet not big enough to give Pakistan a PR advantage on the global stage to play the victim card and undermine India's image as a responsible democracy. In short, punishment should be delivered unerringly to Pakistan, which houses and promotes JeM. It had to be lethal but not "life-threatening" for Pakistan. That was not all, the Prime Minister said. Before the operation is carried out, Indian forces had to be fully prepared and ready to hit the ground running.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Within hours, the three wings of the armed forces agreed to meet the 'requirements' and Modi gave the green signal.

The Prime Minister stayed awake on the intervening night of February 25th and February 26th and went to bed only after Doval told him that the fighter pilots of 20 Mirage 2000s had returned safely after carrying out the attack on a JeM camp at Balakot in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, home of Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan.

India also decided that the statements had to be sober, pithy and yet, crystal clear. Bureaucrats were put into action. Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale told the media that the pre-dawn air strike by the IAF inflicted "significant damage" on the fidayeen factory run by the JeM.

AS INDIA EXPECTED, the next day, Pakistan launched aerial attacks on Indian military targets along the Line of Control (LoC). The ensuing mid- air dogfight saw an IAF air warrior in a MiG-21 Bison take on a far superior Pakistani F-16. During the sortie, Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman, who manned the MiG-21, had to eject himself to safety after his aircraft was hit. He landed on Pakistani territory and was captured and paraded on a TV channel in gross violation of the Geneva Convention.

On March 3rd, Modi chaired a high-level meeting of the Cabinet Committee on Security in New Delhi attended by top ministers from the defence, foreign affairs, finance and home ministries, as well as Doval. The meeting was meant to assess the military preparedness of the armed forces amid simmering tensions between the two countries. It would also reaffirm the Modi Government's determination to give a carte blanche to the military to retaliate against any aggression made by Pakistan inside Indian territory. It was the first time since the Indo-Pak war of 1971 that any Indian Prime Minister has displayed such a resolve to take on Pakistan instead of buckling down in the face of repeated terror strikes engineered by non-state players such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and JeM.

This shift in strategy, senior officials aver, forced a rethink on the Pakistani deep state. As luck would have it, the international community sensed India's new confidence and put pressure on Islamabad to take tangible measures to rein in terror groups operating out of its territory. It was for a reason that Imran Khan stood up in parliament and announced the release of Abhinandan Varthaman "as a peace gesture".

In the days following the Balakot air strikes, Modi refused to budge from his position, which he had stated publicly after Pulwama: the time for talks with Pakistan was long over. India meant business and would take every action necessary to isolate and terror-shame Pakistan on the global stage. India also lost no time in pointing out that under the Geneva Convention, given that India had launched a "non-military, pre-emptive" strike in Balakot, Islamabad was obliged to release Varthaman within 60 hours. The telling message from the Indian Government had gone home to Islamabad: any further terror attacks on our soil will invite retaliation. Besides, Pakistan also had to face intense pressure mounted by countries such as the US, France, Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, the UK and others who goaded Islamabad to agree to take verifiable action on terror groups operating from its soil. Even China, a friend to Pakistan, asked Khan to exercise restraint.

Pakistan soon went into publicity mode and played the game of deception to perfection. After having appeared on TV on multiple occasions to address the global media, Imran Khan took other steps that were symbolic. He got the chief minister of Punjab to sack a minister in his province for uttering anti-Hindu remarks. In what was seen as a ruse of appearing transparent, Pakistan's foreign minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi in an interview to CNN's Christiane Amanpour admitted that JeM Chief Masood Azhar was in Pakistan but was too ill to move outside his house. While Pakistan denied that Azhar's brother-in-law was killed in the air strike, by March 5th it was busy putting out news of a crackdown on various terror outfits and the preventive custody of 44 of its leaders within Pakistan including Hamad Azhar, the Maulana's brother.

Such a Pakistani response was inevitable. France was preparing to pass a resolution in the UN declaring Masood Azhar a global terrorist. Following the Pulwama attack, the Modi Government had withdrawn the Most Favoured Nation status to Pakistan, hiked duty on goods from Pakistan to 200 per cent, initiated steps to restrict Islamabad's hopes of aid by approaching the Financial Action Task Force, and planned ways to force Pakistan to dilute its war on India using proxies. In fact, within days, India proved to the world that despite the nuclear threshold of the two nations, there was still space to mount pressure on Islamabad and inflict telling costs on the Pakistani state on the terror issue.

Omar Abdullah, former chief minister of J&K, in his first reaction to the Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale's press conference on the pre-dawn action, dubbed it a 'totally new ballgame'.

'We've entered a whole new paradigm with the Balakot air strike. The post-Uri strike was to avenge our losses, Balakot was a 'preemptive strike to prevent an imminent JeM attack'. Totally new ballgame,' he tweeted. Abdullah added that the attack on Balakot was 'hugely embarrassing for Pakistan'. 'Regardless of what the other side may claim was or wasn't hit, the planes crossed over, dropped their payload & flew back completely unscathed,' he wrote.

True, planning for a radical shift in India's strategy on Pakistan had been on the cards for a while. At home, the opposition continued to lash out at Modi for 'lapses' during the 2016 terror attacks in Pathankot and Uri, for his 'inability' to avenge the loss of lives among security forces and for his 'naive' policy regarding Pakistan and Jammu & Kashmir. There was also acute awareness of the concerns of the international community on a military conflagration between India and Pakistan, two nuclear power nations being drawn to the edge of war. These concerns were already translating into calls from world leaders to both the Indian and the Pakistani prime ministers, urging restraint and caution. India's options for retaliating to the Pakistani army/ISI-engineered terrorism on Indian soil, on the face of it, still appeared constrained and limited. But the Modi Government was determined to identify, plan and successfully execute a plan that would send out a warning to the Pakistan Army and the ISI. Clearly, that plan had to avoid nuclear confrontation while proving to the world that pressure could be mounted on Islamabad on every front to hold it accountable.

Pakistan's military-terror complex has been fighting a dangerous and surreptitious asymmetrical war against India for decades in a bid to weaken the country. Diplomatic, financial, security and political responses had to be worked simultaneously.

Modi began his diplomatic efforts almost immediately after Pulwama—liaising with international capitals and laying out case before them. Simultaneously, he made it clear to the armed forces that he refused to be bogged down by the threat of consequences. He wanted results. In the very first meeting with the service chiefs after the Pulwama massacre, the Prime Minister asserted that Pulwama would not go unpunished. While flagging off the Vande Bharat semi-high speed train to Varanasi from Delhi, Modi declared in his first reaction to the Pulwama massacre, "The blood of our people is boiling … Pakistan cannot weaken India through such acts and will have to pay a heavy price…. I have given the security forces complete freedom, a free hand to deal with the situation… this act of terror will not go unpunished." It was clear then that his reaction would be swift.

From February 15th, the Prime Minister did not go into any details on how the "free hand" would translate or when, despite attending public functions, until the three chiefs of the armed forces signalled their readiness to execute the Balakot operation and came up with a detailed plan of action.

For India, the decision to target Pakistan was supremely difficult for both political and diplomatic reasons. Modi was aware that should anything go wrong and should there be any loss to the security personnel involved in the operation, the goodwill earned by him in the aftermath of the Uri surgical strike would vanish overnight. The opposition parties had already begun taunting him within hours of the Pulwama attack and, despite a public promise that they would not politicise the development and would lend full support to the Government, resorted to ratcheting up their anti-Modi sloganeering in the run-up to the General Election. Congress spokesman Randeep Singh Surjewala went on air to demand that the Prime Minister avenge the sacrifice of jawans.

HAVING LEARNT FROM the surgical strike at Uri, the first thing that Pakistan did was ramp up security on the border to thwart any surprise from India. Diplomatically, the Government appeared to have little elbow room to act tough against Pakistan. It came at a time when Pakistan was back in a position to exploit the advantage that comes from being a very crucial real estate for the geo-strategic plans of nations like the US. The Trump administration is keen to call back US soldiers from Afghanistan and that is not possible until Pakistan nudges its proxies in the Taliban to the negotiating table. Russia, would have gone with China to act as a counterweight to the US. Diplomatically, it was not the right time—the circumstances and factors made the task of retaliation a very tough proposition. Identifying a pre-emptive, non-military retaliatory strike within Pakistani airspace, part of an extensive planning process, was tougher still.

Against this backdrop, the Pakistani establishment believed that Modi would stick to the traditional template and refrain from taking any major retaliatory action, given international concern over the two nuclear powers locking horns dangerously at the edge of a full-blown war. Many of them would admit their mistakes later. Writing on the options before Modi, columnist Swaminathan Aiyar wrote in The Times of India, 'The terrorist attack at Pulwama, killing 40 soldiers, provides Narendra Modi a huge but risky chance to portray himself as the toughest politician in India. Atal Bihari Vajpayee's victory in the 1999 Kargil war helped him win the next general election. Can Modi use Pulwama to do the same? He must avoid military action, which could backfire badly. Far wiser would be new forms of political theatre, similar to his 'surgical strikes' in 2016, in retaliation for the attack on our armed forces at Uri. That satisfied the public demand for action without risking dangerous escalation into an all-out war.'

Very few analysts expected that Modi would take such a risk, politically and otherwise, to give the green signal to strike targets inside a nuclear power. Analysts now maintain that the new paradigm has sent a strong message that every future attempt to pursue jihad under the nuclear shield would further weaken the Pakistani state.

The air strikes in Balakot were, undeniably, confirmation of the fact that the current dispensation in New Delhi has a muscular policy towards any provocation by Pakistan. The Government has established a new benchmark that the LoC is no longer sacrosanct and can be crossed by India in the face of any new terror attacks. On March 4th, Modi hit back at the opposition's persistent questioning of his motives with his "chun chun ke badla lete hain" (we avenge every single attack and make them pay) comment at Gandhi Maidan in Patna.

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, who was among the first to launch a sharp attack on the opposition, and especially at the reaction of former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, wrote on his blog that the Congress-led UPA had run a 'terrible' Government and an even 'more terrible' opposition. While Singh had sought to elevate himself to the status of a neutral third party, he had nonetheless raised doubts over India's right to defend its sovereignty. "I was most disappointed with a brief but highly objectionable statement of former PM Manmohan Singh," said Jaitley. Singh had said that he was disturbed with the "mad rush of mutual self-destruction" by the two nations, implying that Modi's decision was as much a rogue act as Pakistan's and that of its military-terror complex that had inflicted so many cuts and wounds on India over the decades.

On the evening of February 26th, Modi fielded the foreign secretary, rather than the three armed services chiefs or military officials, to detail the action taken by the air force. Officials Open spoke to contend that it was a calculated move to assert both globally and locally the contention of "non-military, pre- emptive action" against terror which would be in agreement with international convention on the lines of the US strike on Abbottabad to target Osama bin Laden in Pakistani territory. Soon after, Finance Minister Jaitley justified India's action in self-defence stating, "If the US could carry out operations using Navy SEALs in Abbottabad to kill Osama bin Laden in 2011, so can India."

THE SELF-DEFENCE narrative was soon echoed at key capitals around the globe. The US, France, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Iran and Russia, defended India's right to self-defence. Iran, among all of these nations, had lost several of its revolutionary guards to a horrific terror act emanating from Pakistani soil recently. Following Pulwama, Doval had talked to the US National Security Advisor John Bolton on February 15th. The two had agreed, at the time, that Pakistan should be held accountable, under UN resolutions, to remove all hurdles to designate JeM leader Masood Azhar a global terrorist. Bolton had also backed India's right to self-defence against cross-border terrorism and offered help in booking the terror outfit's architects. Post-Balakot, Doval also spoke with the US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman Al Saud also had a chat with Modi and offered support to India.

Things were tougher on the domestic front as national security has hardly been an attractive slogan in Indian elections historically. Unless, of course, when India went into a full-fledged war with Pakistan and liberated Bangladesh in 1971.

For obvious reasons, the opposition was unwilling to give the Prime Minister any credit for what transpired in the aftermath of Pulwama. They went on punching holes in every gain that the country appeared to have made on the global stage in isolating Pakistan and exposing it for nurturing terror factories that punctured India at will over the last few decades. TV channels in Pakistan went to town with the combined opposition statement that demanded that Modi should "not politicise" the Balakot air strikes. Worse, they questioned the Government's claims of damage inflicted in the operation. Jaitley urged the opposition to "grow up" instead of obstinately seeking to score a self-goal for the country. Congress leader Digvijay Singh, meanwhile, demanded that the Government release video proof of the damage inflicted, on the lines of what was done by the US after the Abbottabad Operation to take out Osama bin Laden in 2011. Others like Mamata Banerjee, West Bengal Chief Minister, chose to put their weight behind the Congress on this after a prestigious Australian institution claimed that not much damage appeared to have been inflicted based on conventional satellite images. The attacks on the Modi Government implied that the establishment had fabricated the extent of damage to capitalise on this politically in the run-up to the General Election. To that extent, it implied, the stated objective of the Modi Government had not been achieved. One senior Congress leader, Salman Khurshid, went to the extent of tweeting that Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman had earned his wings during the UPA rule in New Delhi.

On March 5th, Air Chief Dhanoa emphasised in a press conference that the IAF fighters had released a payload of 1,000 kg on the target. Putting a number to those killed in the strike, however, was the job of the political establishment, he said. On March 5th, Home Minister Rajnath Singh reiterated that 200 terrorists were killed at Balakot. Commenting on the questions over the numbers dead in the Balakot attack, former National Security Advisor Shiv Shankar Menon said in an interview to a news channel, "The numbers are really immaterial, whether it is 300 or 50 dead. I'm concerned with the outcomes." Menon added that the point was that the IAF was able to successfully conduct the air strikes on the JeM camp at Balakot and in doing so, sent out a strong message of warning against further terror strikes by Pakistan. However, it had to be followed up consistently by multiple overt and covert measures on the political, diplomatic, financial and other fronts, he stressed.

THE POLITICAL ATTACK ON Narendra Modi is being carried out along predictable lines. In the aftermath of the surgical strike following the terror attack at Uri, a section of Modi's critics had begun voicing doubts over the success of the operation. However, the Modi Government resisted the urge to use visuals of the surgical strike in the run up to the Uttar Pradesh elections in 2017. Post-Balakot, he is setting the agenda not just for the upcoming elections, but for the future of India's national security. On March 5th, Modi said at a public rally: "Na rukenge, na jhukenge" (we won't stop, we won't bend). And, "My opponents are busy striking at me. I believe in striking only at terrorists who harm this country." This election will not only revolve around Modi but will focus on his performance.

The Balakot air strike fits in with the slogan that the Prime Minister had himself spelt out at Gorakhpur in eastern Uttar Pradesh recently: 'Namumkin toh mumkin hai' (the impossible is now possible). That, by all insider accounts, is likely to be upgraded to 'Modi hai toh mumkin hai' (Modi makes it possible).

Also Read